Oh, dear. They put me on the spot. Statues and Slavery. If you’ve been following my Yale Trilogy, you’ll know that Part One, The Doubtful Diaries of Wicked Mistress Yale, is rooted around Elihu Yale’s involvement, on behalf of the English East India Company, in the Indian Ocean Slave Trade during the 1680s.

Elihu Yale – the Pub, the Person and Slavery

Now, we have a pub in the middle of Wrexham called the Elihu Yale. It’s a Weatherspoons pub. And a while back there’d been a petition going around requiring the company to change the name – a petition that sprang up, of course, from the Black Lives Matter protests. The name seems fairly appropriate to me, given the way the company’s owner, Tim Martin, treats his staff – but that’s a different matter entirely. Though, given the Yale books, I suppose it was fairly natural that I’d be asked for my views.

So my basic answer was to say, no, I don’t think there’s any overwhelming majority view in Wrexham the pub’s name needs changing. But is there a need to educate local folk a bit better about Elihu Yale’s dark side? Or to educate our kids better about the lasting evils of the slave trade? Oh, definitely.

Apologists for the Slave Trade

I suppose what’s surprised me most over the past few weeks has been to see a whole batch of posts that seemed to question the significance of the Atlantic Slave Trade and its current impact on today’s society. Almost apologists for the slave trade. Things like: ‘Well, this is just how civilisation was at that point, it’s what they did.’ Or: ‘Well, they were just men of their time.’ Or sheer nonsense, like: ‘Well, there were more whites taken as slaves to North Africa than blacks as slaves to the United States.’

The History of Slavery

It’s plainly true that most cultures have kept slaves throughout history – usually captives taken as prisoners of warfare or conquest, and almost always for the direct use of their captors. Slave labour, of course. But the European powers – and especially Britain – are unique in both the industrial scale of their slave trading and the way in which they used that trade to build much of their national economies. But it was never true that slavery was simply “just how civilisation was at that point.” Throughout history from the 16th century onwards there have been huge movements recognising that slavery was an evil – the various Quaker/Dissenter faiths in Europe and the USA. Or the steps taken by the Muslim Mughal Emperors to stop the trade in Indian slaves by the East India Company etc.

But it all prompted me to check out the consensus among historians specialising in comparative studies of the slave trade in the modern era (1500s onwards).

Slavery Data

The best data seems to show the following…

Crimean Khanate Slave Trade. Organised by Crimean Muslim Tatars. 1.5 million Russian, Polish and Lithuanian slaves between 1500 and 1700.

Barbary Slave Trade (so-called “White Slave Trade”). Organised by North African Arab raiders. Possibly 1 million European white Christians slaves from Spain, Italy, France, Britain etc between mid-1500s and mid-1800s.

Indian Ocean Slave Trade. Organised by English, Dutch and French East India Companies, plus Arab raiders. Possibly 1 million Indian, East African and Chinese slaves between mid-1600s and late-1700s.

Atlantic Slave Trade. Organised by Portuguese, British, Spanish, French, Dutch and Danish companies. A conservative 12 million African slaves between mid-1500s and mid-1800s.

There doesn’t seem to be a generally accepted figure for the probably incalculable numbers of First Nation American Indians taken into slavery. But this was also almost entirely by European colonists.

Worth noting, too, that current estimates put the numbers presently suffering enslavement, forced labour, at around 25 million. The highest proportion of those are women and young girls.

Slavery and Racism

But is slavery linked to racism – or, rather, to exploitation and the exercise of power? Well, of course, it’s all of those things. It’s a typical feature of slavery that those engaged in its practice generally seek their prey among people they consider to be racially (and/or gender-wise) inferior. So, that mindless “bred in the bone” hatred or fear or loathing of black folk, Asians, Jews etc. Maybe always, too, that added ingredient of misogyny towards women. Hence the quite correct Black Lives Matter link between racism and slavery. Between slavery and statues.

And pulling down statues? Statues and slavery? I had to admit if I’d been in Bristol on 8th June 2020 I would have been tempted to join the protestors pulling down Edward Colston’s statue. Tempted, but only that. Because I’d have known I was on a slippery slope. First, I’d give the Daily Mail an excuse to detract from the important message of the Black Lives Matter campaign. And, second, that I’d be giving a licence to the UK’s right-wing lunatics. The ability to claim they were exercising “the will of the people” by attacking statues of Mandela and Pankhurst.

Colston’s Statue

No, in the end I’d have fallen into the camp arguing that Colston’s statue should have been kept – though possibly shifted to a museum – with a decent plaque saying something like:

This statue was sculpted by Irish artist John Cassidy. It was erected in 1895 by the citizens of Bristol who, at that time, wished to commemorate the local philanthropy of Edwards Colston. However, that philanthropy amounted only to a tiny proportion of Colston’s personal wealth. And Colston’s wealth derived substantially from the Atlantic Slave Trade – his philanthropy driven entirely by his selective religious beliefs.

In fact, there have been various proposals to add a second plaque to the plinth to make Colston’s history clearer. The best of these said:

As a high official of the Royal African Company from 1680 to 1692, Edward Colston played an active role in the enslavement of over 84,000 Africans (including 12,000 children) of whom over 19,000 died en route to the Caribbean and America. Colston also invested in the Spanish slave trade and in slave-produced sugar. As Tory MP for Bristol (1710-1713), he defended the city’s ‘right’ to trade in enslaved Africans. Bristolians who did not subscribe to his religious and political beliefs were not permitted to benefit from his charities.

17th Century slave traders still alive and kicking in Bristol

The addition of such a plaque was blocked, however, both by Conservative councillors and, strangely, by the charity calling itself the Society of Merchant Venturers. That organisation may presently perform many charitable acts. But, in the 1690s, they campaigned for the Royal African Company’s slave trade monopoly, opened it up for all comers. It was thanks to this same Society of Merchant Venturers that the Atlantic Slave Trade proliferated to such an extent. 12 million African slaves!

So maybe that’s the story the papers didn’t bother to tell us about statues and slavery. That Colston’s statue isn’t some innocent piece of street furniture. That it stood in the heart of Bristol without any educational plaque. Because organisations like the unaccountable Society of Merchant Venturers continue, even today, to exert considerable influence in our society. They remain unwilling to be honest about their part in the slave trade, maybe even proud of it.

Racism alive and kicking in that particular chunk of the British Establishment. And racism very directly linked to the slave trade.

And now, a Liverpool solution!

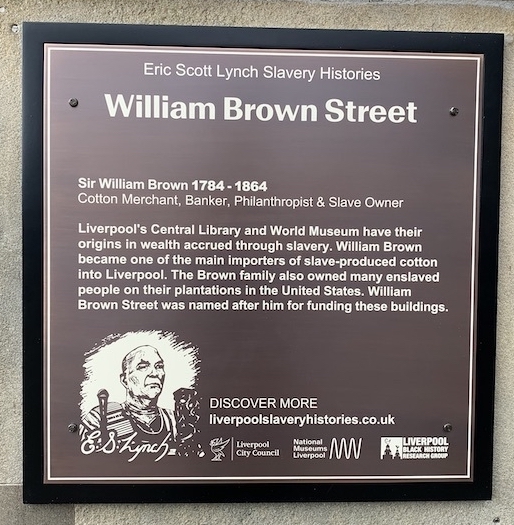

But Liverpool has now shown the way with a solution to this whole question of statues and slavery.

I had the great privilege of knowing Eric Scott Lynch, a well-known local Black historian, staunch trade unionist and Black community activist. From the late 1970s onwards, Eric began to organise his own slavery walking tours of the city, and these were eventually organised officially through Liverpool’s Maritime and Slavery Museum. Eric passed away in 2021 but, over the years, he was responsible for educating literally thousands of Merseysiders, tourists, school kids and older students about the facts and the evils of the Atlantic Slave Trade.

Meanwhile, another local historian, Laurence Westgaph, along with the Liverpool Black History Group and other supporters, campaigned successfully, over several years, for the various authorities to mount explanatory plaques in the city’s streets and locations associated with the slave trade. The first of those was erected on Tuesday 5th April 2022, in William Brown Street. The Eric Scott Lynch Slavery History plaques.

So, there – the answer to my problem. Now I won’t be put on the spot anymore. Should they change the name of the Elihu Yale pub in Wrexham? Should they change the name of Yale University in Connecticut (as their students so frequently demand) because their first benefactor and namesake had links to the Indian Slave Trade? Should Elihu’s fine tomb in the churchyard of St. Giles in Wrexham somehow be at risk because of those same links? Of course not. But perhaps wherever his name has prominence there should be a simple plaque, an explanatory plaque, so that we look up and see our history with eyes wide open.

I have no memory of Liverpool’s role at school – but if it was mentioned…it was done without emphasis. Merely as a part of Liverpool’s past with no opinion expressed…just accepted.

I had a coffee recently in a Café in Booker Avenue and noticed a picture of a huge liner. Thought why a picture of a ship? Then returning home checked Booker Avenue and discovered it was named after a Liverpool man from many years back. I love my city and really just accepted it without thinking of the past….wow – shocked, really shocked….this road named after a Slave Trader! In my education I had a knowledge of Liverpool and Bristol were two of the main ports, but did not linked them so much with the depth of our involvement in the Slave Trade. Was aware of slaves being sold here but it was only a few. Did some reading and wow they were. Yes it was a very profitable way to enrich so many! Then read that people that did – also became Lord Mayors so not just about profiting from the trade but also gaining in recognition from the City!

Horrified and thankful to the Lawrence Westogaph – thanks for your input on our city and it’s past.

It’s a good point. I don’t remember anybody teaching us about Liverpool’s own history when I was at school (in Bootle), either. As a kid, there were stories about slaves being chained up at the Pier Head but mostly nonsense and no context. I only really began to learn a lot more after I went on some union courses in the 1970s and then got to know the community in Toxteth during the 80s. And then I met Eric Lynch, the slave trail walks, the opening of the Slavery Museum – still, I think, one of Liverpool’s finest achievements. And the work goes on, as you say, thanks to folk like Laurence Westgaph – but many others besides. As more and more of the plaques go up, to explain the links between the city’s street names and other locations, I think we’ll all be a bit shocked by the exact number of people we remember by their names on statues, buildings, street corners – but usually without knowing the evil reason why we remember them!