Real-life Amado Granell plays a big part in A Betrayal of Heroes alongside our fictional Jack Telford – and readers have been asking for more about him. Well, here’s the full story…

In Alicante lives a man called Miguel Ángel Pérez Oca. He’s 77 now. A famous science teacher, writer and illustrator of books on astronomy and other subjects. Author of The Secret Life of Copernicus. I’ve never met him, but I owe him a great deal.

Why? Because in 1970 he married and, soon after, bought an electrical appliances shop on the city’s Avenida del Poeta Zorrilla. He bought the place from an older man – a man he described as circumspect, reserved but incredibly kind. It was many years later when Miguel Ángel discovered that the old shop owner was a hero of the Liberation of Paris, Amado Granell Mesado. And it was from Miguel Ángel’s blog that I first began to learn more about Granell’s extraordinary life.

From Burriana to Orihuela

Granell was born on 5th November 1898 in Burriana (Castellón), near Valencia. He was the son of a timber merchant and worked in the family business until the age of 22 when he enlisted for army to fight in the Rif Wars in Morocco. But his father denounced him because the legal age of adulthood was then 23. Deemed not to have parental consent, Amado was rejected for military service.

His father wanted him to remain with the business. But, instead, Amado trained as an electrician and began to work for the company Eléctrica Balaguer in Valencia. This company opened a shop in Orihuela (south of Alicante), on the Calle San Pascual, where he was transferred in 1927. Here he met Aurora Monzó, with whom he raised two daughters, Aurora and Amparo.

When Eléctrica Balaguer went bankrupt, Amado and his wife started their own store for electrical appliances. Bicycles and motorcycles. In Orihuela, of course, apparently on Calle Luis Barcala. During this time, he became interested in politics. He joined Izquierda Republicana, the mostly socialist Republican Left party. And he became a member of the (mostly socialist) union confederation, UGT.

Granell in the Spanish Civil War

In July 1936, a group of right-wing army generals, including Francisco Franco, launched the military coup. A coup against Spain’s elected Popular Front Republican government. And triggered the civil war. Amado, now 37, became a member of the Orihuela City Council and part of a recently created Anti-Fascist Liaison Committee. Its main task during those turbulent first days was to protect Orihuela’s works of sacred art. From the Colegio Santo Domingo and other churches before they were destroyed by extremists.

A couple of months later he resigned from his political position to enlist in the Republican army. Amado was assigned to a machine gun unit of the Iron Battalion, reaching the rank of second lieutenant. He took part in the fighting around Toledo and then in the Defence of Madrid, now as a captain in the Motorised Machine Gun Regiment. Then at Teruel during the winter of 1937-38. Later in 1938, as a major of the 49th Mixed Brigade in the failed defence of Castellón. Finally, at the beginning of 1939, the last heroic throw of the dice. At Fuente Ovejuna and the Battle of Valsequillo, initially successful for the Republicans but eventually won by the rebel troops.

At that time the war seemed already lost for the Republic and many soldiers began to desert. But Amado returned to Orihuela. He spent a few brief days with his family. Following the visit, his wife Aurora became pregnant with their third child, who would also be named Amado.

At the end of March, Granell went to Alicante with his brother Vicente, who had served as a policeman in Valencia. They both knew that certain death awaited them if they were captured by Franco’s rebel forces.

In search of a boat that would carry them into exile, both boarded the British tramp steamer, SS Stanbrook. Skippered by Archibald Dickson, the Stanbrook sailed from Alicante on 28th March 1939. She arrived in Oran the next day, carrying the very last group of Republicans into exile, around 2,000 of them.

Thanks to the efforts of his brother, who knew influential people in Oran, both initially escaped being sent to concentration camps. Unlike the vast majority of the other Stanbrook passengers. However, when Vichy France acquired control of Algeria, Granell ended up being taken to one of these forced labour camps.

North Africa

Details of his internment are sketchy. But it’s likely he was initially at Camp Morand, in Boghari, then transferred to the prison fortress at Bossuet. And, finally, after it was opened in March 1941, to the particularly evil camp in Djelfa. It was there that many of those who’d attempted escapes from other camps were consigned.

But wherever he’d been held he must have escaped again, or otherwise gained his freedom, by the autumn of 1942. We know this because, when the Americans invaded North Africa in November 1942 (Operation Torch), Granell was there. With the Free French Resistance, to help guide the Allied troops against key objectives in Oran.

Subsequently, Granell and other exiled Republicans enlisted in the African Free Corps of the French Army. He fought in the Tunisia Campaign in 1943. There he was wounded but promoted to the rank of lieutenant. Later, he transferred to the newly formed Second Armoured Division of General Leclerc’s Free French forces.

He carried his rank into the Ninth Company, Third Battalion of the Chad Motorised Infantry Regiment. Almost all the members of this company were also Spanish Republicans. It therefore quickly became known as La Nueve.

After training at Temara, and receiving American equipment and vehicles, the company shipped out from Oran on board the Franconia in April 1944. They were landed at Glasgow and sent by train to East Yorkshire, specifically to the village of Pocklington. More training, in preparation for the invasion of Europe. Though they did not arrive in Normandy until 1st August, almost two months after D-Day.

Normandy and Paris

Lieutenant Granell was now company adjutant, second in command to their French captain, Raymond Dronne. In that capacity he led his men through some ferocious fighting in Normandy. For example, in the battle at Écouché.

Later that same month, the Allies had fought their way to the outskirts of Paris. There was reluctance on the part of Eisenhower and Montgomery to enter the city itself. The German commander, von Choltitz, had orders to burn Paris to the ground. Liberating the city could have been a costly gamble in many ways.

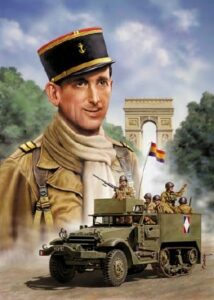

But then came news that the Resistance in Paris had risen against the Germans and the dice were cast. Leclerc’s Second Armoured Division had the primary task of advancing into the city centre. And though most of their units became bogged down in the attempt, on 24th August, one company managed to break through. It was La Nueve, with Dronne and Granell in command.

On the following day, they were heavily involved in the surrender of Paris by von Choltitz. And on 26th August, La Nueve took pride of place in de Gaulle’s triumphal procession down the Champs-Élysées to Notre Dame. The company’s half-tracks were emblazoned with the names of the battles in which they’d fought back in Spain. Guadalajara. Brunete. Teruel. Belchite. And so many others. In the world’s press, photos of Amado Granell and the leaders of the Resistance. The headline? “Ils sont arrives!” They have arrived.

Granell was now famous. De Gaulle offered to have him promoted to the rank of major if he became a French citizen. But Amado politely declined. All the same, he would later be decorated with the Croix de Guerre. Five commendations, as well. And, finally, with the Legion of Honour.

Lorraine and Alsace

Leclerc’s Division, the Chad Motorised Infantry Regiment, and La Nueve enjoyed only a few days respite. Then the advance into Lorraine and Alsace. Desperate fighting at Châtel-sur-Moselle, at Baccarat and elsewhere. Granell distinguishing himself yet again.

Finally, the liberation of Strasbourg in November 1944 and the fulfilment of Leclerc’s Oath of Kufra. It had been taken by the general’s men back in early 1941, deep in the Libyan desert. A promise not to lay down their arms until the French tricolore flew once more above Strasbourg Cathedral. An almost impossible dream. But a dream now become reality.

Granell, however, wasn’t at Strasbourg. By now, he was far from well. Exhaustion, blood poisoning, virus, all conspired to have him sent back to Paris. And there he remained until the end of the war, training new recruits.

La Nueve went on fighting, of course, all the way to the Eagle’s Nest at Berchtesgaden.

National Alliance of Democratic Forces (ANFD)

Meanwhile, Granell took part in a different set of adventures. An alliance of progressive Spanish Republicans was determined to make a fresh attempt at restoring democracy in Spain. It’s clear that many promises had been made by the Allies. Promises that, once Hitler and Mussolini were defeated, their attention would next turn to Spain and Franco.

But it was now plain that these promises wouldn’t be honoured. Therefore, this alliance of Republican socialists, exiled in France, sent delegations to the Spanish monarchists, exiled in Portugal. A united front. To seek a restoration of democracy with a constitutional monarchy. And one of the main Izquierda Republicana spokespersons in the negotiations? Amado Granell Mesado, the now famous hero from the Liberation of Paris.

After three years of discussion, though, the alliance fell apart. Juan de Borbón was more interested in his own royalist deal with Franco. Disillusioned, Amado settled in Paris for a while. He opened a restaurant, Los Amigos, on the Rue du Bouloi, which became a meeting point for Spanish Republicans.

Return to Spain

By now, Granell’s wife Aurora was living in Valencia with their three children. We know that, in 1948, his son Amado, now 19, and one of his daughters, Aurora, 22, travelled to Paris to meet him. By then there was a new love in Granell’s life. Marcelina Gaubeca was 32 years younger than him. But he would be with Lina until his death.

In the early 1960s, the couple finally returned to Spain. Santander. Barcelona. Madrid. Valencia. Granell probably used a false passport since an order for his arrest had been signed in his absence in 1940. Perhaps it was all made easier when, in 1964, Franco organised enormous celebrations. Twenty-five years of peace – though not for the countless victims of Francoist repression. Still, there was some notion of amnesty. And it’s possible the journeys of Amado and Lina were made easier this way.

One way or the other, in 1969 they were in Alicante. Running that electrical appliances shop which, a few years later, they would sell to Miguel Ángel Pérez Oca.

Sueca and Granell’s death

On 12th May 1972, Amado Granell died near Sueca, south of Valencia. A strange traffic accident while he was driving from Alicante to Valencia itself. A journey to the French consulate so he could sort out some documents relating to his French pension. On his tomb in the cemetery at Sueca there’s a marble slab, paid for by the French Government. An image of a silver palm branch and the letters L.H. for Legion of Honour.

Amado was 73 years old. He missed seeing the return of Spanish democracy, for which he’d fought so hard, by only three years.

Recovering the memories

In 2004, they held a commemorative event at his birthplace in Burriana. His daughter, Aurora Granell, and his granddaughter, attended – as well as his second compañera, Lina Gaubeca. It was thanks to Lina that Miguel Ángel Pérez Oca was to see and photograph Amado’s documents, possessions and medals.

In August 2014, in Paris, during the 70th anniversary celebrations of the city’s liberation, Amado’s daughter Aurora was there to speak about her father – then more famous in France, perhaps, than in Spain. Aurora was there again for the 75th anniversary in 2019.

Then, just a few years back, a young councillor in Orihuela, Karlos Bernabé Martínez, put forward a motion for Orihuela itself to celebrate the importance of Amado Granell’s life. And also to commemorate the anniversary of his death. To celebrate Amado’s life alongside that of Orihuela’s other great celebrity, the poet Miguel Hernández. That motion came to fruition in November 2021 when Orihuela organised two-weeks of events to commemorate Granell and to name one of the town’s squares in her honour, thanks to the persistence of another young councillor, María del Mar Ezcurra García.

When General Leclerc presented Amado with the Legion of Honour, he did so with these words: ‘If it’s true,’ he said, ‘that Napoleon created the Legion of Honour to reward the brave, nobody deserves this more than you.’

References for this blog: Cyril Garcia’s biography, Amado Granell, Libérateur de Paris; the piece by David Rubio for the website Alicantepedia; and, of course, the biography blog of Amado’s life by Miguel Ángel Pérez Oca for Alicante Vivo. In addition, Diego Gaspar Celaya’s book, Banda de Cosacos. Photos mainly courtesy of those two blog posts and the image of Granell’s tomb by Inner Circle readers Kelvin and Babs Ling.

Hi Dave, enjoyed reading the update and what a wonderful photo of Amados medals etc. Were you both still in Spain for the commemorations in Orijuela?

Burriana have also named a street in his honour, next time I pass that way I will take a photo.

Looking forward to the publishing of the new book.

Regards Kelvin and Babs.

Hi Kelvin. No, we were on our way back to Plague Island when the commemoration but when we’re back, in March, hoping to meet up with a couple of the councillors in Orihuela and take some snaps too. Stay safe. Dave and Ann

Dear Dave,

Unfortunately, your sources are bad.

I recommend that you read the following books, which are historical studies based on historical documents :

Banda de Cosacos, Diego Gaspar Celaya, Marcial Pons Historia

La Nueve, Cuadernos de historia militar, Desperta Ferro Ediciones

Pierre

Sources may not be complete, but bad because…? I’ve got Banda de Cosacos, but why does this add to the contents of the blog?