In The House on Hunter Street, the novel’s main protagonist, Cari Maddox, describes the state of the campaign for women’s votes in 1911 like this:

So many suffrage societies in Liverpool now, she couldn’t count them anymore. Forty different groups? Fifty? And most of them wouldn’t have spat on the others if they’d seen them on fire.

Fine, perhaps she exaggerated – but only a little. Everybody else had got together for the big rally on St. George’s Plateau last June, but the Women’s Social and Political Union stayed away – held their own event a few weeks later. And the movement no nearer working together than it had ever been. Yet those of them in the WSPU reserved their greatest scorn for the snooty mares in the Women’s Suffrage Society – regardless of everybody’s admiration for Eleanor Rathbone.

But how accurate is this picture? Were the divisions really so bad between the various groups we now lazily imagine as one single entity – the “suffragettes”? And was this simply a “Liverpool thing” or was the picture similar across Britain?

The Origins of the Campaign

Perhaps the first thing to remember is that the women’s suffrage campaigners didn’t spring from nowhere. In the later years of the 19th Century, many women were already involved in various campaigning activities through the political parties – Liberals, Conservatives, and the newly-formed Independent Labour Party – as well as religious, philanthropic and workplace organisations.

Just one example might be Jeannie Mole who eventually settled in Liverpool (96 Bold Street) with her second husband. Jeannie was instrumental in 1889 for establishing the Liverpool Workwomen’s Society, which later became the Liverpool Society for the Promotion of Women’s Trade Unions. She was heavily involved in the Liverpool Women’s Industrial Council, campaigns for women’s rights and several prominent disputes. Little wonder, then, that many of the activists involved as women trade unionists – women like Mary ‘Ma’ Bamber – should also play a central part in the fight for women to have the vote.

There’s a list in Krista Cowman’s superb book, Mrs Brown is a Man and a Brother: Women in Merseyside’s Political Organisations, 1890-1920. It’s a list of the organisations which played some part, within Merseyside, during that fight. Just a small sample includes: the Birkenhead Women’s Suffrage Society (BWSS); Catholic Women’s Suffrage Society (CWSS); Church League for Women’s Suffrage (CLWS); the Liverpool branch of the Conservative and Unionist Women’s Franchise Association (CUWFA); Liverpool Women’s Suffrage Society (LWSS) – part of the National Union of Women’s Suffrage Societies (NUWSS); Men’s League for Women’s Suffrage (MLWS); the United Suffragists; Votes for Women Fellowship (VFWF); Women’s Freedom League (WFL); Women’s Liberal Federation (WLF); the Women’s Social and Political Union (WSPU); and others.

And, by the way, for anybody wondering about the title of Krista Cowman’s book, you need look no further than one of Hunter Street’s real-life characters – dockers’ leader James Sexton. Sexton famously sang the praises of a married couple, the Browns, and their political activism. But he was so stumped for an adequate way to describe Mrs Brown’s attributes that he did, indeed, put her on the pedestal of being “a Man and a Brother.” Sexton would later talk about the stalwarts within a demonstration by the unemployed, saying, “the women were the best men.”

So, Cari Maddox was correct. Suffrage societies in Liverpool, across Merseyside, were many and varied. And women weren’t restricted to being affiliated with only one organisation.

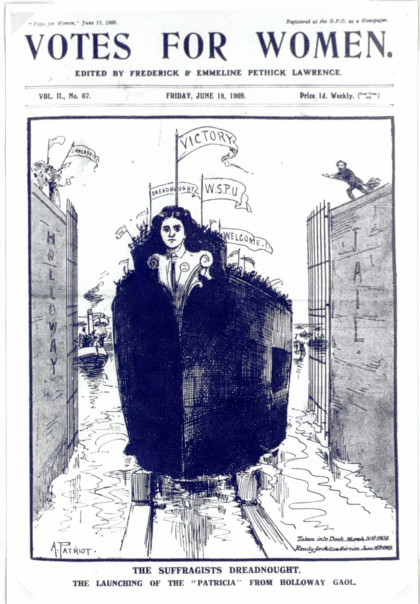

The real-life Patricia Woodlock – who also appears in the novel – had not only helped to establish the first branch of the Women’s Social and Political Union (WSPU) for Liverpool but was also hugely active in the city’s branch of the Catholic Women’s Suffrage Society. Patricia Woodlock was imprisoned seven times for her suffragette activities and suffered the longest prison sentence – three months in solitary confinement – as well as being subjected to force feeding.

And rivalry between the groups? Or outright animosity?

Suffragists v. Suffragettes

First, an important reminder about terminology.

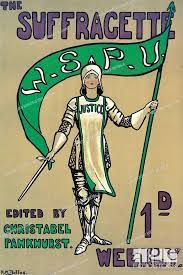

Until 1906, all those campaigning for women’s votes were generally described as suffragists. The largest of the suffragist organisations in Britain was the National Union of Women’s Suffrage Societies. But by 1903, Manchester-based Emmeline Pankhurst and others had decided that the NUWSS strategies were too staid. No progress was being made. More direct action was needed and, with her daughter Christabel, she formed the Women’s Social and Political Union. Their commitment to direct action – to “deeds not words” – caused Daily Mail reporter Charles Hands to attempt to belittle them, coining the phrase suffragettes. But for members of the WSPU it became a badge of honour. The non-militant members of the NUWSS continued to find favour in the press, while militant members of the WSPU continued to be reviled.

And hence the rivalry. Or, at least, in part. There were other issues as well, with the NUWSS being seen as essentially having middle and upper class members and leadership, while the WSPU was seen as being more welcoming to working class women – at least in the WSPU’s early years.

Indeed, even the terminology could be a source of conflict. Before too long, suffragists were being routinely described in the press as suffragettes and vice versa. Confusion in the minds of journalists, politicians and the public between the two groups. Many members of the NUWSS were quite bitter about the way that their meetings were broken up and they suffered violence at the hands of people who simply saw them all as suffragettes. Lucienne Boyce deals with this problem in detail in her piece about Welsh suffragist Winifred Coombe Tennant: https://www.lucienneboyce.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/L-Boyce-Winifred-Coombe-Tennant-Final-Website-version.pdf.

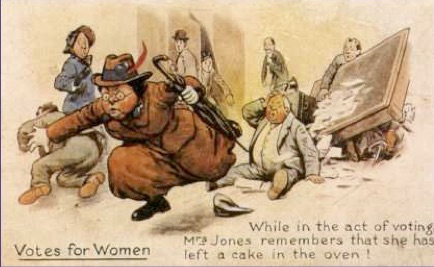

Opposition to Votes for Women

In addition to these “internal” divisions, suffragists and suffragettes alike suffered opposition – sometimes violent opposition – from anti-suffrage groups, like the Women’s National Anti-Suffrage League. More widely, votes for women were opposed – often for the most bizarre reasons – by all manner of politicians, church leaders, and aristocrats. Leading women, too, like novelist and social reformer Mary Ward. For them, a woman’s place was in the home. In the kitchen. A subservient role, as dictated by the Bible. Women couldn’t join the army, so how could they be equal? How could they have the intelligence to make political decisions?

This was a global issue, of course. Women’s suffrage movements were springing up everywhere, but by 1906 Finland was still the only country in the world to give all women (and all men) the right to vote. And it’s easy to forget that, in Britain, at the time when The House on Hunter Street is set (1911), the only men entitled to vote were “householders” over the age of 21.

I hope the novel does justice to some of these issues and pays proper tribute to the twenty Merseyside women who suffered imprisonment and the horrors of force feeding. As I’ve said elsewhere, for anybody who wants to find out far more about this topic, I’d highly recommend Krista Cowman’s book, as well as Marij van Helmond’s Votes for Women: the Events on Merseyside, 1870-1928 – which has a foreword by the indomitable Margaret Simey. In addition, for wider and wonderfully written coverage of the suffragette struggles, anything by the Bristol historian and exceptional novelist I’ve already mentioned, Lucienne Boyce: https://www.lucienneboyce.com.

But since The House on Hunter Street is set only in 1911, I guess we should finish with a few words about what happened next.

Success in the End

As delaying tactics by the Liberal government became more complex, attitudes and militancy within the WSPU hardened considerably. In 1913, Lloyd George’s house was bombed despite his support for women’s suffrage. In the same year, Asquith’s government passed the Prisoners (Temporary Discharge for Ill-Health) Act – also known as the Cat and Mouse Act – which allowed hunger-striking prisoners to be released when their health was at risk, only to be imprisoned again when it had improved! And in June 1913, Emily Davison was famously killed when she walked in front of the king’s horse during the Derby.

Then came the First World War. Emmeline Pankhurst suspended the WSPU’s campaigns. Emmeline and Christabel positively supported the war effort, even to the point of endorsing conscription. The NUWSS position was slightly different, encouraging its members towards voluntary war service work. Sylvia Pankhurst, on the other hand, remained implacably and correctly opposed to this most meaningless of wars. She helped to establish the Women’s Peace Army and the Workers’ Suffrage Federation.

In February 1918, the British government passed the Representation of the People Act. This gave the vote to women over the age of thirty, but only those who met certain property qualifications. About 8.4 million women gained the vote this way. But the Act also gave the vote to all men over the age of twenty-one. In a strange way, this simply replaced one inequality with another.

It would take another ten years of tough campaigning before, in 1928, the Equal Franchise Act gave the vote to all men and all women.

Leave a Reply