While doing some further research about the War Routes of Northern Spain – Franco’s propaganda strategy to bring in tourists while the conflict still raged – I came across an account of a Coventry school teacher (and Franco supporter), Miss Walker, “spreading the word” about the Nationalists’ side of the story to a meeting of her local Soroptimists’ Club. Here’s part of what she said:

“That night we spent in the Hotel Real at Santander, the summer resort of the Court. Espina’s last book records how 200 men were thrown alive with weights on their feet from the Lighthouse Rock, into the sea sheer below, by the enemy. Today a young soldier was playing with a child in the sunny doorway.”

She’d not long returned from one of those battlefield propaganda tours, the Rutas de Guerra, and she’s repeating the story told in fascist author Concha Espina’s Retaguardia, and presumably recounted for the tour group also by their Falangist guide as an illustration of the “Red Terror” – atrocities allegedly committed by the forces of the Republic. It’s an incident very typical of the “scripts” used by the tour guides and then repeated by the tourists themselves when they returned from their trips and spread the word about the importance of Franco’s “crusade.”

Later, this monument was erected to commemorate the Falangist martyrs in question. And, while I’ve been writing the first draft for my own modern guidebook to the War Route Tours, it’s highlighted again perhaps the most difficult aspect of the Spanish Civil War in most contexts – how to deal with the thorny question of this “Red Terror.”

Easy enough to write about the atrocities committed by Franco’s forces and Falangist death squads. There had been the instruction issued to supporters by one of the other rebel generals weeks before the military coup even began – an instruction “to eliminate left-wing elements, communists, anarchists, union members, etc.” And the slaughter committed by Franco went on long, long after the actual war itself had ended in 1939. The Popular Front Republican Government at least tried – though not always successfully – to end extra-judicial killings, whereas, for the Nationalists, they remained a matter of policy.

And indeed, these instructions were followed literally in the opening moments of the insurrection when rebel Moroccan troops in Melilla rounded up and executed innocent civilians. Word spread. It spread quickly. In areas where the coup was successful, like Navarra, Paul Preston (The Spanish Holocaust) reminds us that there was no Republican violence at all, but a substantiated figure of 3,280 people assassinated by the rebels.

Word spread further. And in areas where the coup had failed, like Asturias, Vizcaya and Cantabria – so, yes, in Santander – the authorities and individuals wreaked revenge on the right-wing supporters they thought responsible for the rebellion. Spanish Civil War correspondent John Langdon-Davies recounted that, yes, atrocities on both sides during the early part of the war. But these were largely “random” killings by terrified mobs.

And then, Paul Preston again, reminding us that in one German bombing raid on Santander alone, 47 women, 11 children and 9 men were killed, causing a “vengeful crowd” to kill 156 imprisoned army officers, right-wing militants and priests. Indeed, priests. Paul makes the point that a “focus on numbers of fatal victims… misses the wider issue of the daily violence of grinding poverty and social abuse.” And there was a clear understanding, first, that the Catholic Church and its priests were often apologists both for that poverty and social abuse and largely responsible for the rebellion itself. Images of priests sporting bandoliers of bullets and preaching insurrection from the pulpit – or standing at mass gravesides to bless the killers – were only ever going to put them in the same category as other political plotters and insurrectionists. And The Spanish Holocaust cites many, many testimonies (usually from Francoist supporters) of the rabid priests with blood on their own hands.

Later, Miss Walker talked about some of the War Route tour beyond Santander itself, further along the coast to the west. We’ve already mentioned Asturias – a beautiful region of Spain, with the highest ranges of European mountains apart from the Alps. These are her words:

“From Covadonga we went on to Oviedo, the martyred city. In the miners’ rebellion of 1934 the dynamiters had entered through a sacrist’s close to the lovely ninth century Cámara Santa and blown it up, leaving a great hole in the Cathedral roof.”

She doesn’t seem to have bothered saying much more about the events of 1934, but they are hugely relevant to the rest of the story of Spain’s civil war. Revolutionary strikes among Asturian miners soon turned to violence and armed conflict, and there’s no doubt that much of the violence against churches, priests, business men and supporters of the Falange was bloody and mindless. Over 100 members of the Guardia Civil and 33 clergymen were summarily executed, along with some other individuals. But then came the revenge. 20,000 Moroccan troops from the Army of Africa under the command of Franco and General Yagüe were unleashed against the miners. Hundreds of deaths occurred in the fighting on both sides but the eventual outcome was inevitable. In the repression which followed, an estimated 200 strikers were summarily executed but there were many more reported incidents of torture, rape and mutilation perpetrated by the Moroccan soldiers.

And, less than two years later, came the military coup – this time a rebellion led by generals like Franco and Yagüe. The images of 1934 on each side were powerful. For the right, the nightmare of armed workers exacting summary revenge on their old enemies. For the left, the sure knowledge of the savagery which would befall them in a repeat of the 1934 repression.

But in most of Asturias the coup was a failure. Except in two places – at the Simancas barracks in Gijón and in the city of Oviedo itself, defended by right-wing Colonel Antonio Aranda. Here’s starry-eyed Miss Walker again:

The story of the defence of Oviedo was told to us by one of the defenders – a ”Laureado.” The highest military order in Spain is the laurel wreath Cross of San Fernando.

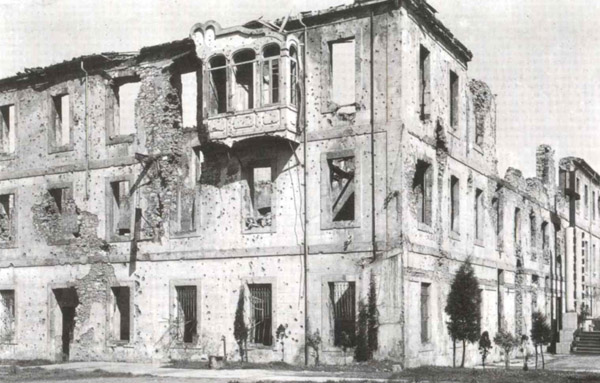

Of Oviedo’s 70,000 inhabitants, only 20,000 remain. Whole streets of houses are mere shells, the churches all destroyed, while the hospital received thousands of shells one night. The soldiers only ask you to admire the courage of the women and children who carried on.

She was once more a little short on detail. Both Oviedo and the Simancas barracks were besieged by workers’ militiamen, mostly miners again. But then rebel ships and bombers attacked civilian targets in the rest of the city, killing many innocent women and children. A militant anarchist mob took revenge, as at Santander, by executing right-wing prisoners including priests. The barracks was eventually overrun and the garrison killed.

And the other side of Oviedo’s story? Colonel Aranda had taken hundreds of “hostages” and many of these disappeared forever. Falangist death squads hunted down and slaughtered ‘leftists’. Prisoners were used as human shields. And then a rebel relief column marched towards Oviedo from Galicia. Terrible punishment was wreaked on Republican forces they encountered along the way.

The relief column arrived in Oviedo and lifted the siege in October 1936 and Paul Preston details the 370 prisoners immediately taken and executed without a trial. He goes on to set some further context to the violence.

“In the course of the war in Asturias,” he says, “around two thousand rightist prisoners were murdered. The rebels’ revenge when Asturias was occupied saw them kill nearly six thousand Republicans.”

And again, these killings by the rebels were very much “institutional.” But, of course, Miss Walker would not have been told any of that – and nor, I suspect, would she have cared very much. The reason that only 20,000 of Oviedo’s population remained in the city was that the rest had fled before the rebels’ advance, many of them remembering what had happened in 1934. By the time she arrived in the city late in 1938, according to Paul Preston’s research, perhaps as many as two thousand had been slaughtered there alone. And the irony? Preston records that “at least twenty schoolteachers were shot and many more were imprisoned.”

The institutionalised violence perpetrated by the Nationalists would, of course, go on and on. But Miss Walker – perhaps recalling the luxury of her room in Oviedo’s Nuevo Hotel Pasaje – finished her account on a cheerier note:

In earlier days it was said that the workers of Spain went hungry to bed every night. Today no one is hungry in National Spain; there is plenty of food, good and cheap, the bread the little ones had was the same quality as that served to us in the great hotel.

Of course, the victims of violence – right and left – in Oviedo, and elsewhere along Spain’s northern coast, may have had an entirely different view of things. And such violence inexcusable, regardless of which side the perpetrators may have been on? Of course. But that’s easy to write and say with hindsight, and from the perspective of my own comfortable life all these many years afterwards.

Brutal. Hard to reconcile with the wonderful nature of the Spanish people – the majority of them, anyhow – we know today. But that is war, humanity’s affliction.

I did my very best to discover what had happened later to Miss Walker but without much success. Only an account of a schoolteacher, now married, but with the maiden name Walker, who died in one of the many German bombing raids during the Coventry Blitz. The same person? I don’t know – but, if so, it would perhaps have been yet one more irony.

Leave a Reply