David Ebsworth’s second novel, The Assassin’s Mark, is a Christie-esque thriller set on a battlefield tour bus towards the end of the Spanish Civil War.

Propaganda in the Spanish Civil War

At the beginning of December 1938, Victoria Station, in London, saw the strange sight of an army returning from war. Thousands of people waited for the train from Newhaven and the disembarkation of 305 volunteers from the British Battalion of the International Brigade that had fought beside the people of Spain for the previous two years in their struggle against the Fascists under General Franco. There were flags and union banners galore, mounted police controlling the crowd. Yet, outside the station, were was a fair amount of consternation, a general public not quite sure what was happening. And, apart from left-wing newspapers like the Daily Worker, you would have searched in vain on the following morning for a headline mention of the event in the rest of the national press.

It was not that the Spanish Civil War had been entirely neglected by the media, but there was a certain ambivalence towards it all that was perhaps reflected in the way the returning heroes of the British Battalion were treated when they had landed in England after their particularly rough Channel crossing from Dieppe, their interrogation by Customs and Foreign Office officials, representatives of the Security Services. After all, these men had technically committed an illegal act by travelling to Spain in the first place. It was in contravention of the Non-Intervention Agreement, overseen by Britain, that was supposed to have maintained international neutrality in the conflict.

Indeed, the International Brigades had only been withdrawn by the legitimate government of the Spanish Republic in deference to that Agreement, a last desperate attempt to win foreign support for the war that was now, at the end of 1938, quickly slipping away from them. Yet the Nationalist army of rebel General Franco was still heavily supported by Hitler’s Luftwaffe, by regiments of Mussolini’s soldiers, by Italian submarines that continued to sink British shipping in the Mediterranean with total impunity. And the newspapers here in Britain barely mentioned these things. There was hardly a whimper about them from “the man in the street.”

So how had the propaganda campaign swung so heavily in Franco’s favour? Why so disastrously against the Spanish Government?

Franco had launched his military coup in July 1936, believing that he would have little difficulty overthrowing the Popular Front Republican Government, elected four months earlier. But he was wrong. Spain was divided, the government badly prepared, though workers’ militias sprang to the barricades of Madrid and elsewhere, determined that Franco would be stopped.

There was an early rash of atrocities committed by both factions, though the influence of the Catholic Church, both in Europe and the USA, ensured that the killing of priests by one side grabbed headlines, while the mass murder of socialists and union members by the other did not. The Church was less forthcoming, too, when Franco’s atrocities went on for at least the following nine years, probably accounting for an estimated 200,000 victims. And the Church was responsible, also, for spreading the threat of a “Red Menace” in Spain – since Russia was, after all, the only major power supporting the Republic. But this antipathy towards the Spanish Government was also obvious closer to home. The British establishment contained significant pro-Nazi elements – members of the royal family, prominent politicians, newspaper owners (typified by the Daily Mail’s support for Mosley’s Blackshirts. And while Britain was supposed to oversee the Non-Intervention Agreement, a blind eye had been turned entirely towards the massive German and Italian involvement in Spain – their “dress rehearsal” for the bigger conflict that they both knew would be coming, while Britain still toyed with appeasement.

There are parallels here, of course, with the other main news this week. The British establishment’s right-wing condemnation of the ANC in the early ’80s, their portrayal of that struggle as a “heathen Red menace” against “civilised Christianity” was a real echo of their attitude to that earlier conflict in Spain. And while it may be true that many of the International Brigade members were politically-motivated left-wing party activists, there were just as many who went to fight simply because they realised the threat posed to the world by rising Fascism – many Jews, for example, who knew very well what was already happening to their people in Germany.

In total, approximately 35,000 volunteers joined the International Brigades, coming from 53 different countries. They included 2,300 Britons, of whom 526 died in Spain. There were “celebrities” as well. Ernest Hemingway and Paul Robeson were just two of the famous folk supporting the Republican cause and helping to publicise it. But despite their efforts, it was somehow always Franco’s propaganda machine that gained the upper hand. It may seem inconceivable to us now, but even the German bombing of Guernica, with its eye-witness reports in the Times and other leading papers, was still covered by the majority of the world’s press from the viewpoint of Franco’s lies – that the town had instead been destroyed by Republican anarchists.

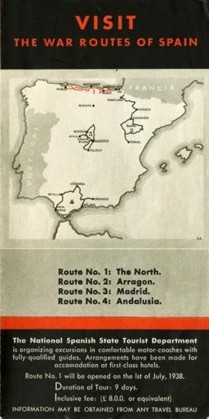

And Franco learned a huge lesson from the presence of “celebrities” behind the Republican lines. He developed an audacious plan by which, in the spring of 1938, he had not only set up a separate Nationalist Government based in Burgos, but had prioritised the establishment of a Tourism Department. Astonishingly, that Department was soon producing brochures inviting travellers to visit the battlefields of the North Coast on which Franco’s forces had so recently triumphed and despite the fact that the war was still very much in the balance. The first of these macabre tours took place on 1st July, 1938. At the end of the war, more routes were added, one in Aragón, another in Madrid, the fourth in Cataluña. Tourists arrived in large numbers – from Britain, Italy, Portugal, France, Germany – even some Australians. It is thought that there were around 42 tours in 1938 and 88 tours each year between 1939 and 1945. Estimates of participants vary between a minimum of 6,670 and a maximum of 20,010.

And Franco learned a huge lesson from the presence of “celebrities” behind the Republican lines. He developed an audacious plan by which, in the spring of 1938, he had not only set up a separate Nationalist Government based in Burgos, but had prioritised the establishment of a Tourism Department. Astonishingly, that Department was soon producing brochures inviting travellers to visit the battlefields of the North Coast on which Franco’s forces had so recently triumphed and despite the fact that the war was still very much in the balance. The first of these macabre tours took place on 1st July, 1938. At the end of the war, more routes were added, one in Aragón, another in Madrid, the fourth in Cataluña. Tourists arrived in large numbers – from Britain, Italy, Portugal, France, Germany – even some Australians. It is thought that there were around 42 tours in 1938 and 88 tours each year between 1939 and 1945. Estimates of participants vary between a minimum of 6,670 and a maximum of 20,010.

This previously untold story of Franco’s battlefield tourism forms the background to The Assassin’s Mark, a political thriller set on one of the tour buses and casts light on the Civil War, its propaganda, and the questionable role of Britain in the conflict, from the perspectives of the time rather than from hindsight.

At the same time, the sacrifice made by the volunteers is commemorated in the UK by the International Brigade Memorial Trust…

and, in the USA, by the Abraham Lincoln Brigade Association…

Let their memory also cast light on the darkness of Fascism and ensure that we never again allow its rise.

¡No Pasarán!

Read more about David Ebsworth’s second novel, The Assassin’s Mark

Read more about David Ebsworth’s second novel, The Assassin’s Mark

A Christie-esque thriller set on a battlefield tour bus towards the end of the Spanish Civil War.

Leave a Reply