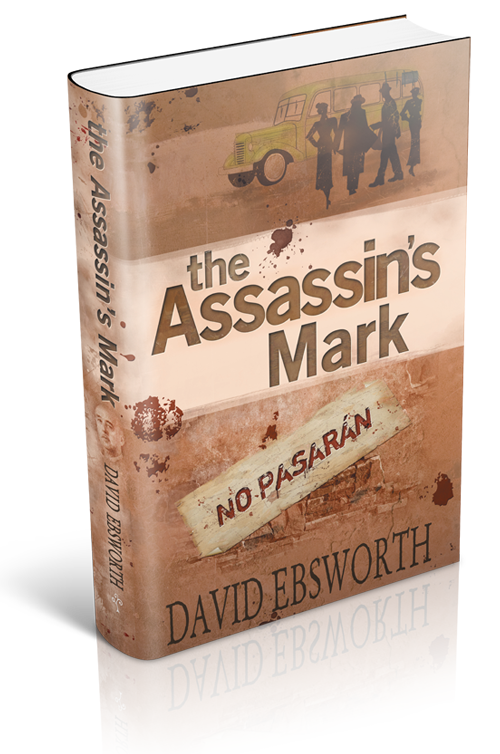

David Ebsworth’s second novel, The Assassin’s Mark, is a Christie-esque thriller set on a battlefield tour bus towards the end of the Spanish Civil War.

David Ebsworth’s second novel, The Assassin’s Mark, is a Christie-esque thriller set on a battlefield tour bus towards the end of the Spanish Civil War.

September 1938 – Spain’s Civil War has been raging for two years, the outcome still in the balance. But rebel General Francisco Franco is so confident of winning that he has opened up battlefield tourism along the country’s north coast.

Jack Telford, a left-wing reporter, finds himself among an eccentric group of tourists on one of the War Route’s yellow Chrysler buses. Driven by his passion for peace, Telford attempts to uncover the hidden truths beneath the conflict, despite the best efforts of the Caudillo‘s propaganda machine.

But Jack must contend first with his own gullibility, the tragic death of a fellow-passenger, capture by Republican guerrilleros, a final showdown at Spain’s most holy shrine and the possibility that he has been badly betrayed. Betrayed and in serious danger.

BUYING OPTIONS

The Assassin’s Mark has enjoyed some fabulous reviews since it’s publication in 2013, but it’s also now had its first formal literary criticism, from Brian Brown – sometime teacher, lifelong reader and literary critic. Here it is…

‘Everything’s a commodity these days’ comments a character at the start of this interesting take on a well-known murder/mystery genre set in the Spanish Civil War.

And as we join the story, we understand the macabre truth of this statement, as even while the brutal conflict rages, Franco’s regime organises battlefield tours for prurient onlookers.

Of course, public interest in war abroad is nothing new, it had been with us since the Crimean War and the dispatches of William Howard Russell. However, how public perception of conflict has been managed since the early 20th century and the rise of the hugely influential right-wing press is an entirely different thing, and in the years that preceded WW2, its role was one that makes reflection fairly uncomfortable.

Jack, a young left-wing journalist, finds himself in the company of a group of battlefield ‘tourists’ who broadly espouse the ‘strong and stable’ message that fascism from Mosley to Mussolini presented in the 1930s as a bulwark against Bolshevism.

There is much political polemic in the early chapters, but it is founded on a very clear and well-researched understanding of the complexities of the internal politics of Spain and how they related to those of Europe. The author manages to present a wide spectrum of how politics manipulate everything in time of conflict.

A favourite moment for me was the incident of the blind pianist who had ‘a certain talent for those sonatas and concertos favoured by dictators’, although in terms of misappropriation, it rather paled into insignificance next to the pilgrimage of the nuns around the battlefield.

As well as a well-versed political and historical account, many will enjoy the writerly element, with its nods to journalistic styles of the time and the ever-present Tolkien – a nice counterpoint there one feels – the ‘news’ largely ignoring the coming storm whilst the increasingly alarmed journalist reads Tolkien’s thinly-veiled allegory of what is about to engulf Europe.

But for all the portentous background, the trip does present us with a delightful comedy of errors enacted by the British, rather English, abroad with their pet obsessions ranging from food to sitting arrangements on the bus.

The accuracy and detail of the places visited in this perverse and grotesque pilgrimage really does bring the journey to life for the reader and for all the labels of a Christiesque novel, the reader does not find themselves turning the page to simply find the next victim. There is also much to read and reflect upon in the story’s portrayal of the shifting dynamics of the group and their emerging characters.

Interestingly, the latter part of the novel morphs into more of a political thriller as the group of sightseers fragment and the two main characters face their date with history.