Brief background to the Spanish Civil War

Spain had voted to become a Republic in 1931 and its royal family went into exile. But, outside its major cities, life in rural Spain was still feudal. Entirely controlled by the army, the catholic church and a handful of phenomenally wealthy landlords. Then, in February 1936, a left-wing Popular Front coalition was elected to power. It pledged to introduce reforms which were all anathema to those reactionary elements of the Spanish establishment. A plot was hatched by leading generals of Spain’s

army. And, on 17th-18th July 1936, they launched a military coup which, in turn, triggered a civil war. The rebel generals, including Francisco Franco, were eagerly supported by Hitler’s Germany. Germany readily dispatched most of its airforce to their assistance. And Mussolini’s Italy sent division after division of ground troops to supplement Franco’s forces.

Ranged against this “fascist clan” were those army units that had remained loyal to the Republic. Tanks and military advisors were sent to help the Republic by Stalin’s Russia. Various workers’ militias were formed. And 35,000 sympathetic volunteers from 54 different countries made up the republican army’s International Brigades. Three desperate years followed, and half a million people died in the conflict, either on the battlefield, or by execution, or in bombing raids. And in the aftermath of the war itself, it’s estimated that the victorious side – Franco’s Nationalists – was responsible for the execution of a further 100,000 Republican supporters or more, and the death of 35,000 more in concentration camps.

Strange Fact #1 – The Spanish Civil War began and ended with a Welshman

The success of the planned military coup depended heavily on the rebels being able to deploy Spain’s Army of Africa – based in Spanish Morocco – and this, in turn, depended on the leadership of its commander, General Francisco Franco.

But, early in July 1936, Franco had been posted to the Canary Isles and they needed a way to have him back in Morocco. So one of Franco’s advisers, Luis Bolín, hired Welshman Cecil Bebb to fly his DH89 Dragon Rapide all the way from Croydon to Morocco (Bebb was joined on the flight by Bolín himself, and also by British Intelligence officer, Major Hugh Pollard) and then await further orders. These he received, continued his flight to Las Palmas, where he collected Franco and delivered him to Tetuán early on 19th July so that the general could prepare his Moroccan troops for the invasion of mainland Spain, and join the uprising that had already begun there.

But, on the final day of the conflict, almost three years later, defeated Republican refugees

fled over the border into France in the north, or were funneled into the port of Alicante harbour in the south. Cardiff skipper Archibald Dickson – in direct contravention of the orders from his ship’s owners – ran the gauntlet of Italian submarines to carry a final desperate group of 1,835 (detailed in Dickson’s own report) from Alicante to relative freedom aboard his small cargo ship, SS Stanbrook. It was almost the last act of the war, and many thousands of republicans, left stranded on the quaysides of Alicante would soon be incarcerated in Franco’s concentration camps, or shot by his firing squads.

Strange Fact #2 – Madrid held out against a siege by Franco’s forces for the entire duration of the war

As the uprising began, on 18th July 1936, the Madrid army garrison at the Montaña barracks, supporting the coup, marched out onto the streets to take control of the city. But they were forced back by armed milicianos who eventually took the barracks and massacred many of the rebel soldiers. But Madrid then remained in Republican hands throughout the rest of the war despite being cut off from most of the rest of the country from August 1936 onwards. And despite the efforts of Franco’s “Fifth Column” – the many thousands of nationalist supporters trapped, along with the defenders, inside

Madrid itself. In November 1936, Franco’s forces launched a major attack, which succeeded in forcing its way into Madrid’s university complex. But, after bitter fighting, they got no further. 5,000 died on each side during the November fighting alone. Two major offensives by the rebels then attempted to entirely isolate the city. First, through the Jarama Valley in February 1937. And then through Guadalajara in March 1937 – though both of them failed to meet their objectives. Similarly, a Republican attempt to break the siege, at Brunete in July 1937, also ended in stalemate.

Beyond that, Madrid was bombed and shelled on a daily basis until, with the war effectively over, and after infighting on the Republican side, Franco’s forces finally marched into the city on 28th March 1939. The siege became famous for the slogan coined by the Spanish Communist Party’s Dolores Ibárruri, La Pasionaria. “¡No Pasarán!” They shall not pass! And, effectively, they didn’t, not until the war was over! The Battle for Madrid was, essentially, the first occasion that European fascism – the combined forces of Franco, Hitler and Mussolini – was stopped in its tracks.

Strange Fact #3 – Franco used Battlefield Tourism as an effective propaganda tool

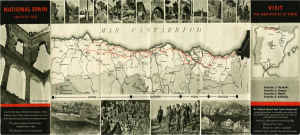

Early in 1938, Franco established an alternative Spanish Government, a nationalist government, based in Burgos, in northern Spain. He quickly introduced his own currency, the Burgos peseta. And soon afterwards, astonishingly, a National Tourist Department. Through his friend, Luis Bolín, this tourist department was soon producing brochures entitled, National Spain Invites You To Visit The War Routes of Spain. Brochures were circulated in various languages to all the major travel agencies of Europe.

The plan was to use the tours as a propaganda tour, to spin the nationalists’ side of the story to anybody prepared to pay the £8 cost of the one-week excursion. Within weeks, they were inundated with potential punters and the first tour took place on 1st July 1938. 42 of these tours took place throughout the rest of 1938. Then an average of 88 tours in each year between 1939 and 1945. Estimates for the total number of participants vary between 6,670 and 20,000.

Strange Fact #4 – Franco waged a separate war on the children of Republican families – and it continued until very recently

During the war itself, Franco used prison camps specifically for thousands of children, taken from

Republican families so they could be “re-educated.” Between 1939 and 1953, Franco’s regime officially used adoptions or care homes to forcibly remove 30,000 children from “leftist” families. After 1953, this official policy was dropped. But, by that time, the practice was so well-established that doctors, nuns and nurses continued to profit by selling tens of thousands more into adoption. Peter Anderson (Leeds University) and Montserrat Armengon have published research that shows this practice continuing well into the 1990s. An illicit trade for doctors and nuns, with as many as 300,000 children in total being “sold” for adoption.

Strange Fact #5 – Britain’s own Establishment played a particularly dirty game during the conflict

Apart from the involvement of British pilot, Cecil Bebb, in helping Franco reach his forces in Morocco to launch the coup – and Bebb accompanied by British Intelligence officer Major Hugh Pollard, of course – the British Establishment’s role in the Spanish Civil War is at least questionable. We colluded in the decision not to hold a meeting of the international Non-Intervention Committee until September 1936. By that time the Nationalists had received all the help they needed from Hitler’s Germany and Mussolini’s

Italy.

We allowed Franco’s representatives access to the British telephone exchange in Gibraltar so that they could successfully launch the coup.

Our government allowed Franco’s Army of Africa to be airlifted through British air space over Gibraltar.

We took no action when arms-related minerals from British companies in Spain (Rio Tinto, etc) were sequestered and sent instead to Germany. This was Franco’s reward to Hitler for Germany’s involvement.

Our government turned a blind eye to the 27 British ships attacked by Franco’s Italian u-boats and bombers during the conflict. 11 vessels were sunk. Then, to add insult to injury, the British Government decided to officially recognize Franco’s rebels many weeks before the war itself was concluded. Thankfully, Britain’s reputation in Spain has been “saved” by the sacrifices made by British volunteers in the International Brigades. And by the role played by heroic individuals like skipper Archibald Dickson.

You can learn far more about these generally untold stories, and much more besides, at my “Five Things” presentations in libraries and bookshops. Just get in touch if you’d like to organise one locally.

Picture of “Madrid Militiawoman” is actuallyof a civilian press liaison worker on the roof of party HQ on the Placa Catalunya in Barcelona. Didn’t really bother reading the rest because if you can misidentify such an iconic picture then perhaps the rest of your research can’t be up to much.

Bugger! Thanks for pointing this out, Bob. In fact, the caption was right but I’d uploaded the wrong image. Corrected now. Not so much a research issue as a proofreading slip. But you’re right, I should have spotted this before pressing the “publish” button.