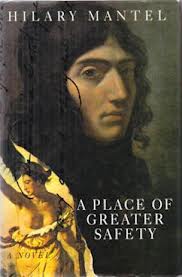

I’d read A Place of Greater Safety a couple of years after it was first published in 1992 and, at that time, I’d never heard of Hilary Mantel. Seems strange now, but that’s the way it was! In fact, it was recommended to me as a political novel, rather than a work of historical fiction and, of course, the book fits neatly into both genres.

I’d read A Place of Greater Safety a couple of years after it was first published in 1992 and, at that time, I’d never heard of Hilary Mantel. Seems strange now, but that’s the way it was! In fact, it was recommended to me as a political novel, rather than a work of historical fiction and, of course, the book fits neatly into both genres.

I hadn’t really visited the French Revolution since school days, thirty years earlier and, to be honest, I hadn’t understood it very well, even then. In fact, I picked up the book with some trepidation because my abiding memory of the subject was confusion. Yet I fervently hoped that Mantel would not dumb down the complexities of the period but, rather, might walk me all the way from those heady days in the run-up to July 1789; on, through the glorious declarations of the Rights of Man and the Constitution; to the revolutionary wars and their backlash; then the execution of Louis XVI; and, finally, through the Reign of Terror and the further upheavals of 1794.

I wasn’t disappointed, and I loved every one of my edition’s 872 pages.

But, more recently, I became aware my views were not shared by all of the book’s readers. No big surprise. Mantel has her own unique style, and it simply doesn’t suit everybody. I do hate it, however, when folk transpose their personal dislikes into criticisms of the writer or the writing. So I felt obliged to go back and read it all over again. And, once more, it didn’t disappoint me.

Basically, the book follows the fortunes of three main protagonists of the Revolution – Camille Desmoulins, Georges Danton and Maximilien Robespierre. She draws them in a way that will be familiar to later readers of Wolf Hall. Lots of dialogue. Their inner musings. The way that they are seen by each other. The ways they interact with their families and the vividly imagined women who share their lives. The sometimes tortuous manner in which the sweep of events touches them. The swirling host of minor characters among whom they swim. Confusing? For some, perhaps. But, for me, a masterpiece.

Back in the mid-90s, reading A Place of Greater Safety caused me to go off and pick up the best non-fictions I could find on the French Revolution – Simon Schama’s Citizens, and several others. That, for me, is the great thing about historical novels. To generate deeper interest. And, naturally, a study of those more academic works exposed the normal “factual” errors. But, to be fair, Mantel explains in her author’s note how and why she has sometimes simplified things for us. And then she gives us this wonderful advice, which will strike a chord with most historical fiction authors. “The reader may ask,” she says, “how to tell fact from fiction. A rough guide: anything that seems particularly unlikely is probably true.”

Leave a Reply