I remember plainly how I first stumbled across Alfred Neobard Palmer. I was writing the final part of my Yale Trilogy and was searching for significant events which might have taken place in Wrexham during 1715.

This search led me to a book with the lengthy title, A History of the Older NonConformity of Wrexham and its Neighbourhood, being the Third Part of a History of the Town and Parish of Wrexham. And the book led me to the chapter about the Sacheverell riots which shook Wrexham throughout 1715 itself. The book was published in 1888 – and written, of course, by A.N. Palmer.

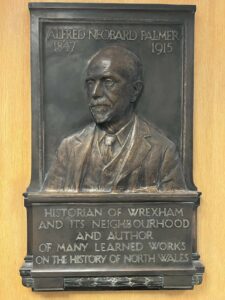

A few years later and I was working on our Wrexham history guidebook, Wrexham Revealed, and found myself returning time and time again to Palmer’s original research, still one of the key go-to sources for anybody researching Wrexham’s fascinating past. Indeed, I’ve never been able to find very much written about Wrexham’s history before Palmer came along. But there, in the archives section of Wrexham Museum (named for Palmer) was this bas-relief plaque…

…the man himself, in his later years – and the plaque had once graced Wrexham’s Library where, according to legend, visiting children were taught to rub Palmer’s nose for luck. Fair enough, given how prolific a writer he’d been.

Eight volumes written during his lifetime, the first published in 1885, and a ninth published long after his death. Before these, in 1883, a pamphlet entitled, The Towns, Fields and Folk of Wrexham in the Time of James the First.

But when I subsequently waxed lyrical about Palmer, I realised that other than among a handful of Wrexham’s current and dedicated historians, he seems to be entirely forgotten.

So, when I was thinking about writing a Victorian Wrexham crime novel – which eventually became Blood Among The Threads – I thought about Palmer yet again. The book was going to be set in 1876, against the background of the town’s great Art Treasures Exhibition.

But I also wanted to bring Palmer into the story – maybe bring him once again to a wider audience. Bring him out of the shadows, so to speak.

The obvious problem was that Palmer only settled in Wrexham in 1880. Four years too late for the story! But then I began to wonder “what if?” What if there was some logical reason he might have at least visited the town in 1876 itself? And there may just have been such a reason.

But let’s go back a step.

Wrexham’s later historian (Arthur Herbert Dodd (1891-1975) sets out the record from which we know most about Palmer’s early life. Born in Thetford on 10th July 1847, the son of a coach builder. His mother’s maiden name, Neobard, gifted to baby Alfred – in a very continental fashion – as his middle name. From 1855-60 he attended the local grammar school and, from 1860-62, the private academy of Independent minister Morgan Lloyd.

Dodd also provides evidence of Palmer’s religious beliefs. Brought up as a Primitive Methodist – one who follows the original teachings of John Wesley – he seemingly joined the Unitarians in 1873, his convictions causing him to permanently shun identifying himself with any “Trinitarian” forms of Christianity. Yes, I know, it’s complicated – but Palmer was basically a devout believer in God, a man filled with humility, “with a strong and compelling conscience, combined with broad charity and an acute critical judgement.” He had, therefore, been an ardent lay preacher in his youth.

He also served as a pupil teacher before being articled in 1863 to a druggist in Bury St. Edmunds. Then grants for research into pharmaceuticals, which led him to an appointment as an analytical chemist to a firm in Manchester in October1874 – which may (or may not) have been Levinstein’s dye-making business. By that time, back in Thetford, in January 1871, Alfred’s sister Katherine had died of consumption.

Manchester was on the one hand bad for Palmer’s health – he seems to have suffered permanently with chest problems – but good for him romantically. For, in Manchester, he met the daughter of City Surveyor John Francis. Francis, originally from Caernarvonshire, was a pillar of Manchester’s substantial Welsh community and patron to the Welsh bard “Ceiriog” – John Hughes, from the Ceiriog Valley and sometimes known as the Welsh Robert Burns.

On the 1871 Census, widower John Francis (61) is listed as living in Portland Crescent, Chorlton-on-Medlock, with his nine children and a servant, Ellen Welch. The youngest child, William, is 8 years old, so the mother must have died in the mid-1860s.

It’s unclear how Palmer met young Esther Francis (born 26 July 1856) – seemingly known to the world as Ettie. In the summer of 1876, Palmer would be 29, and Ettie just 20. Two years later, on 17th June 1878, they married, in Salford. The account of the marriage, carried in the Bury & Suffolk Standard, records that, by then, John Francis had already passed away. Similarly, on 5th March, Palmer’s mother had died in Thetford.

Might they both have been in Wrexham in 1876? Well, we don’t know. But it’s at least possible that John Francis would have been there – at the National Eisteddfod in August, the first ever held in Wrexham. John “Ceiriog” Hughes would have performed there. Would John Francis have missed the opportunity? Unlikely. And if Mr Francis travelled there from Manchester, why not his daughter Ettie? Why not Palmer? Pure speculation.

Arthur Herbert Dodd picks up the story at the point where, now married, Palmer and Ettie returned to Thetford – Manchester’s poisonous atmosphere simply being too much for Palmer’s health. Apparently, Palmer also made a trip to London, where he met a Wrexham man who offered him a post at his new enterprise – which Palmer accepted and moved to Wrexham in September 1880, working as an analytical chemist for the Zoedone Mineral Water Company.

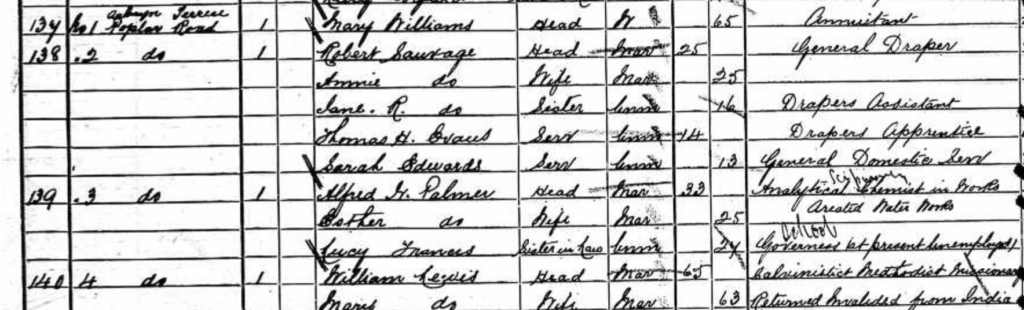

The 1881 Census confirms this, showing Palmer and Ettie living with her sister in Poplar Road, number 3 Arbryn Terrace. Lucy Francis is 27, a school governess, presently unemployed.

It seems that Zoedone (the trade mark for The New Aerated Beverage & Buffet Company Limited, or the Indian Zoedone Company Limited) owned several factories, one of which they’d just taken over from James Fisher Edisbury. Zoedone’s aerated products were bottled by Carter & Co of Bristol. The factory get a mention in the Wrexham Advertiser, in relation to Tuesday 18th April 1882, when they lowered their flags to half-mast to mark one of the biggest funerals Wrexham had ever seen – the funeral of Peter Walker, owner of the town’s Willow Brewery and a significant member of the community. But Zoedone itself was destined to go into liquidation in 1884.

Either just before or just after this, Palmer was appointed as chief chemist for the Brymbo Steelworks Company. Around the same time, in 1883, he’d written the pamphlet I mentioned earlier – The Towns, Fields and Folk of Wrexham in the Time of James the First. He’d written the paper for the Wrexham Scientific and Literary Society, and Dodd tells us that this “indicated the emergence of an interest which had simmered in his mind since as a youth, when he had talked with the Thetford local antiquary and pondered over the puzzle of detached portions of townships, in one of which he lived.” In other words, an interest in local history – and now the history of his adopted new home.

In 1885, a published essay, The History of Ancient Tenures of Land in the Marches of North Wales,

By 1886, he had left Brymbo – once again, apparently due to ill-health – and opened his own private practice as an analytical chemist, based in Chester Street, just across the road from the Baptist Chapel. In 1886 also, he publishedThe History of the Parish Church of Wrexham. And then, in 1888,The History of the Older Nonconformity of Wrexham.

The 1891 Census shows Palmer and Ettie living at the Chester Street premises (34a) with a domestic servant, Ruth Powell. But also in 1891, Palmer took up employment at the Cambrian Leather Works, where he remained until 1904.

In 1892, Palmer launched a campaign for Wrexham to have its own museum, writing to the Free Library Committee to install an antiquities case within the library as a first step. Some time later, the Wrexham Advertiser carried a piece in which Palmer was described as “the driving force behind the idea of setting up a museum”. It would, of course, be another 100 years before the campaign came to fruition.

In 1897, he published a less-than-successful novel, Owen Tanat. In fact, Dodd insists, each of his books became a drain on Palmer’s finances, although these were eased somewhat by family legacies in 1892 and 1894.

By 1900, he had completed The History of the Thirteen [Country] Townships of the Old Parish of Wrexham.

In 1901, they’re living at 17 Bersham Road, the house called “Inglenook”.

According to Dodd, Palmer’s finances were eased again in 1904 and 1908 by him receiving a Civil List pension, awarded to persons who, among other things, have made useful discoveries in science and attainments in literature and the arts, and therefore have merited the gracious gratitude of their monarch. Palmer had been nominated by his friend Edward Owen (1853-1943) – journalist, barrister and antiquarian, born at Menai Bridge.

In 1905, Palmer published A History of the Old Parish of Gresford and, subsequently, The Town of Holt in County Denbigh.

In 1910, in conjunction with Edward Owen, came their revised version of The History of Ancient Tenures of Land in the Marches of North Wales.

He had also begun work on The History of the Parish of Ruabon but this remained unfinished when he died, at “Inglenook”, on 7th March 1915. By that time, he had inspected most of the ancient monuments of Denbighshire and Flintshire, and played an active part in the excavation of the Roman site at Holt.

In honour of his work, in 1915, the University of Liverpool had determined to award him an honorary degree, but Palmer had sadly died before he could receive it.

The previous winter had seen him suffer from attacks of influenza, which later developed into pneumonia and then pleurisy. His estate amounted to £1976 11s 9d, divided between Ettie and Edward Owen.

Ettie lived on, at “Inglenook”, until her own death on 24th February 1929. She was buried three days later with her husband. The couple had no children, and only a blue plaque on the Bersham Road house remains to mark their time there. The house stands immediately across from the northern gates of Wrexham Cemetery, where the Palmers’ fine tombstone can be found. Sadly, there seems to be no permanent arrangement for keeping the tomb in good condition.

But here’s hoping that this may change. Here’s hoping, also, that the bas-relief plaque commemorating Palmer may, at some stage, have a more public location than with the Wrexham Museum archives department. And here’s hoping that my modest series of Wrexham Victorian crime novels may help to bring Alfred Neobard Palmer to a wider audience. Maybe – just maybe – when, in future, folk are asked to name Wrexham’s most celebrated citizens, Palmer will spring more readily to mind.

Leave a Reply