Spare a thought for poor Catherine Yale!

Elihu Yale, Welsh nabob, East India Company merchant adventurer, collector, philanthropist – and slave trader – gave his name to one of the world’s most famous universities. His biography has been written many times, most notably by the American academic, explorer and politician Hiram Bingham. Bingham is also generally credited with the discovery of Machu Picchu. Yet Yale’s biographers have consistently paid scant regard to his wife, Catherine, who was married to him for 41 years.

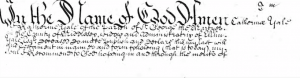

If poor Catherine gets a mention at all, it’s because of Yale’s last will and testament in which he most notably wrote: To my wicked wife… and then left a very large blank, not even giving the poor woman her name. Yet, with a modest amount of research, Catherine’s story turns out to be at least as intriguing as Elihu’s own tale.

So, this is what I think we know about her from the available evidence.

Catherine’s Background

She was born Catherine Elford in 1651, the daughter of Walter and Anne Elford. Her father was a Levant and Turkey merchant who had traded for some time in Smyrna. And, later, possibly in Alicante. Indeed, from the dates, Catherine may have been born there. But she certainly grew up in London, where Walter Elford had acquired a coffee-house. Anne Elford, Catherine’s mother, was the daughter of Richard Chambers, a former Alderman of London.

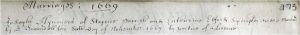

On 6th November 1669, at St. Botolph’s Church, Aldgate, Catherine married Joseph Hynmers, probably ten years her senior. He was the son of Richard Hynmers of Slimon, Devon, and had already been to India twice by the time they wed, and was now scheduled to return there, this time for the East India Company. Catherine and Joseph sailed together for the Company’s outpost at Fort St. George, at Madras – then a relatively small village on the Coromandel Coast.

Joseph’s position was an important one, Second to the Governor, and they enjoyed a comfortable house with several Gentue servants in Middle Gate Street. Catherine gave birth to their first child, Joseph Junior, in 1670; then to Richard in 1672; Elford in 1676; and Benjamin in 1678. Although even this is uncertain, for Joseph’s will, dated 1678, lists only Richard, Joseph and Benjamin as his sons – so it’s possible that Elford was actually the youngest.

The journey to and from Madras was a hazardous one, at least six months at sea and often much longer. But mortality rates at Fort St. George were high too, forcing her to send her boys home when she felt them old enough – usually by the time they were ten. It is possible, just possible, that she may have given birth to another child around 1674, though I’ve not been able to verify this.

Then, in 1680, after a prolonged fever, Joseph Hynmers died and left her a considerable fortune. He bequeathed sums of money to the oldest three boys but not the youngest – since he had written his will before Benjamin was born. But Joseph was buried in a fine mausoleum, beneath a tall pyramid that still stands in modern Chennai.

A Second Marriage

Within six months of Joseph’s death, however, Catherine had married again, this time to Elihu Yale. Yale had gone out to Madras as a clerk for the East India Company in 1672 and in 1680 he still held a relatively junior position. But over the next few years he had invested the wealth gained from his marriage to become a very prominent trader in his own right and, eventually, Governor and President of Fort St. George – now the centre of an astonishingly expanded Madras.

Yale’s family moved to the American colonies seeking religious tolerance and Elihu was born at Boston in 1649. They returned to England in 1652 and, by the time Elihu joined the East India Company, they were living at one of the family’s ancestral properties, at Plas Grono, Wrexham. Just about all of the Hynmers, Elford and Yale families were merchant adventurers and Catherine must have been immersed in this nomadic international community too.

Now married to Yale, and her eldest boys sent back to England, she began a second family – David Yale born in 1684; Katherine in 1685; Anne in 1687; and Ursula, probably in 1689. Tragically, little David died at the age of three and is buried in the same mausoleum with Joseph Hynmers, at Chennai.

A Return to England

In 1689, Catherine returned to England with her girls and one Gentue (Hindu) servant. Her boys were already with her mother. Things were not going well for Catherine at Fort St. George and we know that, by then, Elihu was sharing a second home with a Portuguese woman called Jeronima de Paiva, with whom he had another son, Carlos Almanza. It’s likely that he was also having a further illicit relationship with a woman (and business partner) called Katherine Nicks.

We know little of Catherine’s life back in London, but she certainly settled in the parish of St. Peter-le-Peor, around Broad Street, and soon her eldest son, Joseph Junior had also joined the East India Company and sailed for Madras, following in his father’s footsteps. Elihu Yale’s father, David Yale, died at Plas Grono on 18th January 1691, as did Elihu’s brother – also called David – on 26th January. Catherine’s own father, Walter Elford, died that same year and was buried at St. Edmund the King, Lombard Street.

Around 1697, Catherine’s second son Richard died, probably abroad and, soon afterwards she lost her mother too. Anne Elford was buried with her husband at St. Edmund the King, London. In the following year, Elihu’s other brother, Thomas died early October 1698. He had previously been with Yale in India. David Yale senior’s sister, Anne Hopkins died on 14th December 1698 and was buried three days later. Elihu’s mother died and was buried on 11th February 1698/9.

The Parish Registers (Denbighshire Archives) show that the Yales, along with Anne Hopkins, were all buried at St. Giles in Wrexham. The Hiram Bingham biography claims that Elihu’s father and mother, at least, are buried beneath the church floor, and presumably the rest of the family too.

Meanwhile, Elihu himself had come under suspicion from the East India Company’s Directors, accused of various financial irregularities and even the murder of three witnesses against him. He was replaced as Governor while the investigations took place and though the charges against him had all been dropped by 1696, his days at Fort St. George were clearly numbered.

He sailed back to England, along with his huge personal wealth, in 1699. Aboard the same vessel was John Nicks, Katherine Nicks’s husband, plus her four youngest children – those that, according to legend, had actually been sired by Elihu. Personally I think this is unlikely but we know that, when John Nicks returned to Madras, the children remained, in boarding school and pretty much at Elihu’s expense.

An Unhappy Marriage

From the time of his return to London, Elihu kept up a steady flow of correspondence with Katherine Nicks in Madras (over fifty letters during the following eight years) and from these we know that he bought a house in Austin Friars to accommodate his family – so, back with Catherine, though it seems this did not last long. He was soon dividing his time between a new property in London (Queen Square) and Plas Grono in Wrexham, and had established himself as a notable collector in sales of the exotic goods he’d brought back from India.

The letters also tell us something of Yale’s relationships. Fifty letters, all of them written in the few weeks at the end of each year before the window of wind and tide that allowed the East India Company’s vessels to sail for India. Six or seven letters written each winter, sometimes the content repeated and posted aboard different ships to make sure that at least some of them would arrive safely.

Nothing openly amorous, naturally, but certainly full of affection whenever they were not dealing with business. Glowing accounts of the love Yale bore for the Nicks children, scarcely a word about his own. Not a single mention of his wife by name, even though Katherine Nicks and Catherine Yale were well acquainted in Madras. And oh, the complaints. About his life in England generally, but in particular about the court cases against him.

Litigation

Catherine’s remaining sons began their own law suit against him. They claimed that they should have been entitled to a larger share of their father’s inheritance. And the youngest son, Benjamin, claimed he had never received any of the inheritance due to him through his mother’s marriage settlement with Elihu. The cases would rumble on for many years.

The usual biographies refer to tragedy striking again in 1704 when news arrived that Joseph Junior had died in Madras. But this is plainly incorrect. The Marine Records of the English East India Company and the Fort St. George Consultation Book show Joseph (having recently served as the Company’s Provisional Mintmaster at Madras) on the passenger list for the homeward bound Neptune, sailing for England on Friday 14th October 1699.

He would therefore have been back in England by mid-1700. In late 1702, Joseph writes from Portsmouth to Doctor Sir Hans Sloane – at that time Britain’s leading physician but also Secretary to the Royal Society – confirming that he has received the packets entrusted to him by the good doctor, presumably for onward shipment to Batavia (Jakarta). In January 1703 he gets a mention in the papers of Captain Thomas Bowrey.

Joseph had written to Bowrey from Portsmouth and was due to sail for Batavia as a supercargo on board the Todington. He had agreed to collect information on coins, weights and measures and customs duties on Bowrey’s behalf. Bowrey plainly knows the family very well and his business partner is Henry Alford – or could this have been Elford? On 10th July 1705, an associate of Bowrey’s meets Joseph (Hinmers) in Batavia, but he is about to leave. Joseph’s final destination is unknown but possibly Amoy (Xiamen) in China. The trail soon goes cold but it’s likely that Catherine would have received news of Joseph’s death in mid/late 1706.

The biographies, however, are usually equally careless about Yale’s money-lending practices and, most notably, in the case of Josiah Edisbury, Yale’s neighbour in Wrexham, and the man who originally built the fine mansion there known as Erddig Hall. The poor man needed a loan to complete furnishing of the house but Yale called in the loan at an extortionate rate of interest. It bankrupted Edisbury.

Society Weddings

In 1706, Catherine and Elihu’s daughter Katherine married Sir Dudley North, Member of Parliament for Thetford. Sir Dudley was cousin to Lord North and Grey, a gallant officer who had lost a hand at Blenheim in the service of Queen Anne but, on Anne’s death, became a staunch supporter of the Jacobite ‘Old Pretender’ James Francis Edward Stuart. Lord North and Grey was subsequently imprisoned for his alleged part in various Jacobite schemes and rebellions.

In 1707, the first of Catherine’s many grandchildren (Dudley North Junior) was born, but yet another of her sons – Elford – also died, again, probably abroad as a merchant adventurer.

Catherine herself was now just 56 and at least four of her sons – David, Walter, Joseph and Elford – were already dead.

On 6th July 1708, their second daughter, Anne Yale, married Lord James Cavendish, younger brother of the 2nd Duke of Devonshire. Lord James leased his property, Latimer House in Buckinghamshire – then still the original Tudor House – to Catherine, where she lived for the rest of her life, along with her own youngest son, Benjamin, and her youngest daughter, Ursula.

In 1711, the courts finally decided that Benjamin Hynmers (Catherine’s youngest son) was owed £8765. 18s. 10d, as the portion from the estate of Joseph Hynmers owed to him by Elihu Yale. Payment was made through Hoare’s Bank. The current value of that settlement is about £1 million.

In the following year, news arrived that the illegitimate son of Elihu Yale and Jeronima de Paiva, Carlos Almanza, had died in Cape Town. By that time, the other alleged mistress, Katherine Nicks, had also died in Madras. But her daughter, Ursula (named for Elihu’s mother) would, in 1719, marry the lawyer Sir Edward Betenson. And Betenson, for many years, pursued a legal claim against Catherine for a portion of Elihu Yale’s estate.

A record of the tombs and monuments in the grounds of St. Mary’s Church at Fort St. George recorded the death of Katherine Nicks. Here lyeth the body of Katherine Nicks, the wife of John Nicks, some time of Council of this place, who departed this life the 9th of December 1709: also five of her children, John, Isabella, Sibella, Catherine and Mary. Close by, the stone of John Nicks, who died on 14th March 1710/11 and another of their daughters, Anne.

A Widow Again

Elihu himself died in 1721, having earlier made many philanthropic donations. One of those went to a college in New Haven Connecticut. He was not the biggest donor, however. That honour fell to a gentleman called Charles Dummer. But, on balance, the governing body of the establishment felt that “Yale College” had a better ring to it than the alternative.

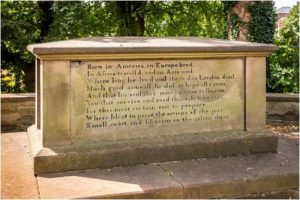

Elihu was buried, along with his parents and brothers, at St. Giles in Wrexham, where his own tomb still stands.

It’s a famous landmark inscribed with an equally famous poem. The Bingham biography gives some evidence that the version we see today was probably penned by Yale himself. Possibly with blanks left for family members to fill in the place of his death. This is how it reads now:

Born in America, in Europe bred

In Africa travell’d and in Asia wed

Where long he liv’d and thriv’d; In London dead

Much good, some ill, he did; so hope all’s even

And that his soul thro’ mercy’s gone to Heaven

You that survive and read this tale, take care

For this most certain exit to prepare

Where blest in peace, the actions of the just

Smell sweet and blossom in the silent dust.

But this is a version restored and repaired (and perhaps amended) by the Yale Corporation between 1874 and 1894. And the oldest recorded version, in 1778, records different final lines, as follows:

You that survive and read this tale, take care

For this most certain exit to prepare

For only the actions of the just

Smell sweet and blossom in the silent dust.

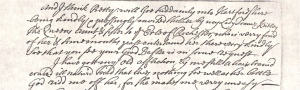

He left behind him too, of course, that last will and testament: To my wicked wife… Nothing! Why? Had she supported her sons’ Chancery Court claim against him? Or is there a clue in one of those letters to Katherine Nicks? One of the only references, it seems by the context, to his wife. “I have got my old affliction by me, a hair-brain’d crazed ill-natur’d toad that loves nothing so well as her bottle. God rid me of her, for she makes me very uneasy.” Is this Catherine? It seems likely. And, addicted to her bottle? If so, it is more probable that she might have suffered from that curse afflicting her class of woman far more than alcohol, the curse of laudanum – though that is pure speculation on my part.

The will, of course, was never signed and the probate battle therefore raged for some while. It is possible to date the will, broadly, from those named in its pages and then crossed out again after their own deaths, or those added towards the end. But Yale had obviously written it some years before his death. And this leaves open the question about why he did not finally sign the document when he fell ill.

Catherine’s youngest daughter, Ursula, also died in 1721, at Latimer. Catherine now remained with her son Benjamin until her own death on 8th February 1727/8. She seems to have spent her last years in and out of the courts. She was either defending herself in the Betenson claim or pursuing her own claims to recover outstanding debts owed to her late husband. Catherine and Ursula were both buried at the Latimer House church.

Ursula’s headstone still lies next to the church door and reads as follows:

Under this stone lies the body of Ursula Yale the third and youngest daughter of Elihu Yale the sometime Governor of Fort St. George in India. She departed this life the 11th August 1721 in the 36th year of her age. Eminent for many virtues particularly her charity in which she excelled. And at her death shew’d the same by a very liberal donation to the poor.

Lady Anne Cavendish was named as executor of Catherine’s will. Though when Anne herself died in 1734 this duty passed to her step-brother Benjamin. The will itself was signed and dated the day before Catherine’s death. It allows for the settlement of her debts and funeral expenses. An additional bequest of £5,000 to Benjamin. This in addition to the £10,000 she has already bestowed upon him. And there are several lines in which she stresses her special affection and natural love for her “most dutiful and obedient child.”

Then bequests to her daughter Lady Anne Cavendish (100 guineas); her grandchildren William and Eizabeth Cavendish (20 guineas each); the grandchildren Dudley and Anne North – their mother Katherine North had also died by then (20 guineas each; to her sons-in-law; her brother Richard (20 guineas each); significant amounts to other members of the family – including annual annuities to her widowed sister-in-law and a couple of maidservants; £50 to David Yale, Elihu’s nephew back in Connecticut; and an long list of smaller amounts to others. In total, the bequests – including that £10,000 already gifted to Benjamin – amount to over £17,000 – a sum that, according to Bank of England inflation calculators, would now amount to about £3.4 million.

Benjamin lived on at Latimer, cared for by his faithful servant, Mary Hall, until his death in October 1743. Benjamin’s own bequests helped to repair and “beautify” the church at Latimer. He’s buried there, and left a legacy of silver altar plate and chalices as well. He also left behind a charitable fund. This provided bread for the poor of the parish whenever they took communion. Wine as well, to be used for the communion itself.

He had been a great “subscriber” for new books too (an early form of crowd funding) so had his name listed as a financial contributor to various publications: A Complete History of Drugs, a translation from the original French work by Pomet (1712); Historical Collections of Private Passages of State by Rushworth (1721); Bishop Burnet’s History of His Own Time (1724); The Annals of the Reformation and Establishment of Religion, Volume One (Strype, 1725); and Sermons on Several Occasions, Volume One (1731) among others. A devout and learned man.

Benjamin was originally buried in a white marble altar tomb outside the farther end of the original church. Into the marble they’d carved an image of Benjamin’s head, weeping cherubs and a coat-of-arms. Under the monument was a vault and, in the vault, lead coffins – Benjamin’s, obviously, and almost certainly Catherine’s. When the church was effectively re-built in 1841, the new south wall of the south transept divided the vault. This effectively sealed off Catherine’s burial place.

Next to Ursula’s headstone is a more damaged memorial stone that reads:

In memory of good men being required to encourage the exercise of duty and honor in succeeding generations that it may be known that here lie the remains of Benjamin Hynmers Esq.

The rest of the inscription is difficult to decipher but talks about: his sincerity, integrity, innocence of manner and his benevolence, distinguished by a firm attachment to the constitution of the kingdom, church and state.

The dedication contains the names of Jonathan Wood and William Hall gentleman, probably his executors – William Hall being the brother to Benjamin’s “faithful servant” Mary Hall. In addition, there is mention of his mother, Catherine Yale. William inherited portraits of Catherine and her daughters, Katherine and Anne, though the later history of these paintings is a mystery. Similarly, we have no idea what happened to Benjamin’s white marble tomb.

Despite the number of grandchildren to Catherine and Elihu Yale, their line now seems to have vanished into history. No direct descendants still surviving.

Fascinating! Thanks for the painstaking research which allows us a glimpse into Catherine’s world. I will definitely have to visit St Giles’ and Erddig.

Thanks Jude. Glad you liked it.

Thank you so much for that research. I am conducting a One-Name Study of ‘Elford’ and this fills in some blanks I had on Catherine Elford. Very interesting!

Hey Liz. Thanks for getting in touch. I’ve not done any later research on the Elfords but an interesting family. Can you trace yourself back to Catherine and have you found out anything else yourself? If you want to chat by e-mail I’m… davemccall@davidebsworth.org. I’ve been doing lots of library and bookstore talks about the factual background to the highly fictionalised trilogy – and lots of interest in Catherine. Best regards and have a great Christmas.

I enjoyed reading this as I descend from Elihu Yale’s uncle Thomas Yale born at Plas Grono in 1616. He remained in Connecticut and his line continues to this day with multiple branches with one common ancestor. David, Ann and Thomas Yale were the children of Thomas Yale and Ann Lloyd Yale Eaton. They arrived in America in 1637. Thomas remains in Connecticut but David moved first to Boston where Elihu was born and then back to England. The senior line of the Yale family died out with the death of Sarah Yale. In 1821.

The Yale family in America continued to pursue opportunities merchants, manufacturing, engineering, and politics. An interesting family history to be sure.

Thanks Theresa and glad you enjoyed it.