Yes, building a realistic setting for our historical fiction can be fun. But recreating the world of Sixth Century post-Roman Britain in The Song-Sayer’s Lament had some real challenges.

Normally, I’d always start with maps for the period, to get the geography right. But I have this “thing” about language and authenticity, like this…

1. Sixth Century Language and Literature

I wanted The Song-Sayer’s Lament to have an authentic 6th Century “feel”, but I was writing the story, in modern English – and English therefore stands for the Brythonic language, variations of which would have been spoken in that period by all those disparate but related clans, which most certainly did not think of themselves as “British” or “Welsh” or “Celtic”, but as separate peoples, tribes, linked (or possibly divided) by a common speech – the Cousins’ Tongue, as I have called it.

And, because English substitutes here for that Cousins’ Tongue, it was important for me to make sure that place names, nicknames and individuals’ titles should convey in English those images that their original Brythonic names might have conjured up. In other words, I specifically chose not to use some form of pseudo-Welsh, for example, in place names – or, even worse, pseudo-Latin.

Welsh is a beautiful, lyrical but highly descriptive language, the rich simplicity of which would be totally lost for English-only readers who simply found themselves coming across locations like Gwynedd or Dinerth without knowing that these words convey something like the White-Wilds or Bear Fort respectively.

In my story, the religious orders of non-Christian Britons are the Oak Seers – my anglicised version of Middle Welsh dryw, Latin druidae, Modern Welsh derw, etc, etc. The Oak Seers have various sub-groups, with differing responsibilities, and among those are the Song-Sayers – those responsible for keeping the old lore alive through their verbal records, their poetry.

For my inadequate attempts to mimic some of the cadences that my Song-Sayers may have used, I went to the www.kernewegva site (A Guide to Welsh, Cornish and Breton Verse) and, whilst I’m not aware of any actual “Welsh” creation story surviving, I borrowed heavily from those Celtic tales told variously at www.historyarchive.whitetree.ca (Celtic Creation Story) and www.educationscotland.gov.uk (Celtic Creation Myth). I credited the resultant Song of the Great Melody to a fictional Tugri Iron-Brow, a potentially more realistic etymology of Taliesin. Here’s how it begins:

Hear now my tale of time before time. An endless sea’s Great Rhyme. Melody’s threads, creation’s chime.

I worked out the forms by researching Early Medieval “Welsh” poetry, verse structures, rhythmic and rhyme patterns, etc. I picked three different patterns that I could use easily, one for Morgose the Song-Sayer, one for Tugri Iron-Brow, and one for other poets. So Morgose, for example, was able to sing The Lay of Lir – a legend/memory of how the ancients first discovered the lands they called the Isles of Fair Presence, the name that the early Greeks and Romans may have heard as Prydain and corrupted into Britannia.

rhyme patterns, etc. I picked three different patterns that I could use easily, one for Morgose the Song-Sayer, one for Tugri Iron-Brow, and one for other poets. So Morgose, for example, was able to sing The Lay of Lir – a legend/memory of how the ancients first discovered the lands they called the Isles of Fair Presence, the name that the early Greeks and Romans may have heard as Prydain and corrupted into Britannia.

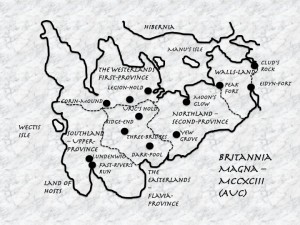

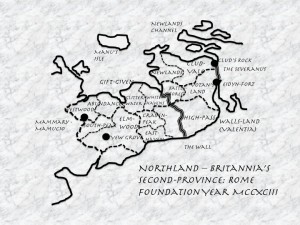

2. The Map of Sixth Century Post-Roman Britain

Once I knew where I was going with the language, I could start to think about the maps, the geography – and, of course, now equipped to provide meaningful modern English names which might decently reflect the images their original names might have conveyed.

The book therefore includes some interesting maps, showing the way in which my Sixth Century, “Dark Age” characters may have thought about the lands in which they lived. First, the region that they call Westerlands, those former tribal lands, which the Romans had called First Province, Britannia Prima…

Second, the area of Westerlands where the novel begins, in the White-Wilds, which we’ll later know as Gwynedd…

Third, each of the five former Provinces of Roman Britannia, now barely even recognised as distinct territories…

Fourth, the areas of Northland (formerly the Roman Province of Britannia Secunda) and Walls-Land (the former Province of Valentia), where some of the later action happens…

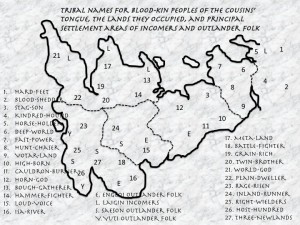

Fifth, a map showing my imagined spread of the various old tribal groups who, in 540 AD, still see themselves as distinct blood-kin, despite 400 years of Roman occupation. The map also shows the areas occupied by larger groups of Incomers (Irish) and Outlanders (Angles, Saxons and Jutes)…

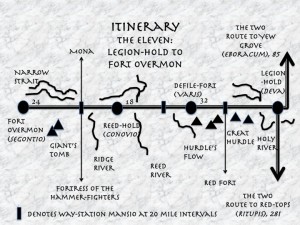

And, finally, a map showing the way that “road maps” would have worked at the time – itineraries, in common use until the 18th Century, with highways shown as straight lines, with principal settlements, distances and a few other significant details…

The maps are just a small part of the way in which we tried to faithfully recreate the way Sixth Century post-Roman Britain may have been in reality. But judge for yourself by reading The Song-Sayer’s Lament.

3. Populating the Maps

A growing number of websites lay out for us a superficially impressive chronology of events and genealogies for the history of post-Roman Britain. But I will ask readers to disregard them.

A growing number of websites lay out for us a superficially impressive chronology of events and genealogies for the history of post-Roman Britain. But I will ask readers to disregard them.

In truth, there are so few verifiable ‘facts’ for the two hundred years from 400 AD onwards that, apart from the archaeology, we have no real basis for recreating a true picture of the period.

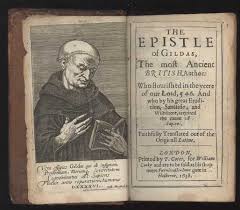

These are “Dark Ages” due more to our lack of knowledge than any floundering of civilisation and, for me, that darkness is only made worse by those who use the suspect and contradictory sources still available to us. Gildas, a monk living in the Sixth Century, wrote a treatise called On the Ruin and Conquest of Britain, which is short on detail and is, in any case, a self-confessed piece of religious propaganda seeking to demonstrate that the “downfall” of Britain at the hands of the Anglo-Saxons was God’s punishment for the sinful lifestyle of the Britons themselves. Contrary to popular belief, he mentions nobody called “Arthur” – even though, if Arthur ever existed, he is assumed to have been a contemporary of Gildas. Then comes The History of the Britons, written by another monk, Nennius, though not until 300 years later, around 830 AD. Nennius certainly refers frequently to “Arthur” – as a Dux Bellorum, or Warlord, rather than a king. But there is little detail and certainly nothing that cross-references with Gildas, for example. At least a hundred years later again, in the Tenth Century, we have the Annales Cambriae, which translates as the Annals of Wales. That sounds promising, except that this is a relatively modern title for a hotchpotch of documents, most of which are later still. And, again, none of the dates or events are consistent and, worse still, many of the documents come in several different versions.

There is good reason for the inconsistency of dates, of course. Good and simple too. Because there was no single calendar system in place at the time to which any of these “records” relate. The “Anno Domini” of the Julian and Gregorian calendars with which we are now familiar did not come into common use until much later, in the Ninth Century, so scholars of the time were trying to set the chronology of previous events according to haphazard reference points, such as “the thirteenth year of Justinian” or “the third year of Pope Vigilius” – all of which are, themselves, open to interpretation.

There is good reason for the inconsistency of dates, of course. Good and simple too. Because there was no single calendar system in place at the time to which any of these “records” relate. The “Anno Domini” of the Julian and Gregorian calendars with which we are now familiar did not come into common use until much later, in the Ninth Century, so scholars of the time were trying to set the chronology of previous events according to haphazard reference points, such as “the thirteenth year of Justinian” or “the third year of Pope Vigilius” – all of which are, themselves, open to interpretation.

Some of the post-Roman and Arthurian websites then seek to use Dark Age literature, rather than the chronicles, to shed light on the period – and particularly the Y Gododdin, which may have been written at the start of the Seventh Century by a northern poet-prince called Aneirin. The poem contains the Old Welsh half line bei ef arthur, variously translated as “he was an Arthur”; or “he was no Arthur”; or “he blamed Arthur”; or even one assertion that the word arthur is not a name at all but, rather, an obscure noun.

There is no doubt, however, that the name Arthur appears in later literary manuscripts – those that are now frequently described as The Four Ancient Books of Wales. The documents are written in a form of Welsh and date from the Thirteenth to Fifteenth Centuries, but contain copies and versions of texts that may have been set down originally in the Sixth or Seventh Centuries. But that means 800 years of copying errors, fashion and culture changes, political and religious tampering, literary adaptation, or simple grapevine misinterpretations that make The Black Book of Camarthen, The Book of Aneirin, The Red Book of Hergest and The Book of Taliesin priceless as historical artefacts but entirely unreliable as historical sources for the period. As that excellent author, Richard Denning, has put it: “Yes they are mostly poems and semi-myth. Indeed they are confusing and difficult to read, but for the historian and for the historical fiction writer of the post-Roman period, for whom the expression “beggars can’t be choosers” might have been invented, they give us something to get our teeth into and extract something approaching a history.”

I agree – at least in part. For those writing about the early Anglo-Saxon era of the late Sixth Century onwards, all of the manuscripts detailed above may indeed provide something upon which to bite. But for those writing about the hundred preceding years, and about the very uncertain fate of the Romano-British population, they hold little of real value.

Worse, they may have set us on an enormous wild goose-chase, certainly so far as names and genealogies are concerned. For example, it took me some time to realise that many of the names with which we are familiar for the period may be no more than titles or pseudonyms. The first part of Cuneglasus/Cynglas (or its variants), for example, seems to be equally capable of translation as dog, hound, lord, warrior or slayer, while the second part could be grey, blue, sky or red-orange – hence my use of Skyhound, Red Slayer, etc. Vortigern, a familiar character in tales of the period, isn’t a name at all. It’s a title. High Lord, or similar. Similarly, it is no wonder that we seem to have the name Gwenhwyfar (Guinevere) crop up so many times, since it is a descriptive title, broadly along the lines of a Pale/White Enchantress. I therefore decided to give my characters “real” names and settle the vexed question of Arthur by giving him a name that the bishops who recorded the period would not have wanted to repeat – Ambros, which signifies Divine.

Worse, they may have set us on an enormous wild goose-chase, certainly so far as names and genealogies are concerned. For example, it took me some time to realise that many of the names with which we are familiar for the period may be no more than titles or pseudonyms. The first part of Cuneglasus/Cynglas (or its variants), for example, seems to be equally capable of translation as dog, hound, lord, warrior or slayer, while the second part could be grey, blue, sky or red-orange – hence my use of Skyhound, Red Slayer, etc. Vortigern, a familiar character in tales of the period, isn’t a name at all. It’s a title. High Lord, or similar. Similarly, it is no wonder that we seem to have the name Gwenhwyfar (Guinevere) crop up so many times, since it is a descriptive title, broadly along the lines of a Pale/White Enchantress. I therefore decided to give my characters “real” names and settle the vexed question of Arthur by giving him a name that the bishops who recorded the period would not have wanted to repeat – Ambros, which signifies Divine.

And there’s another “wild goose-chase” about the name. It’s this. That there are no references to the name Arth or Arthur in Britain during the 6th Century but, by the 7th Century and later, it appears ever more frequently. So, the argument goes, there must have been somebody really well-known by that name who therefore popularised it. Yet we all know that this isn’t the only way for names to spread. And there is a very good alternative explanation. For the name Art, Arth, or Airt may not have been very common in Britain, but it was certainly popular in Ireland. The Fenian Cycle of Irish mythology (set in the 4th Century onwards) is filled with characters of that name. And, in the 6th Century, wave after wave of settlers arrived in western Britain from Ireland itself, brought their legends and their names with them, of course.

So I will ask readers to to join me on a journey. To a land that has nothing whatsoever to do with Geoffrey of Monmouth, or Chrétien de Troyes, or Mark Twain, or Tennyson. A land that owes far more to the Mabinogion than the well-intentioned attempts by some of my favourite modern novelists to interpret the classical romance tradition into more realistic settings. A land riven by foes and conflicts, though perhaps not those to which we have become accustomed. A land where all that we have known may not be quite as it previously seemed.

So I will ask readers to to join me on a journey. To a land that has nothing whatsoever to do with Geoffrey of Monmouth, or Chrétien de Troyes, or Mark Twain, or Tennyson. A land that owes far more to the Mabinogion than the well-intentioned attempts by some of my favourite modern novelists to interpret the classical romance tradition into more realistic settings. A land riven by foes and conflicts, though perhaps not those to which we have become accustomed. A land where all that we have known may not be quite as it previously seemed.

Recreating the Geopolitics

Most of Britain had been occupied by the Roman Empire for a period of roughly 400 years. In the aftermath, how much of Roman administrative culture survived, and how much broke down through local warlords carving out their own domains? We don’t know. And how much did people continue to live as they had done under Roman rule? We don’t know that either but, contrary to some of the “old” history, we can now see, archaeologically, that towns like Canterbury, Cirencester, Chester, Gloucester, Winchester, Wroxeter – and presumably many more – continued to be developed, with new-build taking place, well into the Sixth Century and beyond.

Meanwhile, we can be reasonably certain that, from the Third Century onwards, there had been increasing numbers of continental migrants settling mainly in the south and east of the Britannia provinces. We speculate that some of these may simply have been auxiliaries in the Roman army. Or that they were mercenaries, foederati, employed to fight in the various conflicts that beset the period. Or that they were simply economic migrants – Angles, Saxons and Jutes. This is often portrayed as an “invasion”, but there’s little hard evidence for this. Battles are cited. Dates given. Yet all the sources are questionable, to say the least.

The documents normally taken as “primary sources” for this period are: the De Excidio et Conquestu Britanniae of Gildas, originally written, we think, in the early Sixth Century; Saint Bede’s Historia Ecclesiastica (The Ecclesiastical History of the English People), written about two hundred years later; the Historia Brittonum, compiled by some anonymous editor we now know as “Nennius”, also allegedly from the Ninth Century, though the actual manuscripts are much later; the so-called Harleian genealogies, the British Library’s Manuscript 3859, itself dating from the Twelfth Century; the Annales Cambriae (The Annals of Wales) with the earliest copy dating from the Twelfth Century; and such Irish documents as the Annals of Tigernach. And then there are even later literary manuscripts – those that are now frequently described as The Four Ancient Books of Wales, priceless as historical artefacts but entirely unreliable as historical sources for the period.

That sounds like plenty of resource, yet there are very few who would be brave enough to claim these as providing the same level of “evidence” as we might expect for almost any other period of history. Only the De Excidio is contemporary and, after that, we have maybe five or six documents, scattered over the next 600 years and subject to all manner of copying errors, fashion and culture changes, political and religious tampering, literary adaptation, or simple grapevine misinterpretation. For those writing about the early Anglo-Saxon era of the late Sixth Century onwards, all of the manuscripts detailed above may provide something upon which to bite. But for those writing about the hundred preceding years, and about the very uncertain fate of the Romano-British population, they hold little of real value. So, what “new” details of the period did I discover?

Like almost everything else relating to 6th Century Britain, the extent to which Western Europe was afflicted by famines through an “Extreme Weather Event” of circa 535 AD is disputed. I was satisfied, however, that such a natural catastrophe had actually taken place, bringing widespread starvation in its wake.

Similarly, I was satisfied that it was within the boundaries of possibility that Britain was struck by an outbreak of bubonic plague during the period. Procopius and other contemporaries record the plague as devastating Constantinople in 542 AD and then spreading both east and west. Gildas refers to the pestilence in Britain in the same era, though without dating the attack. The documents now known as Annales Cambriae and the Annals of Tigernach record “a great mortality” – believed to be the same plague – hitting Ireland and Wales at this time.

A Year in the Life

Finally, I needed to construct a 6th Century calendar within which the novel’s events could be set.

So, where to start? At New Year, naturally. The end of the year’s Light Half. And New Year, for my characters, begins on the first day of November – the Calends of November, as I call it, using the Roman name for that part of the month as, I imagined, Britons of the period may have done after 400 years of colonisation by the Roman Empire. This is the festival in the Gaelic-Celtic calendar usually known at Samhain, or similar, and which I’ve chosen to translate (as others have done) as Summer’s End. My Summer’s End Festival involves plenty of feasting, naturally, and the lighting of healing bonfires, between which the breeding stock for next season – sheep, goats, pigs and cattle – would be run, between the flames, to seek the blessing of the Three-in-One, the gods Epona, Kernuno and Lug.

And then, as the Dark Half deepens, late in December, comes the Midwinter Sun Standing (Solstice), and the Roman Festival of Saturnalia, just a few days before celebration of the Invincible Sun on the day of Mithras-Birth itself. Sol Invictus. Mithras the Sun God is, of course, one of the main deities of the Roman world. Mithraism looked set to become the official religion of the Roman Empire until Constantine gave that valued place to Christianity in the Fourth Century. And there have been allegations ever since that Christianity “stole” much of its imagery from Mithraism – including, of course, the birth date of its principal personality.

At the beginning of Februarius comes the Cleansing. Imbolg in the Gaelic – Birth Cleansing Morn, as I’ve interpreted the festival. The Feast of Saint Brigid (or the goddess Brigida). The end of the First Quarter, the mid-point of the Dark Half. More bonfires, but this time with the flocks and herds driven from west to east, towards the gathering light of an almost invisible sun. And here’s how the narrator of my story, Meridden of Sea Fort, describes the day:

And if only Brigida could be induced to spread her holy light upon the livestock and the farming land, perhaps she might make us bountiful once more. Perhaps this year the Endless Winter might truly be banished. The goddess must surely know how hard these people had tried. Beds of straw had been plaited for her on the previous night, at Birth Cleansing Eve, in every byre and storage barn, each bed adorned with snowdrop heads and the white birch wand they hope she might use to dispense her blessings, with food and drink left alongside to succour her.

It had almost made me laugh, to see the desperation as family vied with family to appease this other deity, criticised their neighbours if they thought the offerings too meagre, the welcome bed insufficiently ornate. And even the monks were here to take their own share of the credit. For Holy Brigida, they claimed, had truly been a Christ-bride in Laigin, a miracle worker who cured lepers by a single touch, or dispelled disease with a single drop of blood from her finger, or brought forth magic waters from the living rock with just one tap of her staff. The Bishop of Laigin had declared her a saint, it seemed, after her death – a death that had occurred within living memory. Strange, then, that our people had been venerating the goddess for generations without number. But nobody seemed to mind. The monks’ prayers could surely not harm.

And inevitably, of course, there’s the feasting. Onion and kale cakes. Dumplings filled with slake and cockle-meat. Sweet bread too.

Close on the heels of Birth Cleansing Morn, just a few days later comes the ceremony inherited from the Romans, their Parentalia, on the Ides of Februarius, the Day of the Dead, when families may commune with the spirits of those they have lost. And their ancestors too.

Pascha next – the Passover Feast that begins with the first Sun’s Day following the Martius Equal Night (Equinox). In The Song-Sayer’s Lament, the Christ-followers celebrate Pascha as the Last Supper of the Martyrs while, for Mithras-worshippers, it marks the passing of Mithras into immortality, his ascent into Heaven. And even for the Saeson Outlanders, it is a sacred point in the year also, upon which they shower offerings to their old goddess, Eostra.

– John Collier’s “Queen Guinevre’s Maying”

And thus we come to the year’s Light Half. It’s ushered in at Bright Fire Morn. Beltane in the Gaelic festivals. The Calends of Maius. Bushes are hung about with yellow flowers, ribbon and painted shells. Cattle are gathered, similarly adorned, then ceremoniously paraded towards the drove roads for the higher summer pastures. A great time for Annual Markets too. Vendors of skin, furs, cheeses and those clever Saeson jewellery imitations of precious gems and silver cell work. Hagglers of timber, leather and linens. Auctioneers of goats, hawks, ponies, hounds and slaves. Workers of tin and copper, wax, flannel, glass, shale and jet. Pedlars of pots and tiny figurine images for the gods – Taranis and Herne; Epona and Kernunos; Danu and Arawn; Lugos and Brigid; Mithras and Yesu the Christos.

Next, far into Junius, is the Midsummer Sun Standing (Solstice) and the longest day of the year.

After that, on the Calends of Augustus, Lug’s Day (Lughnasa) – the beginning of the Light Half’s Second Quarter. A harvest festival and, in our tale, the great annual celebration of all those beliefs prevalent among those not already converted to Christianity.

There were devotees below us from just about every faith I could name. Oak Seers, yes. In great

numbers. Carrying almost a walking forest of foliage. But Mithras worshippers too, with their makeshift wooden altars and miniature Mithraeums; Asclepians, bearing the famous staff with a symbolic snake wrapped about its length, or coloured flasks representing medicines and potions; Soterians, easily distinguished by their state of inebriation, even at this early hour; admirers of Priapus, displaying all manner of phallic symbolism, and dressed in the most outrageous costumes; strings of horses, decked with garland and ribbon in honour of Epona; the young women of Nymphae, daring in diaphanous blues, greens and reds; owl-masked followers of Minerva; and the wheels of chance that stood sacred to Fortuna.

Which brings us to the end of another year!

See how these festivals and celebrations help to shape The Song-Sayer’s Lament. And let me know what you think! Creating this strange world was, indeed, a labour of love.

Leave a Reply