Three Ways to Use Foreign Language in Novels

It was my second novel, The Assassin’s Mark. The story took my main character, journalist Jack Telford, to Spain. Towards the end of the Spanish Civil War. Jack had learned some French. Some Spanish as well. And so, to give the novel colour, I used the “normal” three ways to sensibly introduce some foreign language.

First, the quick and easy method. ‘Is there a problem?’ Jack had said in his slow Spanish to the sergeant. Not ideal and only to be used when you can “show” the reader something this way, rather than “tell” them.

Second, scattering a few words that readers are likely to recognise. ‘Gracias,’ said Jack, with as little sarcasm as he could manage. ‘Muchas gracias.’ Yes, I normally put foreign words in italics.

Third, for more complex phrases. But only where I think these are absolutely essential. Normally I put the foreign phrase in italics, and then follow it with an English translation. For me, that works, since usually Jack has to translate. In his head, at least. ‘Hay un taxi…’ Jack began. There’s a taxi.

The big things to avoid? Daft blocks of foreign text nobody’s going to understand. Or simply having too many bits of foreign language. The languages equivalent of information dump. And, like every other sentence in the book, not having dialogue, foreign or otherwise, that’s simply dull.

And in Historical Fiction?

But what’s any of this got to do with historical fiction, specifically?

In The Assassin’s Mark, I had an additional problem. It was an important part of the plot that Jack should spend some time in the company of guerrilleros in the mountains of Asturias. Yes, shades of For Whom the Bell Tolls. Only Jack plainly doesn’t have Robert Jordan’s fluency in Spanish. Not then, anyway.

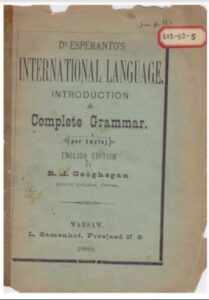

Early in the novel I’d introduced the detail that, in Manchester, Jack had been President of the university’s Esperanto Movement. It was perfectly valid. In the 1920s and 30s, any self-respecting young man on the Left would have dabbled in Esperanto. As it happened, Jack Telford had a flair for it. During his trip to Spain, he even carried a prized but neglected copy of Richard Geoghegan’s Doctor Esperanto’s International Language.

Esperanto had, of course, been invented in the late 1870s by Ludwik Zamenhof. His intelligent attempt to create a global language. One that was relatively easy to learn. Avoiding the need to study a plethora of other foreign languages. And so that “all nations would be united in a common brotherhood.”

An Introduction to Esperanto

In the UK, the Esperanto Association of Britain (the EAB) was created in 1904. It’s still going strong.

Esperanto itself flourished in the aftermath of the First World War. The horrors of that conflict drove so many towards the logic of internationalism. Remember? The war to end all wars? But that was, in itself, anathema to the more totalitarian regimes. Thus, Esperanto was banned in Nazi Germany, in Francoist Spain, in Imperial Japan and in Stalin’s Russia.

Esperanto in The Assassin’s Mark

But among the socialists and anarchists of Republican Spain? Yes, it would have been commonly used. A good historical device, therefore. Like this…

‘¡Coño!’ said the Jefe. ‘Vi parolas Esperanton, sinjoro Telford.’ You speak Esperanto. ‘Kie vi lernis?’ Where did you learn?

‘Ĉe Universitato,’ Jack replied. ‘Prezidanto da la societo.’

After that, and a couple more samples, I could simply leave Jack and the Jefe to chat in English, the use of Esperanto simply being implied.

How to test it, though? I’d dabbled in Esperanto myself as a teenager in the 1960s. But I couldn’t rely on that. So, it was Tim Owen at the EAB who kindly read through each piece of Esperanto in the novel. Tim either approved or corrected. Superb!

Esperanto Today

And for those whose interest in Esperanto might have been piqued by this blog, you may like to know that there are an estimated 100,000 “active” speakers of the language around the globe. Apart from those, the online Esperanto learning platform Lernu! claims to have an additional 150,000 students. While the language platform Duolingo claims to have 294,000 students learning Esperanto through English, 244,000 through Spanish, 220,000 through Portuguese, and 72,500 through French. They’re currently developing an Esperanto course for Chinese Mandarin speakers, as well.

Maybe we should all start writing our novels in Esperanto!

If you want to know more, just get in touch with the Esperanto Association of Britain (or wherever in the world you happen to be) website. Their UK conference begins on 22 April 2022 – in Conwy, North Wales. Hopefully, I’ll be there.

As a final footnote, many of you will know that, for big chunks of each year, we live in Guardamar del Segura, just south of Alicante, Spain. A few years back, the local council decided to dedicate one of its small roundabouts to – yes, to Esperanto. Here it is. A bit faded. But a daily reminder, whenever I walk past, of Esperanto’s part in the world – and in The Assassin’s Mark.

In a subsequent post, I’ll talk some more about using “foreign language” in two more novels – The Song Sayer’s Lament, set in 6th Century Britain, and then The Last Campaign of Marianne Tambour, my telling of the 1815 Waterloo Campaign, but told from a French viewpoint.

Leave a Reply