In 1876, most people would have been familiar with George W.M. Reynolds and I couldn’t help including him in a couple of chapters in Blood Among The Threads.

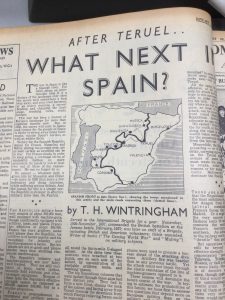

But I originally ran into George Reynolds about ten years ago. I was writing the first of my Spanish Civil War novels, The Assassin’s Mark, and I needed to find an appropriate real-life newspaper for which fictional protagonist and journalist Jack Telford might work. It needed to be a politically progressive paper, but nothing too obvious. And Reynolds News fitted the bill perfectly. A well-established Sunday newspaper with the habit of speaking out about issues around which most of the popular press feared to tread. Its editor at the time, Sydney Elliott, for example, was the first to condemn Chamberlain’s “Peace for our Time” speech rather than praising it.

And the icing on the cake?

Just about every single copy of Reynolds News for the period is available in the archives section of Bradford University. Most of the pink pages are pristine though some, sadly, are copies which had already begun to crumble into decay before they came into the university’s collection. I had the chance to spend some time with the archives and put together a lengthy piece for my own blog about how Reynolds News reported the progress of the conflict in Spain: https://www.davidebsworth.com/reynolds-news-and-the-spanish-civil-war.

This valuable resource helped me to feature Reynolds News through two further Jack Telford novels. One more set at the end of the Spanish Civil War (Until the Curtain Falls) and the third, a blockbuster following Telford through the whole of the Second World War – though from an unusual point of view – A Betrayal of Heroes.

It was Reynolds News, of course, which gave the cartoonist Giles his first big break, long before he went to work for the Daily Express. And it was while researching Sydney Elliott that I first became intrigued by George W.M. Reynolds himself.

Born in 1814, Reynolds became a best-selling fiction writer and rival to Dickens; a Chartist; a radical newspaper editor and journalist; and an entrepreneur. During his lifetime he was more widely read than Dickens or Thackeray. He is credited with publishing perhaps 40 novels and a batch of short stories, as well as editing at least 8 journals and newspapers.

Reynolds, in fact, had the temerity to “borrow” Dickens’s Samuel Pickwick and include him in two stories of his own. These were Pickwick Abroad and Pickwick Married. But the, as his biographers, Stephen Basdeo and Mya Driver, remind us, Reynolds spent his years in Paris in company with many of France’s upcoming authors including Victor Hugo. They remind us, also, that the plot of Reynolds’s story, Alfred de Rosann: The Adventures of a French Gentleman (1839), bears an uncanny resemblance to Les Misérables – published in 1862.

Reynolds died in 1879 and, in his obituary, the trade magazine The Bookseller called him “the most popular writer of our times”

So it was that, this past year, I began working on my twelfth novel, Blood Among The Threads. Basically, this is a murder mystery set during the Art Treasures Exhibition and National Eisteddfod both held in Wrexham, North Wales, in 1876. As it happens, this one also features a journalist and since most of my stories have threads of their own to link them together, I decided it would be neat and quirky to have him working for – yes, Reynolds’s Newspaper, as it was in 1876.

In the way of such things, however, the developing plot soon made it clear that I’d need to have George William MacArthur Reynolds appear in person within the novel. It seemed fitting, since I already knew about his Mysteries of London. But now I downloaded a copy and read it. I also picked up a facsimile copy of The Parricide. It felt like a good way to get inside the man. And it was equally helpful to read Reynolds’s writings, his editorial pieces for the newspaper, from 1876 itself.

Naturally, Reynolds was then 62, eighteen years a widower, and only three years away from his death. How to picture him, therefore? Here he is, having travelled up from Herne Bay to Chislehurst for a meeting arranged in the Bull’s Head Inn, playing a hand of cribbage with Palmer, the novel’s main protagonist and half Reynolds’s age:

There was bitterness in his satire as he set two cards of his own on top of the pair already laid face-down by Palmer. He ran a hand through the tumble of boyish waves and curls spilling across his left temple, though the hair purest white, like bleached parchment. He was clean-shaven as well, which helped Reynolds fight against the outward evidence of his own autumn years.

And Thetford-born Palmer’s impression of the great man?

Dickens? Trollope? Thackeray? No, here was the true literary legend of the age. George William MacArthur Reynolds. And not literature alone. Palmer had never heard Marx or Engels speak but he had read transcripts of their speeches. He did not agree with all the doctrines they proclaimed but there was enough to chime with much of his Primitive Methodism. Yet, before Marx, before Engels, there had been George W.M. Reynolds. Palmer’s father introduced him to Reynolds’s writings alongside Thomas Paine’s Rights of Man – for had Paine not also been a son of Thetford? Synergy.

Finally, Reynolds’s republican views and his other political opinions form much of the novel’s backdrop.

Palmer pondered Reynolds’s republicanism. His depictions of royalty in his novels were at times portrayals of the dissipated, the greedy, the depraved.

‘Is monarchy truly such an abhorrent part of our system?’ he said.

‘The crowned miscreants and harlots of Europe’s royal families? Surrounded and sustained by tier upon tier of aristocrats with their obscene wealth. Wealth possessed simply because they are descended from the whores of Charles the Second. Or because their forebears were professional plunderers and despoilers. Hereditary aristocracy which breeds our passion for privilege over merit. How does it feel, Mr Palmer, to be a subject rather than a citizen? For there, my friend, is the fly in their anointment.’

Reynolds beamed at his own jest.

‘From my own limited studies, sir,’ Palmer replied, ‘I believe the election of the American Republic’s presidents to be an equally imprecise way of selecting a head of state.’

A cheer and raucous laughter from the skittles alley as the ninepins were scattered once more.

‘Of course,’ said Reynolds. ‘Yet that election itself has a symbolic value, does it not? The will of the people. In Britain, it is not the individual members of the royal family with whom I find fault but the system they represent. Inheritance? Inherited privilege? And our present monarch seems praised essentially for her neutrality in political matters.’

‘Does that not run entirely contrary to your defence of democracy, Mr Reynolds? I do not disagree with you in that regard, either. But if we elect a government by the will of the people, should they not be allowed to govern without interference from an inherited crown?’

‘A neat tautology, my friend.’ He slammed his hand on the oak tabletop in delight. ‘For what, then, is the point of a head of state who presides over such poverty and pain as we see among the working people of our great cities – and lifts not a finger from her gilded throne to help them?’

They spent a pleasurable hour finishing their food and debating the other causes so often espoused by Reynolds in his writings and editorials. Universal suffrage as a protection against despotism. The conviction that the cause of Chartism would one day prevail and bring an end to false systems and corrupt institutions. His pity for the white slaves of England in its factories and fields. The fiction of Britain’s glorious constitution. The dream of a federal union of democrats, first in Britain, then across all Europe. The way that steam power had annihilated time and distance – and how much more those demons could be reduced should plans for the canals at Suez and Panama come to fruition. And his contempt for Disraeli’s stance on the Eastern War, the Prime Minister’s continuing advocacy for the Sublime Porte – for the Turkish oppressors of the Balkans – despite the plain wishes of the British people to the contrary.

Just a few excerpts. But I hope they give a flavour of how George W.M. Reynolds might have been if we’d been lucky enough to meet him. I was hugely privileged to be asked by the Reynolds Society to write an article for their website – this article. Hope you enjoy it!

Leave a Reply