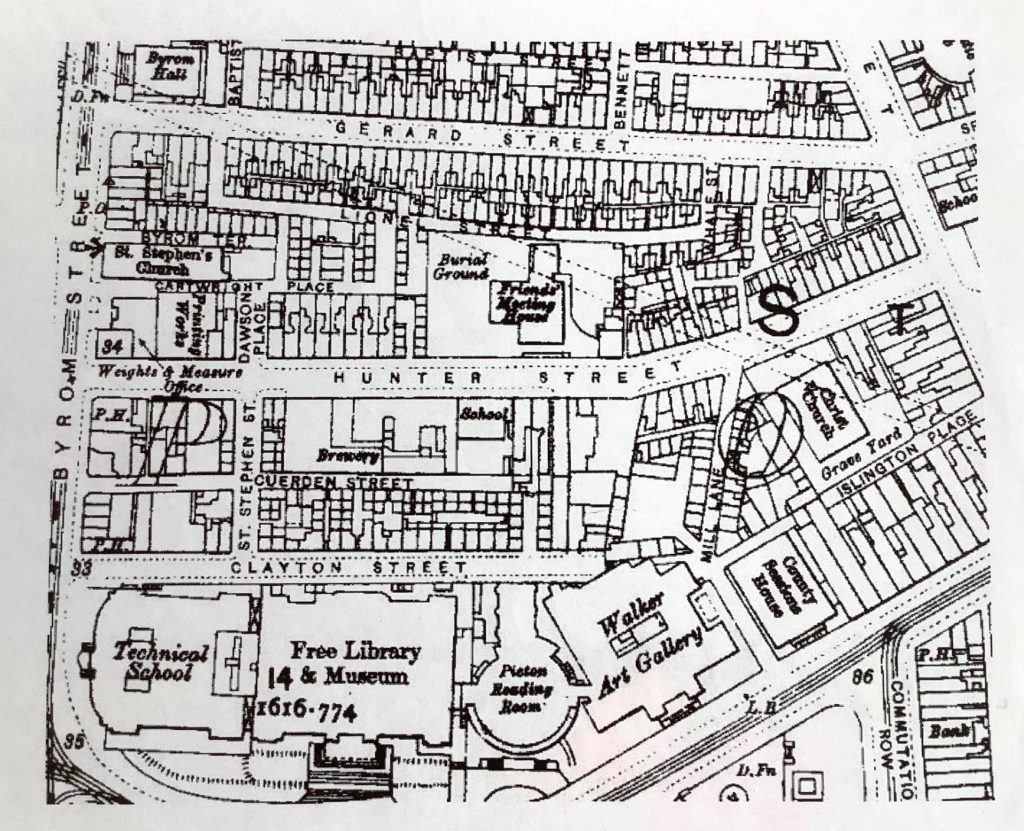

Hunter Street is now no more than a busy dual carriageway, running behind Liverpool’s Walker Art Gallery and the Museum. The road connects the bottom of Islington with the end of Byrom Street. It carries an endless stream of vehicles heading in one direction, upwards, for the city’s eastern suburbs. To the M62 motorway, the cathedrals and South Liverpool. Or in the other direction down towards the Mersey Tunnels, Dale Street and the waterfront, as well as towards Bootle, Walton and the north.

More or less, like this!

Back in the 1960s, it looked like this…

…with Gerard Gardens, subsequently demolished, at the top of the hill.

But in 1911 it was a more modest though far more interesting thoroughfare. Terraced houses and businesses. A mass of other smaller streets leading off in both directions. Spencer Street, Carter Street and others at the top, where Gerard Gardens would later be built. Christ Church and the Friends Meeting House. Poulterers, tinsmiths, chandlers, saddlers and tailors. Towards the bottom, Mellor’s Brewery and Avery Weighing Machines.

On one corner with Byrom Street (and still there on the right of the 1960s photo), the Byrom alehouse, known locally as Mad John’s. On the other, Lunt’s Bakery and the Weights and Measures office. And just next to the office, a printshop.

The printshop was owned by William McCall and, later, by his stepson, John Joseph – who had been brought up with McCall’s surname but had, in fact, been born John Joseph Ebsworth. And there my tenuous personal link to the tale ends. Almost.

My maternal great-grandmother, Sarah, married a German sailor named Ernst Jurks. Ernst died in 1912, and though Sarah herself kept the surname for the rest of her life – she died at her home on Great Mersey Street in 1955 – most of their male offspring changed their name to Kirk from 1914 onwards.

Then, the Welsh connection. The Census records reveal that my paternal grandmother (who died after having given birth to fifteen children) was Frances Davies, born in Denbigh and later emigrated to Liverpool. When I was a kid, one of the local churches, on the corner of Trinity Road, was a Welsh chapel.

And since I had friends just near that part of town, it was a regular part of my young life to hear Welsh spoken on our Bootle streets. Chunks of my childhood were spent happily on the hills of North Wales with my sister Joan and her husband Tony – to both of whom I owe a great deal. But for the past forty years and more I’ve been living in Wrexham, North Wales, with Ann, with Welsh-speaking friends, and even a Welsh-speaking Polish daughter-in-law. So, the Liverpool Welsh connection is, I think, strong in me.

My final personal link to this yarn? The unions, of course. The National Transport Workers’ Federation mentioned in some of the chapters was destined to fall apart within a few years, though many of the individual transport-related unions, as well as some of the newer unions for those men and women labouring in a whole mass of other industries and sweatshops, would come together in 1922 to form Britain’s mighty Transport & General Workers’ Union.

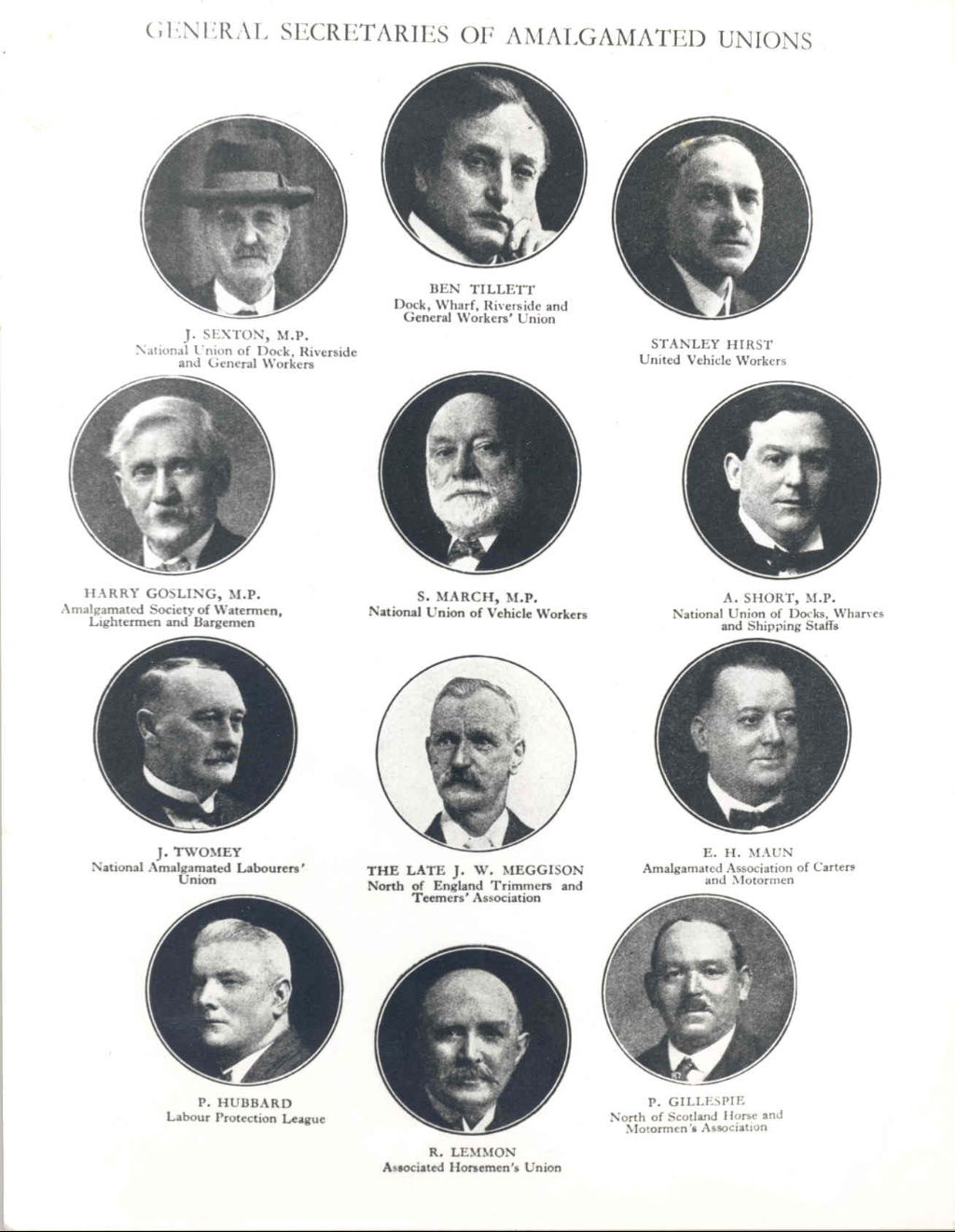

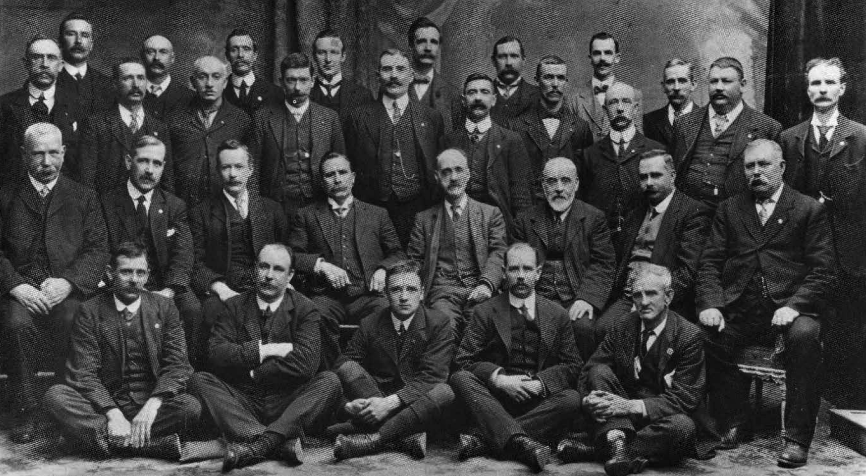

The T&GWU’s “founding fathers” – and yes, all men. But at the top left, Jim Sexton, who features in the novel.

The T&GWU was extended home and family to me from my own early twenties onwards. Mighty indeed. Its General Secretary, Ernie Bevin, would serve as Minister of Labour and National Service within Churchill’s wartime coalition government. A later General Secretary, Jack Jones – friend, comrade and veteran of the Spanish Civil War – would lead the T&GWU to even greater prominence in the 1970s. I hope this novel, published a hundred years after the union’s creation, will serve as my own modest reminder of the part played by trade unions in general, and the T&GWU in particular, in 20th Century social, industrial and political history.

![Billy Bragg at International Brigade memorial ceremony [22 July 2007]](https://www.london-se1.co.uk/news/imageuploads/1185141990_62.49.27.213.jpg)

Our old friend Jack Jones, in later life, speaking at an International Brigades rally.

The House on Hunter Street is, of course, a work of fiction but, as always, I’ve done my best to keep the fiction within the boundaries of historical veracity, to remain faithful to the historical events giving the story its background.

Intriguing events: the industrial unrest that brought Liverpool “near to revolution” in 1911 and beyond; the battle for women’s suffrage, which ignited the city and the country as a whole during the second decade of the Twentieth Century; the many racial and cultural tensions apparent along the Mersey during that same period; and evidence of the build-up to an appalling Great War already there for anybody with eyes to see. Interlinked events, some of them almost too strange to be true, that cried out to be brought to life in the way that, in my humble opinion, historical fiction does so well.

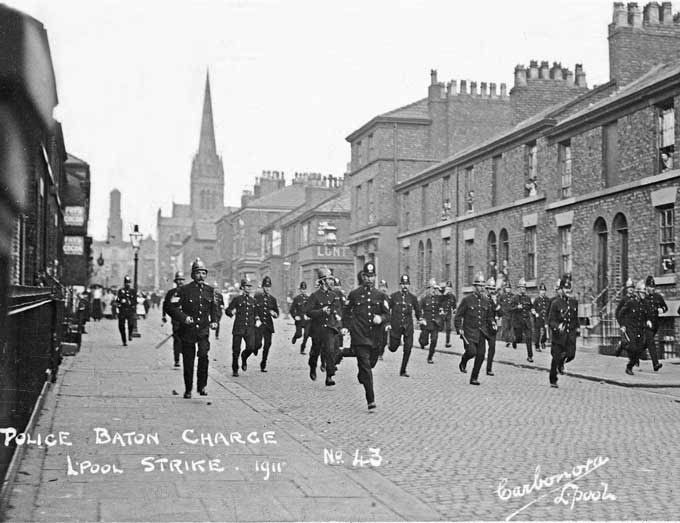

Liverpool under Martial Law, 1911

Those events – both on the national scene as well as the incidents in Liverpool – are chronologically as correct as I could make them. Though it’s maybe worth specifically saying that to reconstruct the events of Liverpool’s Bloody Sunday on 13th August 1911, I mainly used The State Response to 1911 by Professor Sam Davies (deceased), from Liverpool John Moores University. Many of the eye-witness accounts of the city’s Bloody Sunday are either contradictory or partial.

Tom Mann’s account, for example, fails to even mention the police and soldiers pouring from within St. George’s Hall, something that others say took place during the early stages of the unrest. Similarly, his mention of the Mounted Police reads like he’d been told about this afterwards. The logical conclusion is that this phase of the action took place slightly later, as Sam Davies had suggested, after the police charges over the road in Lord Nelson Street, and just after Tom Mann had finally drawn proceedings to a close and himself left the Plateau. In any case, the novel simply relates the sequence of events as remembered by my (fictional) characters, Cari Maddox, Amos Gartee and Tom Priddy – any of whom may equally have got things slightly out of kilter.

I first came across the separate – and largely ignored – strike by Elder Dempster’s West African Kru seamen maybe twenty years ago in archive copies of Liverpool’s Daily Post for 16th March and 23rd March 1911. Then again on 22nd June. And a bit of a mystery here since, when I went back to the archives in Liverpool’s Central Library, the relevant microfilms for March 1911 were missing. And there no longer seems to be any other copy in existence for the relevant editions. Strange, though we continue to search.

But between the Post, the Echo and the Courier, we can at least piece together some of the threads. On 16th March, one hundred black stokers and trimmers on strike against Elder Dempster, beginning with the crew of the Mendi, three weeks earlier. Four other crews had subsequently joined them, protesting about only receiving half the pay of white seamen in similar roles. On 17th March, Kru seamen visited the Echo office. Elder Dempster prepared to make some sort of offer if they returned to work but otherwise would take them “free” back to Sierra Leone and replace them with white crews. There’s a mention that they’d sought help from the National Sailors’ and Firemen’s Union, but no indication that any such help was forthcoming – simply a note that they weren’t members of the NSFU.

The Elder Dempster’s SS Mendi, later – on 21 February 1917 – struck by a larger British ship in thick fog and sank in the English Channel. On board were nearly 900 men – mostly black South Africans – on their way to support the war efforts on the western front. More than 600 lives were lost.

On 21st March 1911, the Echo reported an offer by Elder Dempster to increase the black stokers’ pay by five shillings per month, though the offer declined and the seamen preferring to be returned to West Africa. Then, on 23rd March, a report that some already taken back to Sierra Leone and sufficient white seamen replacing black crews on the Zaria.

On that same date, mention of a large meeting of seamen and dockers at St. Martin’s Hall on Scotland Road, Liverpool, with African seamen in attendance and apparently congratulated on their dispute. This meeting also received the news that a more widespread seamen’s strike was imminent. But then no further mention for quite some time. My own account of another meeting at St. Martin’s Hall on 22nd May is, therefore, an invention. There may, of course, have been other such meetings but, if so, they never received any coverage.

On 19th and 21st June, news of more black sailors on strike from Elder Dempster’s Aro and, once again, the Aro’s crew replaced with white stokers. On 23rd June, a similar story in relation to the Gando but an indication that Elder Dempster’s black seamen were prepared to settle for concessions – though the details weren’t reported. After this, the following week, simply a report that the outcome was positive but, again, no details. I’ve invented some of the detail about Elder Dempster replacing one crew of black sailors with another, though in practice the Company mostly hired white crews to replace them.

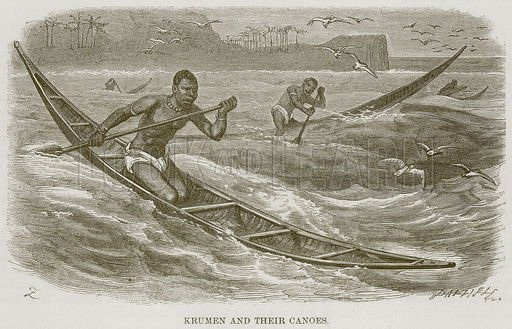

I was therefore keen to tell at least part of the story from the viewpoint of the Kru seamen, though that posed problems of its own. How to realistically give a voice to Amos Gartee and his fellow-strikers. The research for this was complicated, and I may well have got the end result completely wrong. The Kru, of course, have their own languages – part of an entire family of languages prevalent, at least in the early 1900s, throughout that area of Liberia, Sierra Leone and the Ivory Coast. And within each language, a mass of dialects. In the case of Nana Kru, in Liberia, the language known as Daloa Bété, or simply Bété. And where I couldn’t find the vocabulary I needed, I borrowed words from neighbouring tongues – and hence my use of poto for “white.”

The Kru- and the legendary tales of the seamanship and boat handling skill

In addition, there was – and still is – a form of vernacular creole Liberian English, known as Liberian Kreyol (also in the West Indies) or sometimes Kolokwa. In neighbouring Sierra Leone, this is Krio, still hugely widespread. So, it’s Kreyol which Amos uses most often when he’s speaking English – though it’s a massively simplified form of this vernacular, to make it easier for contemporary readers in English. I just hope it works – and apologies if it doesn’t!

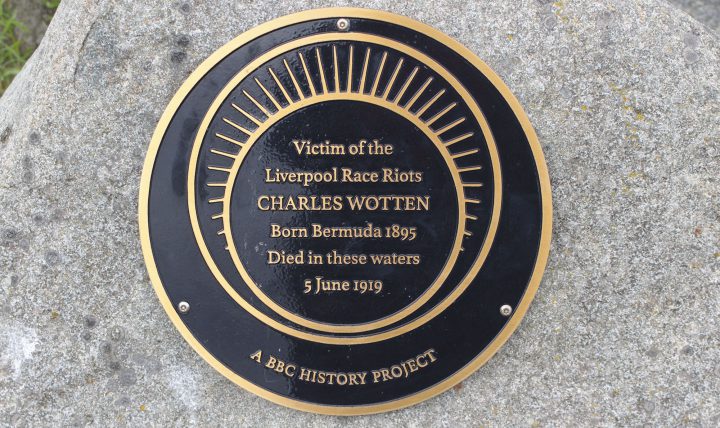

But my story also finishes with a relatively happy ending, which doesn’t properly do justice to the actual experiences of the black community in Liverpool over the ensuing years. The publication Great War to Race Riots (Madeline Heneghan and Emy Onoura) and the archives on which it’s based show us that, while the 1911 strikes may have led to some temporary improvement in the pay of Elder Dempster’s West African seamen, the gains were short-lived. And how, despite the huge contribution and sacrifices of our black community during the First World War, it quickly became a scapegoat for post-war unemployment and a shattered economy. Then, the attempts to “repatriate” African and West Indian seamen who had already settled in the city, as well as the race riots of 1919 – which culminated in the murder of seaman Charles Wotten by a racist mob. They are issues which still resonate in Liverpool and elsewhere to this day.

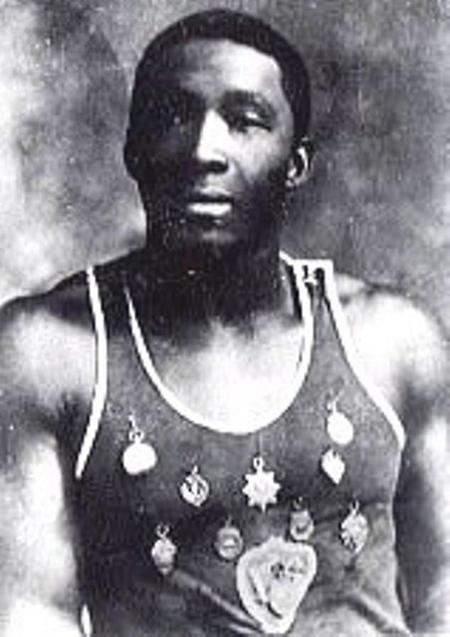

Most of the fictional characters are not intended to represent anybody in particular, though Charles Tuohey – or Abdul Niasse – was based in part on the real-life James Clarke, born in British Guiana and, having stowed away on a vessel bound for Liverpool, was adopted by an Irish family. He worked on the docks and was also a swimming instructor. He became famous in the city and James Clarke Street, in Liverpool 5, is named in his honour. The character was also partly inspired by another old friend and comrade, Eric Scott Lynch, who initiated the Slavery History Rails in Liverpool, and one of the stalwarts instrumental in establishing the International Slavery Museum in the city.

James Clarke

A mention here for Mary Clarke also, who was indeed one of our first black women footballers, though somewhat overshadowed by her more famous sister Emma.

And Emma Clarke

There are, of course, many other real-life personalities, who make appearances in the plot and I hope I’ve not been unfair to them, nor to the historical events in which they were a part. My King Billy character, for example, is based on William Henry Jones, 43 in 1911, from Kirkdale, one of the 1911 strike leaders and, in the following year, destined to become General Secretary of the Merseyside Carters’ Union. Amos Gartee’s Jocota, is based on Joseph Patrick (Joe) Cotter, born in 1887 and also a 1911 strike leader for the Ships’ Stewards, Cooks, Butchers and Bakers Union – though Joe remained an intractable opponent to the employment of non-British workers. Billal Quilliam, not simply the union’s solicitor, but also a high official within the Carters’ Union itself. The dockers’ leader, James Sexton.

The 1911 Strike Committee. Back row: fourth from left, Billal Quilliam. Third row: second from left, Bill Jones; fourth from left, Joe Cotter. Second row: fourth from left, Tom Mann; fifth from left, Jim Sexton.

This story owes a great deal to my friend and fellow-writer, Lucienne Boyce, who frequently provided mentoring for me on the complexities of the suffrage movement. And my thanks also to Liverpool University History Graduate, Liam Davies – now himself a fine history teacher – who served a short internship as my researcher during the summer of 2017. Liam’s report contributed significantly to my wealth of knowledge on some of these topics.

I am indebted as well, naturally, to Ann and the many and various beta readers who’ve been helping me pore over the final drafts. I particularly want to mention Pauline Vickers here for her massively detailed and astute comments. Also, Professors Philip Thulla and Osman Sankoh in Sierra Leone, as well as Hanna-Ruth Thompson in London, for their patient guidance on the Kru and related language issues. Dylan Hughes was invaluable on Welsh language snippets and reminding me about the Penrhyn Quarry disputes. Thanks to Frank Hont for his valuable support and to our old friend and comrade Donna Kassim, who caused me to revisit many of the cultural issues with fresh eyes. To Jeremy Hawthorn, retired criminal defence solicitor and prominent historian, for his depth of knowledge around the 1911 Transport Strikes, timelines and related issues. Jeremy has devoted considerable time and energy trying to keep my fiction within those crucial boundaries of historical veracity.

Finally, for anybody who’d like to take a closer look at just a few of the main resources I used in writing this tale, here is a more detailed list.

For 1911 Transport: Liverpool Transport, Volume 2: 1900-1930 by J.B. Thorne and T.B.Mound; Liverpool Corporation Tramways Handbook: 1903-04 (Archives Section, Liverpool Central Library); and my thanks to Joe Lane and the team at the National Railway Museum, Leeds.

For Liverpool life in 1911: Pat O’Mara’s The Autobiography of a Liverpool Irish Slummy; John K. Walton’s Fish and Chips, and the British Working Class, 1870-1940; and various editions of the Liverpool History Society Journal (2008).

For the Black Seamen’s Strike, Liverpool 1911: Liverpool Central Library’s 1911 archive copies of the Liverpool Echo, Football Echo and Daily Post; Race, Law and the Chinese Puzzle in Imperial Britain by Sascha Auerbach; Work and Community among West African Migrant Workers since the Nineteenth Century by Diane Frost, as well as Diane’s research article, The Kru in Liverpool since the late Nineteenth Century (from the journal Immigrants and Minorities, Volume 12, 1993, Issue 3); Black Salt: Seafarers of African Descent on British Ships by Ray Costello; and David Killingray’s Africans in Britain. More recently, the Writing on the Wall project which resulted in the publication Great War to Race Riots by Madeline Heneghan and Emy Onoura. But apart from those sources, we know little about the dispute’s day to day details and much of what appears in the novel is, by definition, my own invention.

For the Suffrage Movement nationally: The Women’s Suffrage Movement in Britain, 1866-1928 by Sophia A. van Wingerden; The Bristol Suffragettes by Lucienne Boyce; Lucienne Boyce’s web page: Women’s Suffrage Timeline (lucienneboyce.com); Hannah Mitchell’s autobiography, The Hard Way Up; and the Google News Archive (news.google.com) site, Votes for Women section.

For Liverpool and Merseyside Suffragettes: Mrs Brown is a Man and a Brother: Women in Merseyside’s Political Organisations, 1890-1920 by Krista Cowman; and Votes for Women: The Events on Merseyside, 1870-1928 by Marij Van Helmond.

For Liverpool Carters: Paul Smith’s ‘A Proud Liverpool Union’. The Liverpool and District Carters’ and Motormen’s Union, 1889-1946: Ethnicity, Class and Trade Unionism, published by Liverpool University.

For the 1911 Transport Strike: James Sexton’s autobiography, Sir James Sexton, Agitator, the Life of the Dockers’ MP; Tom Mann’s autobiography, Tom Mann’s Memoirs; Nerve magazine’s 1911 Transport Strike Calendar; Strike – 1911, by Harold Hikins; Eric Taplin’s Near to Revolution; The rank-and-file in the 1911 Liverpool General Transport Strike by Sam Davies (deceased) and Ron Noon; the website for Mills Media (formerly Carbonora Photography); Hansard, August 1911; and Jeremy Hawthorn’s superb article for the North West Labour History Group, So why not have a go? The Liverpool Transport Strikes of 1911.

Many thanks for reading!

This book sounds so interesting and a potted history of unions and Liverpool seafarers. Can it be pre-ordered?

Hi Rhoni. Not available for pre-order just yet but soon – and will keep you posted. Stay safe.

This is fascinating. Thank you. I came across your piece while looking for references to Rumbold, the hangman character in James Joyce’s Ulysses. He was from 7 Hunter Street! “7 Hunter Street,

Liverpool. To the High Sheriff of Dublin, Dublin.

Honoured sir i beg to offer my services in the abovementioned painful case i hanged Joe Gann in Bootle jail on the 12 of Febuary 1900 and i hanged…”