There are already plenty of walking tours in Spain’s capital city but, during a recent visit, I was reminded just how many of its key Spanish Civil War locations get a mention in my second Jack Telford novel, Until the Curtain Falls.

The conflict began, of course, with a military rebellion against the elected Republican government in July 1936. It was led by several key generals, including Francisco Franco, who quickly enlisted the help of Hitler and Mussolini. Between them, they sent aircraft, U-boats and tens of thousands of ground troops to help the rebels, while the loyalist Republicans received tanks and other support from Soviet Russia, as well as 35,000 International Brigade volunteers from 53 different countries.

By October 1936, Madrid was under siege and would remain so until the war effectively came to an end in March 1939. Despite all his foreign assistance, the city never fell to Franco. His Nationalist forces only entered Madrid when the war was lost.

Because of this level of international involvement – and since the major foreign belligerents, Germany, Italy and Russia plainly used the Spanish Civil War to “practice” for the even wider conflict they knew was coming – there is a growing view that the Second World War didn’t actually start with the invasion of Poland in 1939, but actually with the siege of Madrid in October 1936.

So, here is the tour.

1. Temple of Debod and Site of the former Montaña Barracks

I thought the tour should start here since it is, after all, the site of one of the opening incidents of the Civil War.

This authentic Egyptian temple, dating back to the 2nd century BC, was transported from Egypt, here to Madrid’s Cuartel de la Montaña Park. In the 1960s, Egypt requested international help to save the temple from being damaged by floods following the construction of the Aswan Dam. To thank Spain for the country’s generous donation, the Egyptian government gifted the temple to the city of Madrid.

The temple and its gardens now occupy the site where the Cuartel de la Montaña once stood. But this is also where Napoleon’s French troops shot the rebels of the uprising of 2 May 1808, a scene famously depicted in Goya’s 1814 painting The Third of May 1808.

A century later, the same location witnessed the military uprising in July 1936 which led to the Spanish Civil War. During the conflict, the barracks were heavily damaged and subsequently demolished.

In the novel, Jack Telford comes here with the real-life Republican Catholic priest, Father Leocadio Lobo:

They stood on the broken ramparts of the old Montaña Barracks, wrapped in their overcoats, looking down from the upper slope of the ridge, over the Parque Oeste, towards the Manzanares River, the Casa de Campo beyond – all of it resembling nothing so much as the churned devastation of the Western Front – and north to the ruins of the University. For Madrid, it had all begun here. The day after Franco’s insurrection. The General’s misguided belief that the garrisons of Madrid would rise in his support. But they had not. And when the fascists had seized this barracks, the milicianos and Republican Assault Guards had taken it back in just two days, destroyed the place in the process, left many of the defenders dead in its rooms and revetments, killed others later at the Modelo Prison.

He pointed to a hill in the middle distance.

‘On Cerro Garabitas. That’s where they’ve got all their heavy artillery. When you see the shells fall on Madrid, that’s where they’re coming from. We tried to dislodge them a dozen times, but never succeeded.’

The Cerro Garabitas is plainly visible from the Debod Temple, or from various other viewpoints, like the esplanade at the Royal Palace. The prominent hill about 3 kilometers away to the north and west (surmounted by a fire-watch tower) is worth a visit anyway but, from here, it’s easy to see the way that Franco’s own artillery, and the German artillery under his command, was so easily able to hit key targets.

It’s harder to see the University from here, but it lies just to the north and is worth a visit, in itself. The University complex was the only part of Madrid which Franco’s forces succeeded in penetrating throughout the entire complex – and, even then, only partially. But the novel gives a flavour of the bitter fighting in this zone:

‘On a battlefield,’ said Father Lobo, ‘there are few atheists, my son. But I never want to be in a place like that again,’ the priest went on. ‘Not ever. Our milicianos fought them room by room. Corridor by corridor. Lecture hall by lecture hall. I remember blessing a boy. Dying behind a barricade. And that barricade was built from great mounds of Encyclopaedia Britannica. You know where? In the Facultad de Filosofía.’ The University’s Philosophy Faculty. ‘You can’t see it from here. But it’s up to the north. All in ruins now. Just a mile away. Such ironies!’

2. Plaza de España

The Plaza de España, just steps away from the Temple of Debod to the north, and the Royal Palace to the south (and on the previous map), was developed in a project which began in 1911. Where previously stood fields and a convent that was later used as a barracks, an open space was devised for the citizens of Madrid. The plaza was designed to pay homage to Spanish history and culture, with monuments dedicated to cultural and historical figures such as Miguel de Cervantes and Carlos III. But it was an easy target for Franco’s artillery and most of its original buildings were completely destroyed during the siege:

Jack had just walked here with Father Lobo. They’d passed through the rubble of Plaza de España on their way from the Metro. He knew how close it was.

Stories of the hotels and bars from the area gave me the title for the book. Many accounts of the advice always given by waiters to their guests. Because the local A.B.C. newspaper always carried details of performance times for all the theatres and cinemas, both here and all the way along the Gran Vía. There were many Nationalist supporters trapped in Madrid, of course. Rebel General Mola had boasted that, in addition to his own four army columns, that he had a “fifth column” within the city itself. And, thus, the term was born. These “fifth columnists” could easily pass copies of the newspaper out to the besieging forces, so that, if a particular show was due to finish at a particular time, the artillery on Cerro Garabitas would zero-in on the departing audience. The advice from Madrid waiters, therefore? “If you’re going to see the show, leave early. Don’t wait until the curtain falls.”

And those “fifth columnists” included Captain Edwin Christopher Lance, a veteran of the First World War, an adventurer, soldier of fortune and engineer. He’s generally classed as a hero, due to author and historian C.E. Lucas Phillips and his book, The Spanish Pimpernel – which credits Lance with helping prominent Nationalists (and sometimes Republicans, as well) from the cruelties of the “Red Terror”. So, a comparison with the Baroness Orczy’s Scarlet Pimpernel, helping those poor aristocrats from the guillotine! Lance’s exploits were certainly remarkable, though my own research into the man’s life prevented me from casting him in the role of “hero”. He died in Alicante in 1970.

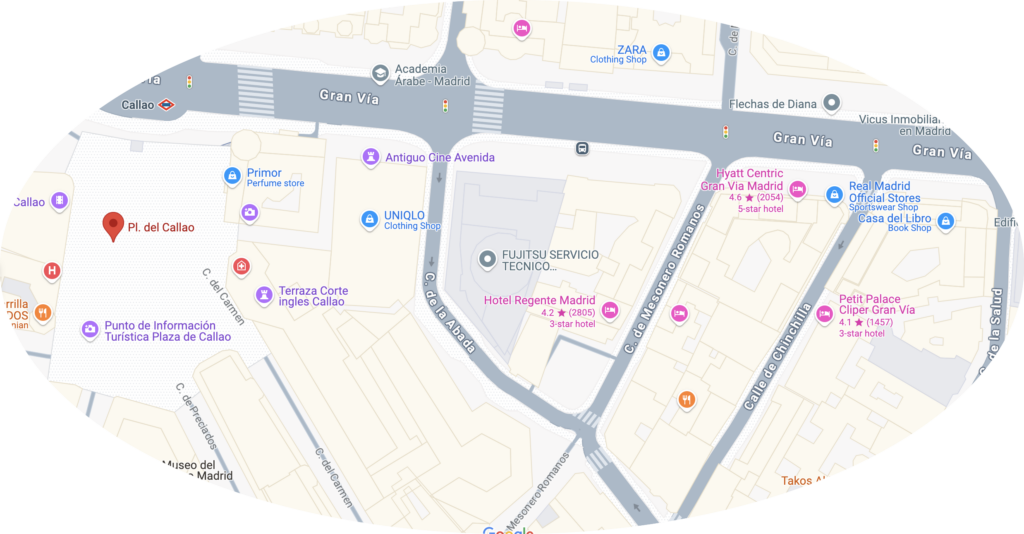

3. Plaza de Callao and Calle Mesonero Romanos

Sadly, the Hotel Florida no longer exists, though its easy to find its former location. It stood in the Plaza de Callao, at Number Two. It was built in 1924 and was used as a base by many of the foreign correspondents stationed in Madrid during the Spanish Civil War. While based in Spain as a correspondent for the North American News Association (NANA), Hemingway stayed at the hotel, where he wrote a play. The hotel was demolished in 1964 and a new building for the Galerías Preciados department store was built on the site.

Telford was there, of course, along with real-life Father Leocadio Lobo:

‘I did not like Hemingway very much,’ Father Lobo was explaining later, in one of the bars in the Hotel Florida. Jack admired the American’s writing style and had suggested meeting at the Florida as part of his personal homage to the man. The place had once been majestic, then the haunt of celebrities and prostitutes, afterwards yet another hospital, now simply as worn by war as the rest of Madrid. ‘Not enough interest in telling the truth. The whole truth.’

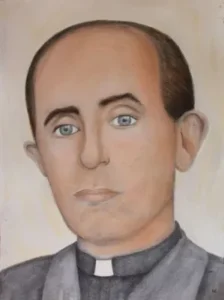

And, while we’re here, I might as well explain Father Lobo.

Much of the criticism of the Republican side in the conflict centres around the so-called Red Terror – atrocities committed by Republican supporters and particularly the killing of priests. An allegation that Republican loyalists were all godless heathens. But, of course, many of the Republic’s soldiers were also devout Catholics and plenty of accounts of Republican priests performing the Mass before battles. Father Lobo remained in Madrid for this purpose throughout the siege and he famously became involved in a letter-writing campaign to counter this propaganda. Here he is, based on his actual letters, explaining all this to Jack Telford:

‘Ah, yes. The warts. There were terrible things done at the beginning. Not just by the fascistas. And the fight for democracy? Of course. But democracy is the first victim of war. No? Hemingway could never bring himself to write about that. The need, sometimes, to suspend democracy, simply so it can live again. Those are warts, I think.’

‘It should be the task of journalists,’ said Jack, ‘to confront the uncomfortable. If we simply paint things in black, or white, we have no real credibility.’

‘I have an example,’ said the priest. ‘I was in Barcelona. In July. I read an article in The Times. About religious persecution in the Republican Zone. There is a British Jesuit. Burns. He writes these articles for them. About the six thousand priests killed here. But I wrote a letter to The Times. A response. And they printed my letter. I wrote that every priest killed in this terrible war has died because they were also politicians. Many of them were active members of political parties. Fascists. They had actively taken part in the distribution of anti-government propaganda. At the beginning, those priests paid a price for their political allegiance. As Socialists and Communists have done in the Nationalist Zone. Ignorant people, wicked people, took their revenge. Individuals. Yet not once – not once – have the Republican authorities issued orders for the persecution of priests, nor prohibited freedom of worship. And the fact is that Franco’s rebellion could never have started without the assistance of the Church. If there have been innocent victims, it is the Church itself that must carry the blame. And while the Republic’s government has never once sanctioned the murder of innocents, Franco does so every day of his life.’

The British Jesuit in question, was Tom Burns, who had indeed been schooled by the Jesuits. He was fanatically anti-communist and is the subject of a book, Papa Spy, written by his son, Jimmy Burns, as a tribute to the espionage undertaken by Burns Senior on behalf of the Allies during the Second World War. Tom Burns – and other prominent Catholics – played a big part in shaping British policy towards Spain. Policy that hardly did us credit!

Father Leocadio Lobo eventually went into voluntary exile in New York and died there in 1959. But the priest also serves to introduce Jack – and our readers – to several other key real-life Republican characters.

Just along the Gran Vía, at Number 31, on the corner of Calle Mesonero Romanos, stood the famous Café Zahara and its equally famous American Bar Miami. Next to it, the Doña Manolita lottery shop. Both premises were frequently shelled during the conflict.

He was glad to reach the Gran Vía, turned right past the Telefónica building – that soaring fortress tower – until he spotted the Café Zahara on the opposite side, the corner with Mesonero Romanos. A sheet of corrugated iron, rusted, daubed in scarlet painted slogans, covered one of its windows, but the place still smiled at him, modern and rationalist. Jack stopped, unsure whether to cross, uncertain whether he truly wanted to meet Father Lobo’s friends, and he glanced around, a moment of paranoia, to see whether he was observed.

Across the street, folk queued outside a small store, the ground floor of a building leaning against the Café Zahara’s flank. A lottery shop. Doña Manolita. Busy selling tickets for the big Christmas draw. To famine-eyed women. To their consumptive, emaciated children. To languid, shambling men. And Jack remembered the promise in the newspaper. Business as usual. Yet he began to wonder how a winner from this queue might spend their prize money. Share it across their neighbourhood? Purchase evacuation and freedom for their own family and those of friends? Feed the starving thousands? Or…

The air raid siren wound itself from bored beginnings to full-throated frenzy.

And those friends of Father Lobo? At the Zahara, Telford is introduced, for example, to Julián Besteiro. Born in 1870, he was a socialist politician who, in the final months of the war, tried to negotiate a peace settlement with Franco and the Nationalists. He would later contact Republican Colonel Segismundo Casado and, between them, they would help to launch an uprising against Negrín’s communist-dominated government. The uprising, early in March 1939, cost almost 2,000 lives but effectively brought an end to the Republic’s resistance and destroyed Negrín’s plans for a final stand in the Alicante Province. The socialist uprising helped to deliver victory for Franco. Besteiro’s reward? He was thrown in prison by Franco and died there in 1940.

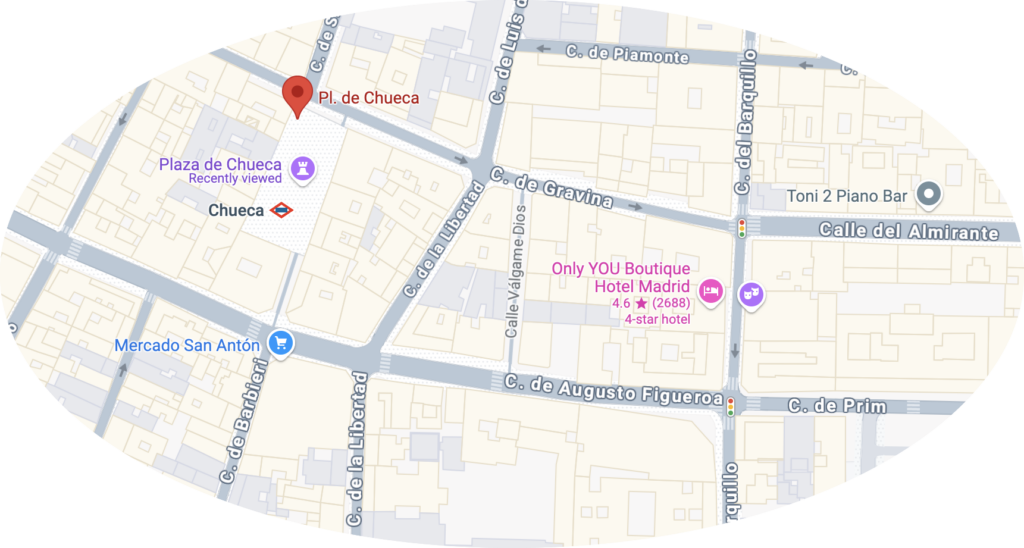

4. Plaza de Chueca

Anybody who knows Madrid really well, will know that the Plaza de Chueca has only really existed since 1943, when it was renamed (originally Plaza de San Gregorio) for the Spanish composer Federico Chueca. There was a famous flea market outside the San Antón church and, in the 1940s, this was replaced by an indoor market – itself eventually rebuilt and modernised to become the Mercado de San Antón that we know today.

Jack Telford, however, witnessed the barrio in a very different way.

Entire houses and apartment blocks collapsed along the Calle de Gravina and Hortaleza. And, ahead of him, a man was trying to flog the final spark of life from a spavined donkey hauling a cart of salvaged furniture. The fellow beat the beast with a fury that Jack could barely believe. All to no avail. For the poor creature faltered in its traces, took two last staggering steps, and collapsed. The carter still plied his whip but, by then, a pack of women and children had appeared on the road, as though by some gift of prescience, knives at the ready so that, by the time Jack had closed the distance, the man’s anger was dimmed to the weakest of protests. Blood mingled with the snow, ran into the gutter, and turned the street to a shambles of hacking, slicing and sawing.

I took the story from the many accounts of the starvation suffered by madrileños during the siege, and particularly from the remarkable book, El Hambre en el Madrid de la Guerra Civil (1936-39), by the sisters Laura and Carmen Gutierrez Rueda.

5. Plaza de las Salesas

At the south-east corner of the Plaza de las Salesas is the current Calle del Conde de Xiquena but, back in the 1930s, it was still called the Calle de las Salesas. On the corner, where the square meets the street, at Number 17, stood the old Café de las Salesas. The café closed, finally, in 1945. But it had been a popular destination for local writers and artists, with its red plush seats, its elegant waiters, and its wall-to-wall mirrors. It was a favourite with poet Antonio Machado and there’s a famous photo of him, meeting there with journalist and writer Rosario del Olmo, active in the Spanish Communist Party. Throughout the civil war, she was hugely prominent, and wrote for the anti-fascist journal, El Mono Azul (The Blue Overall) – among many other things. It was very much a symbol of working class resistance to fascism.

In the novel, Telford meets Rosario and others at the Café de las Salesas and, as they leave, somebody shoots at them:

Outside the café’s front door, their farewells were formal and somewhat frigid. But Jack was struck, once more, by the hush on tonight’s streets. Their voices echoed emptily between the buildings of the Plaza de las Salesas, and the streetlights still flickered. That warning again. And he was about to say his final goodbye when the door behind him crashed open.

They’d been attacked by a “fifth column” sniper, yet another regular hazard for any prominent Republican walking the streets during the siege. Paco snipers, as one of the characters calls them – Paco, of course, being the common short form, or nickname, for Francisco and, therefore, any supporters of Francisco Franco became Pacos.

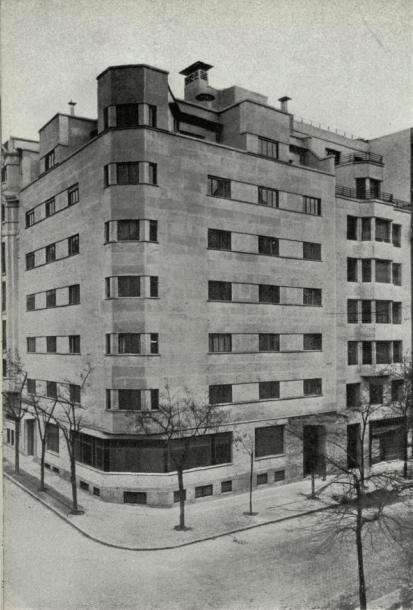

6. Calle Fernando el Santo

In the 1930s, the British Embassy in Madrid stood at Number 16, Calle Fernando el Santo, with the consular annexe alongside. The site is now occupied by a huge, circular block of apartments. It moved to its current location, in the Torre Espacio skyscraper in 2009. There’s a story I liked about how, early the war, the embassy received an instruction to paint a huge union jack on the roof, so that any bombers attacking Madrid would know that this was British property. Of course, in reality, it simply provided a neat crosshairs for aircraft bomb aimers. Here’s a photo…

And here was the result, as explained to Jack when he arrived there:

‘The blasted bomb came through just there,’ said the Consul. There was planking and stretched tarpaulin where finely moulded plaster relief decoration had once graced the classical ceiling. One of the walls had been recently rebuilt but not in character with the elegance, which Jack imagined the room must previously have possessed. ‘Straight down the centre of the Union Jack we’d taken so much trouble to paint on the roof. Germans, you know.’

‘Anybody hurt?’ Jack asked.

‘A disaster, Mister Telford. The chef, Fernando. Out of action for weeks afterwards. And poor Mrs Norris too. Need to introduce you, actually. Left her to do some digging when you arrived.’ He tapped the side of his Roman nose, led Jack out of the abandoned Embassy building itself and hurried across the windswept courtyard, past the guarded iron gates onto the Calle Fernando el Santo. ‘And hopefully there’ll be a cup of Rosie Lee waiting for us.’

7. Torrijos Market

At the time of writing, there’s been recent news that the Torrijos market in the Salamanca district has closed for good, having been taken over by a private-equity fund determined to “redevelop” the property.

But the market had a long history and, during the civil war, a prominent one. This is what the sisters, Laura and Carmen Gutierrez Rueda, tell us about what happened as money began to run out, and many families were obliged to barter their belongings:

People would go to the Torrijos market and exchange objects for food, supplies of which the unions tended to control: a sweater for a slice of bread. One of our aunts worked for a Swiss insurance company and was paid in cigarettes, which she would exchange for food.

And here’s Jack Telford, spending his wealth to buy luxuries that others had traded for food:

He’d bought the suit early that morning. Decent shoes too. From the Torrijos market, out beyond the Retiro. You could buy anything, the waiters at the Hotel Victoria had told him. Black market. Paid an absurd price. And Jack had not enquired too closely about the suit’s provenance.

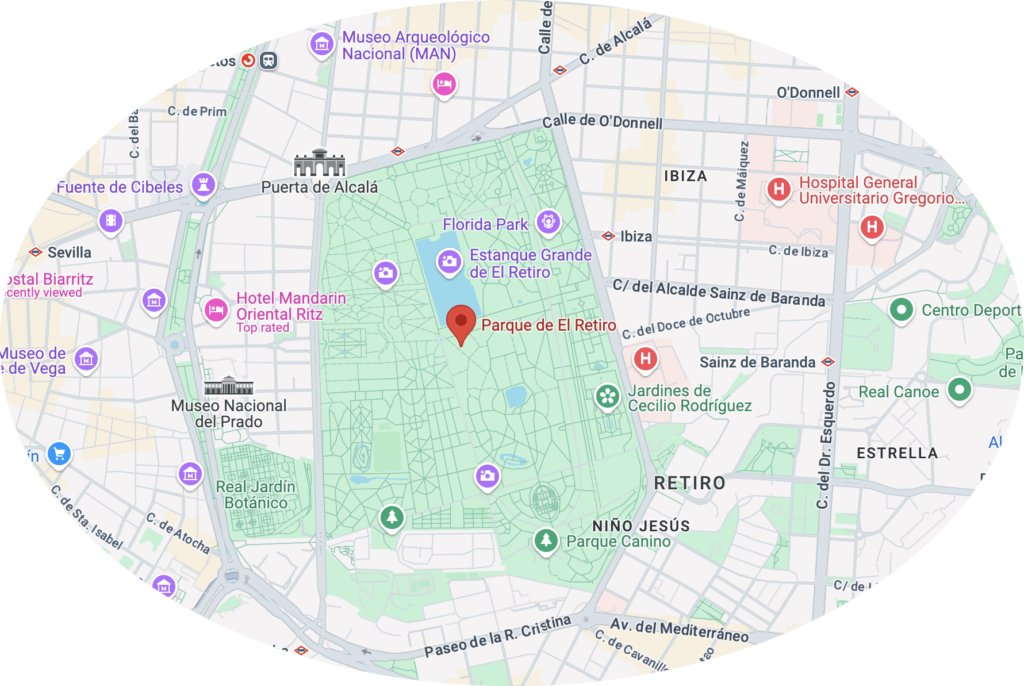

8. Retiro Park

There’s plenty to see and do at the Retiro Park, whether or not you’re doing this tour. Also known as Parque del Buen Retiro, it was originally the royal garden of the Buen Retiro Palace, a place of leisure and recreation for the Spanish monarchy in the 17th century, and opened to the public in 1868. The park’s history begins in the 16th century when the royal family had a retreat built on the site, which later evolved into the Buen Retiro Palace and its gardens. Built by King Philip IV, the Buen Retiro Palace served as a secondary residence and place of recreation for the royal family, hence its name “Buen Retiro” meaning “pleasant retreat”. Under the direction of the Count-Duke of Olivares, the palace and gardens were dramatically enlarged, with more than 20 buildings constructed between 1630 and 1660. After Queen Isabella II was overthrown in 1868, in Spain’s own Glorious Revolution, the park became publicly owned and open to the public. The park features a large boating lake, the Crystal Palace, numerous statues, and the Rosaleda (Rose Garden). In 2021, Buen Retiro Park became part of a combined UNESCO World Heritage Site that also includes Paseo del Prado.

The park, and its surrounding streets, feature in Until The Curtain Falls, of course. So, here are Jack and Ruby to pick up the story of the park, late in the siege of Madrid:

‘You should have been here before the war,’ she told him, peering through the iron railings. ‘But at least on this side, the trees still deaden it all. They hold back the war. ¡No pasarán! Not past the trees anyway.’

Jack had been astonished that there were still any left standing. And Ruby had patiently explained that the poor people of Madrid had, of course, wanted to cut down the Retiro’s trees. But the powers-that-be had stopped them. Closed the park. Appointed armed guards to protect it. Militiamen. They were still there. The guards. Though that hadn’t prevented the more desperate from their clandestine activities. Thousands of the trees had disappeared and now, blanketed in snow, shrouded in fog, it was somehow the saddest of Madrid’s ruins. But she hurried him onwards, down Menéndez Pelayo, past the writers’ houses. Because she thought he’d like to see them. The fascist author, Agustín de Foxá. And Sender’s place, where he wrote Míster Witt en el Cantón.

I included the mention of Ramón Sender and his hugely famous novel, Mister Witt en el Cantón, because it was a favourite of my close friend José García Quesada (Chamorro) who, sadly, did not live long enough to read Until The Curtain Falls.

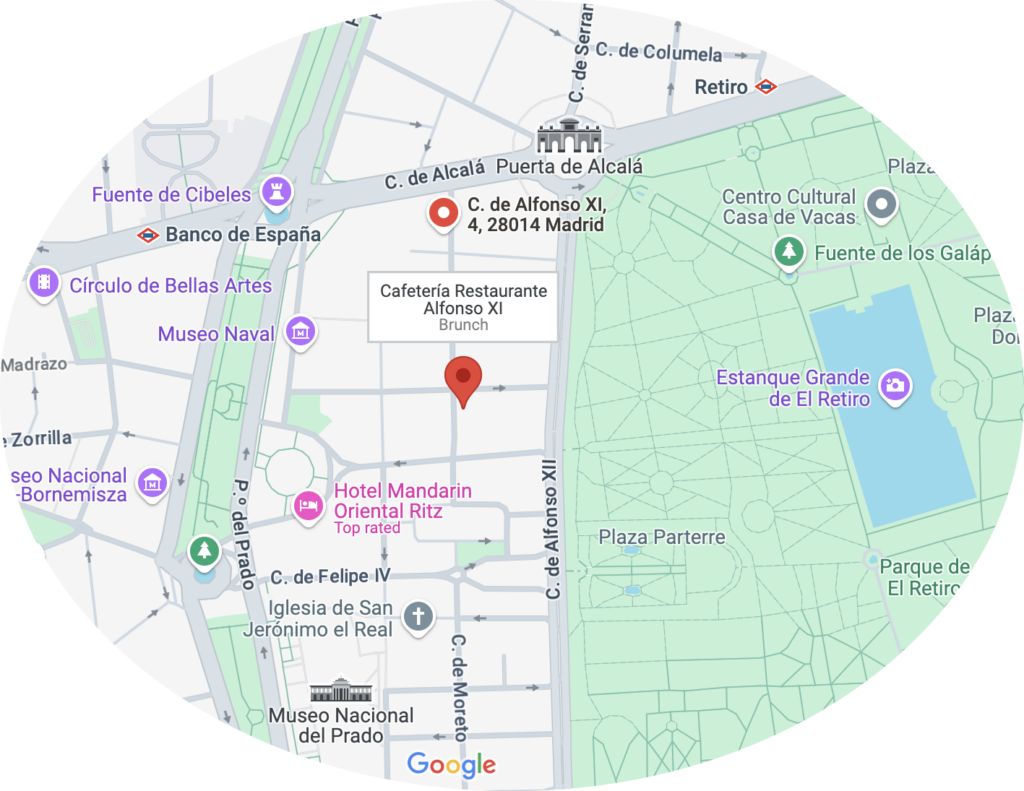

9. Gaylord Hotel, C/Alfonso XI, 3

The hotel stood at the north end of the street, at Number 3, where the MIO Group building now stands. But, during the war, the Gaylord was headquarters for the Soviet Russians in Madrid to support the Republic. It appears in the pages of Hemingway’s For Whom The Bell Tolls – and Hemingway certainly knew the place. In the novel, Robert Jordan, the main character, says that it was: “too good for a city under siege.”

In Until The Curtain Falls, I took this description from first-hand accounts I’d read:

It struck Jack that the Gaylord Hotel must be eminently suited to a Soviet propensity for intrigue and espionage. A discreet location, on a street with no traffic, Calle Alfonso XI, in a quiet but well-heeled district, yet very close to the Spanish War Ministry buildings, this latter, on the Plaza de Cibeles, heavily guarded, despite the Government itself no longer being in Madrid.

A couple of shaven-headed Slavic thugs, dressed like Chicago gangsters, stopped him just inside the opulent entrance, one of them carrying a machine gun very similar to the weapon Jack had used to take that second life. They frisked him, while Jack stared in wonder at the crystal chandeliers, the gold leaf worked into the oak panelling, the bas-relief semi-naked nymphs adorning the walls. It sounded like a party was in progress. Dance music drifted on cigar smoke. And he thought he heard champagne corks a-popping somewhere within.

The Soviet headquarters had a fearsome reputation, of course. It was closely associated with the arrest and assassination of Andreu Nin, leader of the POUM (Workers’ Party of Marxist Unification).

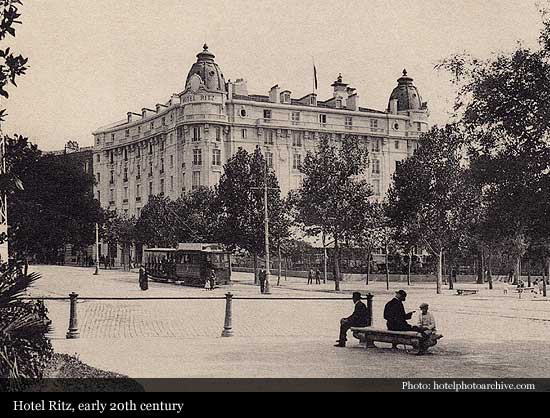

10. Plaza de la Lealtad

In the Plaza de la Lealtad, stands the Mandarin Oriental Ritz which, during the Spanish Civil War was simply the Hotel Ritz. It was built at the behest of King Alfonso XIII who, returning from a tour of Europe, realized that the Spanish Court lacked a hotel with enough pomp for European royalty and other illustrious visitors.

It served as a hospital for much of the conflict, and Telford comes here to visit his wounded friend, Capitán Fidel Constantino.

He turned his back on it all, followed the smoke until it rolled across Cibeles, with its sandbag bastions, then he turned right, along the Paseo, until the palatial grandeur of the Prado loomed ahead, and Jack swung left, to find the museum’s only marginally less ostentatious neighbour, the Hotel Ritz.

‘They say Mata Hari once stayed here,’ the Capitán told him.

Jack had found him, still weak from loss of blood, on a camp bed in the hotel’s former dance hall, surrounded by scores of others, sick and dying beneath the crystal chandeliers.

‘With a room of her own, I hope,’ he said.

The Capitán looked around.

‘It’s not so bad. Durruti died upstairs too. And I was here after Brunete. There were ten times this many.’ All the hospital stench of disinfectant, carbolic, human faeces, vomit, stale food, hit Jack at the same time. ‘Better now,’ the Capitán murmured. ‘Thanks to the Americans. Did you know Goff, English?’ Jack admitted that he did not. ‘Good man. One of the best. I was with him when we hit the Albarracín Bridge. Then Teruel. Carchuna too.’

It was, indeed, at the Ritz that Buenaventura Durruti died. The Spanish anarchist revolutionary had led his Durruti Column’s militiamen to Madrid in November 1936 to help with the defence but was shot, later that same month, during the fighting in the Casa de Campo. In the beginning, it was thought he’d been shot by an enemy sniper. But later research showed that he’d probably been hit by friendly fire. An accident. Yet, his death also spawned a host of conspiracy theories.

Mata Hari had, factually, stayed at the Ritz. In more recent years, guests included Hemingway, Grace Kelly, Ava Gardner, Michelle Pfeiffer, James Stewart, Madonna and more.

11. Plaza de Santa Ana

At the western end of the Calle del Prado is the Plaza de Santa Ana with, at its farthest corner, the ME Madrid Reina Victoria Hotel – opened in 1923 as the Gran Hotel Reina Victoria. It was Jack Telford’s home for most of the time he spent in Madrid. And he was in good company, since the well-known have always chosen to stay there – famous bullfighter Manolete, writer Ernest Hemingway, and actress Ava Gardner, among countless others.

Some of the bars in the square itself, like the Cervecería Alemana, were here during the Civil War and, just outside the hotel, is the statue Calderón de la Barca, distinguished poet and writer of Spain’s 17th Century Golden Age.

In the novel, a fair amount happens at the Reina Victoria, including Jack’s association with the famously Anarchist waiters. Here he is on Christmas Day, 1938:

Just another day to the Anarchist waiters. Although they had made an effort last night. Nochebuena, they had told him. Christmas Eve, even though they didn’t believe in all that religious nonsense. Yet a fish stew – improbable, but there it had been. And not bad. A small portion of turrón blando, too. And a few roasted chestnuts. Even a glass of sparkling wine. From Cataluña, they’d explained. Then apologised. There would be no more, of course. Not for a while, at least. Not until they’d taken back the two-hundred-mile-wide fascist corridor, which now divided the Republican Zones. Pure bravado. And Jack loved them for it.

12. Teatro Calderón

The Teatro Calderón was originally the Odeón Theatre, inaugurated in June 1917. It was later renamed after a performance of Calderón de la Barca’s El Astrólogo Fingido in 1927. The theatre continued to operate throughout the war and, in Until The Curtain Falls, became a favourite haunt for Telford and Ruby Waters:

Tarragona had fallen. Franco’s armies now less than fifty miles from Barcelona. And a profound silence had wrapped itself around the city in the ensuing seven days. But, at the Teatro Calderón, the matinée performance, it was hard to believe that anything was much amiss.

‘I don’t think I could bear to be here,’ said Ruby, during the intermission, ‘when Franco arrives in Madrid.’

They had already been entertained by the clown, Ramper; by a ventriloquist, the Yankee Balder; by tap dancers, Elsie and Waldo; and by the Republic’s very own “Shirley Temple”, Ana Mary. And there were still another dozen variety acts to come.

13. Plaza Mayor

The Plaza Mayor is a major public space in the heart of Madrid, the capital of Spain. It was once the centre of Old Madrid. It was first built (1580–1619) during the reign of Philip III. However, the current architecture dates from 1790 onwards, following a fire which consumed more than a third of the square. Prior to this, the buildings that enclosed the square were five stories, but the new architect, Juan de Villanueva, lowered the square’s surrounding buildings to three stories, closed the corners and created large entrances into the square itself.

In the novel, Jack Telford witnesses a food convoy arriving from Orihuela, near Alicante. He’s in company with Ruby Waters:

And, to Jack’s amazement, she wrapped herself around his arm, gave it a small hug as they followed the crowd and convoy up towards the Plaza Mayor. Torches had been lit in the square, and loudspeakers mounted on the back of a cart, blaring out scratchy recordings of the Republic’s many anthems, the volume set high enough to drown out the terminus traffic of the plaza’s incessant trams. Milicianos pushed and prodded some semblance of order upon starving citizens, almost driven mad by the crates of winter oranges, flagons of olive oil, sacks of salt, rice and potatoes driven here from the Vega Baja coastal district. Too little. Probably too late. But that didn’t matter much. Hungry hands stretched out for whatever small rations they could glean from this welcome but necessarily modest windfall.

Later, in the same chapter, Dolores Ibárruri joins the celebrations and makes one of her famous speeches to the crowd. Also known as La Pasionaria, of course (The Passionate One, or the Passion Flower, Dolores was a staunch Republican and member of the Spanish Communist Party. She is renowned for her slogan, ¡No Pasarán! (They Shall Not Pass!), which became a war cry for the defenders of Madrid. In March 1939, with the war lost, she flew into exile and could not return to Spain until 1977. She died in 1989.

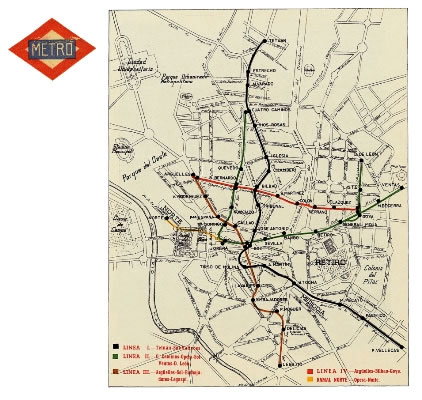

14. Metro Line 2

It’s worth a mention of the Madrid Metro system here, in a Spanish Civil War context. Like London, during the Blitz, the system became a symbol in its own right. By the 1930s, the Metro had expanded to include three lines and 32 stations, with construction continuing even during the Spanish Civil War, when the stations often served as bomb shelters. Here’s the way it looked in 1940:

And here’s Jack Telford:

For today he walked the shattered streets of the Argüelles district with Father Lobo, left him there on the Calle de la Princesa to say his Mass, and made his way down into the nearest Metro station at Santo Domingo on the Gran Vía. He bought a ticket for Banco de España. Twenty-five céntimos. Line Two. And an attractive clippie snipped his ticket at the barrier, directed him to the platform, direction Ventas.

The End

Leave a Reply