Jack Telford’s début came with The Assassin’s Mark, set towards the end of 1938. His second set of misadventures were detailed in Until the Curtain Falls, during the final months of the Spanish Civil War, early in 1939. Next, A Betrayal of Heroes follows Jack’s developing career as a war correspondent from 1939 until 1945. And, finally, the anthology of stories, Telford’s Odyssey (to be published in 2023) will variously see him at the Nuremberg Trials in 1946, in Berlin during 1948, in Suez with the 1956 crisis, in Israel for the 1967 Six Day War, in Lisbon during the 1974 Carnation Revolution – and perhaps a few more places in-between!

But, for now, and for readers who seem to have taken Jack to their hearts, here are a few details of Telford’s life which may have passed you by.

1. Jack’s Birthday

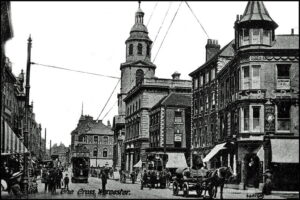

A boy, born in the early hours of Saturday 25th April 1908. Christened John Frederick three weeks later in the parish church of St. Paul’s, Worcester. The 1911 Census records show the family as living in Cecil Street, Worcester, a modest but comfortable home. His father, Frederick William Telford, was Head of Books at the Old Worcester Bank.

Worcester, 1908

And it was his father who insisted on dubbing him Jack, while his mother refused, to the end of her days, to ever call him anything but John. There was a sister, as well. Mary, two years older than Jack. His mother, Florence, was active in the Women’s Social and Political Union. Jack had an early memory of her returning bloodied from a rally, where she and her friends had been attacked by one of Worcester’s many anti-suffrage groups.

Worcester WSPU Activists

2. Jack’s Father

Florence Telford was also a staunch pacifist, and unhappy – she always told Jack afterwards – about the WSPU’s decision to abandon its campaigns when the war began in 1914. Jack remembered how, when his father had volunteered for the army, his departure hadn’t been tearful but, rather, an occasion for shouting and bitter recrimination. Florence Telford insisted, until the moment he left, that a real man would have stood his ground as a conscientious objector. Young Jack’s reasons for wanting his father to stay were, of course, entirely different. He clung, sobbing, to his father’s leg all the way to the garden gate.

Royal Field Artillery, 1915

Frederick Telford joined the Royal Field Artillery as a gunner. He wasn’t wounded but, late in 1915, he caught a chill and pneumonia set in. They sent him back to the Red Cross Hospital at St Albans, and there he died. The pneumonia, his mother had told him.

It was five or six years later when Jack discovered the truth. A visit to Salcombe to visit his mother’s family, and his cousin Betty, older than Jack, had revealed the shattering news that his father, recovered from the pneumonia, yet having escaped the war’s clutches and been sent home to St Albans, had taken his own life rather than face any prospect of return to the trenches.

The news – and his father’s ghost – would haunt Jack for many years to come.

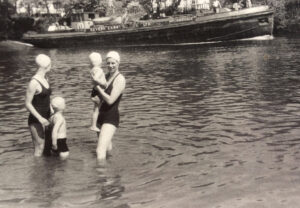

Grimley-on-Severn Lido, 1920s

3. The Swimming Lessons

Jack was taught to swim by his gran. She lived just outside Worcester, at Grimley-on-Severn. As a young boy, he spent chunks of the summer holidays with her, and it was his gran who took responsibility for teaching him to swim. After all, Grimley-on-Severn boasted one of the finest lidos in England. And she had a mantra: ‘Swimming,’ she would say, every time, ‘is the best form of exercise for both body and mind. Swimming in the sea is better than swimming in a pool. Swimming in a pool is better than no swimming at all.’

4. Jack Telford’s Schooldays

Jack was an unexceptional pupil at Elementary School, but he managed – against everybody’s expectations – to win a scholarship for Worcester Grammar School. And there, every day, he passed the school’s Roll of Honour. Ex-pupils who had fallen in the Great War. Telford F.W. 1894-1899. The daily reminder of his father’s tragedy. And, in Year Three, after Cousin Betty’s revelation, the tangled truth.

His School Certificate shows Jack having been examined in English Subjects (Group I), in Languages (Group II), and in Science and Mathematics (Group III) – and awarded passes with credit in English, History, French (Written and Oral), Biology, Geography and Art.

Worcester Grammar School, 1920s

Jack’s subsequent HSCE passes in English Language, English Literature and French, plus help from the University Grants Committee, were enough to gain him admission to the Owens College of Manchester University. With its strong links to the Mechanics’ Institute, the politics of the faculty were certainly Left-wing. Jack had been sucked into flirtations with various groupings. This was largely the result of his editorial responsibilities for the college magazine and, later, through his Presidency of the Esperanto Movement.

He graduated with a First Class Degree in History, and then gone to London University where he studied for a Diploma of Journalism, the only one then available in Britain.

5. A Career in Journalism

Jack Telford learned the practical side of his journalism the hard way. Freelance work for The Observer. They sent him to Germany in 1933 to cover Hitler’s rise to power and the Saar Plebiscite. Soon after, Jack found himself working for the Daily Mirror. In 1935 he worked alongside Sheila Grant Duff during the General Election campaign as she handled all the publicity for Hugh Dalton, the Labour Party’s spokesman on foreign affairs.

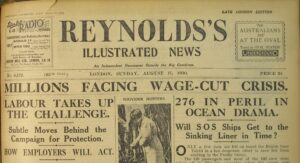

But Jack resigned from the Daily Mirror too when their anti-appeasement stance veered towards re-armament and a war-mongering editorial line. So he’d been doing freelance work again when Sheila introduced him to Sydney Elliott, the new editor for Reynold’s News. They took to each other straight away and Elliott had hired him in October 1937.

Reynold’s News, 1930 (Reynolds’s News, as it was before the name was updated)

It was Sydney Elliott, of course, who dispatched Jack to Spain in September 1938 to cover the story of Franco’s battlefield tours.

6. Jack’s Sister and Her Children

Sadly without a name in any of the novels, Jack’s sister Mary married Charlie Weaver in 1927. Charlie – whose bakery and confectionery shop stood on Friar Street, Worcester, until his death in the 1950s – was a good provider. By the time Jack was dispatched to Spain, in 1938, Mary and Charlie already had five small children, three girls and two boys.

7. His Mother’s Tragic Death

It had been feared, of course, that Jack had died in a drowning accident in San Sebastián. They might not have been close, but the news devastated his mother. And before the world discovered the truth, Florence Telford collapsed during a memorial service at All Saints in Worcester. She died in hospital a week later. To Jack, when he heard about it, it was sad, yet it also seemed strange. It had never occurred to him that his mother was even especially fond of him, let alone that she should be so overcome by grief at word of his death. Their relationship hadn’t offered much warmth, and Jack had only discovered the truth of his father’s suicide many years later – even then, not from his mother. She had pressed her pacifist views upon her son without once ever explaining the basis for her passion on that subject. So, after university, they had become even more distanced, his visits regulated. Diary commitments, rather than filial duty. Each second Thursday of the month.

8. Jack’s Reading Habits

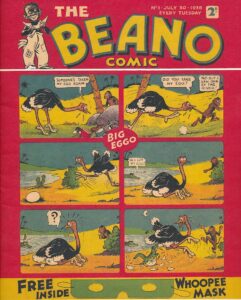

Jack’s journalism course had taught him that nobody can become a successful writer without also being a prolific reader. But that was no struggle. He’d grown up with The Tale of Mrs Tittlemouse or Peter and Wendy. In adolescence, he’d graduated to the novels of G.A. Henty, which fed his love of history. By the time he was sent to Spain, he was able to take two new publications with him. The Beano, its first issue published on 30 July 1938, and The Hobbit, which had been published in September 1937.

The Beano, Issue #1

From The Assassin’s Mark, we know that Jack was also a reader of Mark Twain, Thomas Jefferson, Chesterton, Oscar Wilde, Schopenhauer and Yeats. In Until the Curtain Falls, he borrows another Henty, Under Wellington’s Command. And through the pages of A Betrayal of Heroes, Jack manages to devour… Tolstoy’s Anna Karenina; Gogol’s Dead Souls; Gide’s Les Faux-monnayeurs; Charles Foleÿ’s Le Chasseur Nocturne; L’Étranger (The Outsider) by Albert Camus; Fortunata y Jacinta by Galdós; Ostrovsky’s How the Steel Was Tempered; Agatha Christie’s The Moving Finger; The Grapes of Wrath and The Pastures of Heaven, both by Steinbeck; and Saint-Exupéry’s The Little Prince. That’s a fair amount of reading – but then, the book does cover six years and 744 pages!

9. Jack’s Favourite Music

By 1979, Jack Telford was renowned for several reasons. As a result, he appeared on Desert Island Discs, on Sunday 8th September that year. An interesting interview with Roy Plumley, extracts of which you can find here… https://www.davidebsworth.com/telford-and-desert-island-discs.

John McCormack’s 1914 version of It’s a Long Way to Tipperary; Al Jolson and When the Red, Red Robin Comes Bob-Bob-Bobbin’ Along; the 1937 Voces Asturianas recording of ¡Ay, Carmela!: Josephine Baker singing J’Ai Deux Amours; Fats Domino and Blueberry Hill; Zeca Afonso and Grándola, Vila Morena; Jake Thackray and The Bull; and, finally, from La Bohême, Giuseppe di Stefano and Maria Callas singing O Soave Fanciulla.

Josephine Baker

But there are other accounts of Jack’s favourite music, as well. Here, from the Spanish Civil War: https://www.davidebsworth.com/spanish-civil-war-music-republican-spain. Here from the Second World War: https://www.davidebsworth.com/ten-top-hits. And here from the Portuguese Revolution: https://www.davidebsworth.com/portuguese-revolution-music-lisbon-labyrinth.

His friends made certain that the recording of O Soave Fanciulla was played at his funeral service in the church of St. Michael the Archangel, Lyme Regis. He had passed away, peacefully enough, in 1989 at his cottage on the edge of town, and is buried in the cemetery at Lyme where he had settled after – oh, but that’s another story.

Jack’s Final Resting Place

Leave a Reply