Readers have been asking me about the poetry in The Song-Sayer’s Lament and whether I wrote it myself. I always take such questions cautiously because, of course, you never quite know whether it’s loving or loathing that’s prompted the query. Anyway, hands up. Yes, I wrote it all.

But before I get to the poetry itself, maybe a few quick words of explanation.

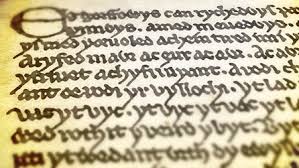

I wanted The Song-Sayer’s Lament to have an authentic 6th Century “feel”, but I was writing the story, in modern English – and English therefore stands for the Brythonic language, variations of which would have been spoken in that period by all those disparate but related clans, which most certainly did not think of themselves as “British” or “Welsh” or “Celtic”, but as separate peoples, tribes, linked (or possibly divided) by a common speech – the Cousins’ Tongue, as I have called it. And, because English substitutes here for that Cousins’ Tongue, it was important for me to make sure that place names, nicknames and individuals’ titles should convey in English those images that their original Brythonic names might have conjured up. In other words, I specifically chose not to use some form of pseudo-Welsh, for example, in place names. Welsh is a beautiful, lyrical but highly descriptive language, the rich simplicity of which would be totally lost for English-only readers who simply found themselves coming across locations like Gwynedd or Dinerth without knowing that these words convey something like the White-Wilds or Bear Fort respectively.

I wanted The Song-Sayer’s Lament to have an authentic 6th Century “feel”, but I was writing the story, in modern English – and English therefore stands for the Brythonic language, variations of which would have been spoken in that period by all those disparate but related clans, which most certainly did not think of themselves as “British” or “Welsh” or “Celtic”, but as separate peoples, tribes, linked (or possibly divided) by a common speech – the Cousins’ Tongue, as I have called it. And, because English substitutes here for that Cousins’ Tongue, it was important for me to make sure that place names, nicknames and individuals’ titles should convey in English those images that their original Brythonic names might have conjured up. In other words, I specifically chose not to use some form of pseudo-Welsh, for example, in place names. Welsh is a beautiful, lyrical but highly descriptive language, the rich simplicity of which would be totally lost for English-only readers who simply found themselves coming across locations like Gwynedd or Dinerth without knowing that these words convey something like the White-Wilds or Bear Fort respectively.

So poetry had to follow the same logic. In my story, the religious orders of non-Christian Britons are the Oak Seers – my anglicised version of Middle Welsh dryw, Latin druidae, Modern Welsh derw, etc, etc. The Oak Seers have various sub-groups, with differing responsibilities, and among those are the Song-Sayers – those responsible for keeping the old lore alive through their verbal records, their poetry. For my inadequate attempts to mimic some of the cadences that my Song-Sayers may have used, I went to the www.kernewegva site (A Guide to Welsh, Cornish and Breton Verse) and, whilst I’m not aware of any actual “Welsh” creation story surviving, I borrowed heavily from those Celtic tales told variously at www.historyarchive.whitetree.ca (Celtic Creation Story) and www.educationscotland.gov.uk (Celtic Creation Myth). I credited the resultant Song of the Great Melody to a fictional Tugri Iron-Brow, a potentially more realistic etymology of Taliesin. Here it is:

Hear now my tale of time before time. An endless sea’s Great Rhyme. Melody’s threads, creation’s chime.

Seas, in which a brine-foam creature’s born. Shapeless and free to roam, until she finds the oak-grove home.

Lonely, lost, she sups on milk-white seeds. Innocence flies, all gone, brings forth Kernuno, Hornèd One.

Kernuno, first child – lost, lonely too – grows to manhood, storm-tossed, seeds his mother’s brine-foam womb of frost.

She spawns them, gods of old. Epona. Teutates. Herne the Bold. Lug. Mapon. Taranis Storm-Cold.

The brine-foam creature flees – Senuna must go back to the seas, her Endless Song abandoned breeze.

Kernuno pines, love-lorn, ill at ease. Their child-gods pine and mourn, long for fresh invention. New dawn.

They take the oaken bark, chew the strips, then fashion boar, deer, lark, all creatures of both day and dark.

The seeds they scatter wide, forge woodlands, endless forest divide, through which the gods may hunt and ride.

But still they lack a plan, mould the bark. And then they fashion man. First woman too, the kinfolk clan.

The gods tire easily, mankind’s bane, to set contention free – cause strife, destroy harmony.

Their battles split the skies, fears in man. From Epona’s hooves, earth flies. Herne’s arrow falls. Fate dies.

Mapon strums his cruth, wakes melody, sings all Creation’s truth – deadly chords of endless youth.

Spears of Teutates blast earth. Lightning bolts falling fast, from fists of Taranis cast.

Where hoof or bolt cause strife, arrow fall strikes or spear blades knife, six more gods are given life.

Elder gods, in war, brought forth the new. Arawn and Brigid taught gifts of crafting, metals wrought.

Hunting, farming, fire-bright they gave you – Belenus, Lord of Light, and Morrigan, Bride of Night.

Yet, see this story clear. Remember, brave Danu, mighty Lir, brought to you a gift more dear.

Children twins. Cousin Folk. Danu’s Kin, from sun lands, ice broke, reaching homes of island oak.

While Lir’s sons, from the dawn, followed hard, found the second island, torn from the sea, fair and forlorn.

(Tugri Iron-Brow: Song of the Great Melody)

I worked out the forms by researching Early Medieval “Welsh” poetry, verse structures, rhythmic and rhyme patterns, etc. I picked three different patterns that I could use easily, one for Morgose the Song-Sayer, one for Tugri Iron-Brow, and one for other poets. So here is Morgose, singing The Lay of Lir – a legend/memory of how the ancients first discovered the lands they called the Isles of Fair Presence, the name that the early Greeks and Romans may have heard as Prydain and corrupted into Britannia.

rhyme patterns, etc. I picked three different patterns that I could use easily, one for Morgose the Song-Sayer, one for Tugri Iron-Brow, and one for other poets. So here is Morgose, singing The Lay of Lir – a legend/memory of how the ancients first discovered the lands they called the Isles of Fair Presence, the name that the early Greeks and Romans may have heard as Prydain and corrupted into Britannia.

Sweet water, I gave you, banished thirst. Children of the Lake Sea, your father set you free.

Mountains of rock I made to guard you, hold back the lake I laid. Walls of ebon and jade.

Yet no buttress can guard against fate, nor jealousies so great as Danu’s sister-hate.

Such hate may breach the wall, flood your world. So you must save it all, Deolu, straight and tall.

Deolu, favoured son, build the craft, complete the task undone, before the floods to run.

Carry all beasts aboard, start anew. Two by two shall reward the cautious husband’s hoard.

Twelve moons will wax and wane, voyage long, before land appears again. Great peaks arise through rain.

Isles of Fair Presence find. Name them so. Protect them for your kind. Leave jealousies behind.

Children of Lir, stand true. Never fail, nor falter in this view. Fair Presence lives through you.”

And here’s Morgose again, with a work of her own, a cryptic song, which will spin Ambros Skyhound’s own legend, aiming to build his reputation but, in the end, creating only enmity, jealousy and fear among his foes. This one is called Skyhound Rides the Whale-Road:

And here’s Morgose again, with a work of her own, a cryptic song, which will spin Ambros Skyhound’s own legend, aiming to build his reputation but, in the end, creating only enmity, jealousy and fear among his foes. This one is called Skyhound Rides the Whale-Road:

Spread our wings, wind-tasted, stowed the oars. Set course and bear the load. For Skyhound rides the whale-road.

Heave, lads. Haul. Salt-scented, goad the waves. Take fear, Sea Lord’s abode. For Skyhound rides the whale-road.

Brother-friend, foe-bender, showed the blade. Tremble, debts that are owed. For Skyhound rides the whale-road.

Three sails, three sows and three spears. Nine times nine, his crewmen’s fears. Who now past the maelstrom steers?

Sea-wings cry, Black Backs sweeping. Gannet soar, Red Beaks leaping. Wind-race pass, shoreline creeping.

What man guards the Lugos gate? Nine times nine their names must state, praise their talents, foes berate.

Lugos Silver-Hand commands, search the weathered wester-lands, where the blessèd cauldron stands.

Who has let the wolf-fang slip? Magnus Hard-Blade at his hip, Plucked from Iron-Anvil’s grip.

Where may Oak Seer giants rise? Above their own and others’ lies. Atone for flames and monks-hood cries.

What man guards the Lugos gate? Nine times nine their names must state, praise their talents, foes berate.

Chariot-Slayer, great Seer and Lord. To victories will steer – shades of Breiddon, doubly dear.

No quarter given. Revere no foes. Elm-Wood’s death song sounds clear, as Skyhound’s legions draw near.

Brother-friend, foe-bender, showed the blade. Tremble, debts that are owed. For Skyhound rides the whale-road.

Heave, lads. Haul. Salt-scented, goad the waves. Take fear, Sea Lord’s abode. For Skyhound rides the whale-road.

Spread our wings, wind-tasted, stowed the oars. Set course and bear the load. For Skyhound rides the whale-road.

This one is a different form, sung by a heretical young monk:

Summons the snow beast when the passes need to close, or tames the weather; frees those taken at the feast. Repays perfidy with fire.

And, finally, the essence of the novel itself, the conflict between myth and reality:

Myths, legends and lore, inspire our dreams, ambitions,

grant wings to heroes;

then turn, more potent than fact, beguile us, mislead, betray.

I always intended to run them past some “real” poets, but never managed to get round to it. So, they are what they are! And I hope, on balance, that readers like them.

Leave a Reply