Travel may broaden the mind – but it’s also essential as part of a writer’s research.

I’ve always had this writing rule. I try never to write about any of my major settings unless I’ve actually been there. But Covid made this impossible while I was working on A Betrayal of Heroes. So yes, normally we’d have found some way, Ann and myself, of making the journey to Morocco. In search of La Nueve, the company of Spaniards fighting for Free France. And we’d certainly also have followed the route of La Nueve and Leclerc’s 2nd Armoured Division. From Utah Beach and all the way to Strasbourg.

In between, we’d have headed to Pocklington in Yorkshire, where La Nueve was quartered before being sent to Normandy.

All impossible, of course. I had to rely on the eyes and ears and noses of other traveller friends and supporters to help me check. Did I have the colours, sounds and smells of all those places more or less correct? My editor Nicky Galliers was a good example. She knew the area around Fougères almost intimately. And, since there’s a fairly critical scene set there, her insight was invaluable. But there were dozens more (of you) who helped with similar experiences. Everywhere from Rabat to Cairo, from Écouché to Châtel-sur-Moselle.

Those “serendipity” moments of Travel Research are a gift!

But Pocklington? To be honest, and to my shame, I’d never even heard of Pocklington. Then, in a much earlier newsletter, some time last year, I happened to mention the town. I was deluged with incoming emails. It suddenly seemed I was the only person in the world who hadn’t, at some stage, worked there, or grown up there, or had their first romance there, or knew somebody who knew somebody… Well, you get the picture.

I therefore had plenty of help checking out a few basics. But, naturally, A Betrayal of Heroes had to go to print still without me being in Pocklington in person.

Better late than never, however, we set off a few weeks ago to check out the place. We stayed at the wonderful Carpenter’s College on Union Street. There, during the war, Mister Humble would certainly have sold milk and cheese to the Spanish boys. We spent several happy hours at the Feathers Hotel, which features in the extract I’ve been reading out during the novel’s launch events. There’s a PDF copy of the extract available if anybody wants it. And we wanted to find the United Services Club, outside of which this photo of La Nueve and their French captain, Raymond Dronne, was taken.

Sometimes, such visits are a bit strange. In this case, with only this photo as a basis, I’d decided to set another important scene in the United Services Club. It’s the scene in which Dronne and his men find out, over the radio, that D-Day has happened. And it’s happened without them. In practice, Leclerc’s units were only sent to Normandy on 1st August 1944. They weren’t happy about it. So, I imagined Dronne and a few of the Spaniards in an upstairs room of the United Services Club, playing snooker, annoying paintings of the Battle of Waterloo on the walls.

And this is what I call serendipity. We were wandering around Pocklington just after we’d arrived and I stopped a man, at random, on the street.

‘Excuse me,’ I said. ‘Do you know where the United Services Club might be?’

‘Well, I should,’ he replied. ‘I’m the Secretary.’

And he took us there.

‘I don’t suppose,’ I said, ‘that you have a snooker table.’

‘Of course. There’s always been a snooker table at the Club.’

‘During the war?’

‘Certainly.’

‘Upstairs?’ I said.

‘How did you know?’ he laughed. ‘Let me show you.’

It was precisely as I’d imagined the room. Even the faded marks on the walls where a couple of paintings had once hung. Paintings of Waterloo? Yes, of course. This had, as I already knew, once been the Waterloo Hotel, named in honour of the battle. And yes, there’d once, long ago, been prints of Hollingford’s and Heath’s Waterloo battlefield pictures.

Strange. But fairly typical of the way in which travel is such an important research tool for writers. It was an early lesson for me when I was working on my very first novel, The Jacobites’ Apprentice.

Travel Research can help you see or hear things historians may have missed.

In 1745, the Welsh Jacobite supporters of Bonnie Prince Charlie met and plotted in the Wrexham hotel now called the Wynnstay Arms. Back then, it was the Eagles Hotel. The interior has changed dramatically. But gazing from the area where those plotters dined, out onto the town’s High Street, I knew exactly how it would have looked in 1745. And the scene almost wrote itself. For me, there’s no question about it, being in situ simply helps me write.

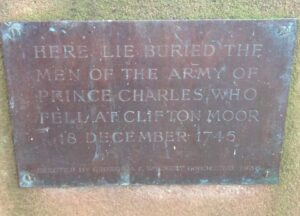

The Jacobites’ Apprentice also caused me to visit the site in Cumbria where the last battle on English soil was fought. Of course, I’m ignoring here the very real but one-sided battles at Peterloo in 1819. Or the various attacks against strikers, for example, in Liverpool during August 1911. And at Orgreave during the Miners’ Strike in 1984. No, I’m talking about the Battle of Clifton Moor, December 1745. I’d read several accounts of the battle but couldn’t quite picture it from the description.

It was fought almost in pitch darkness. Over a cluster of small and steeply sloping enclosed fields, through hedgerows and ditches. And it was only by walking the ground that I felt able to describe the skirmish with any credibility.

My second novel was The Assassin’s Mark. It’s been described as Homage to Catalonia meets Murder on the Orient Express. It follows the real-life battlefield bus tours organised by Franco while the Spanish Civil War was still raging. I was lucky enough to have the precise itinerary for the tours. These took place from July 1938 until June 1945. Along Spain’s northern coast. Fabulous!

The main roads of 1938 are now narrow back roads, rarely used. But perfectly serviceable, if somewhat tortuous. More remarkable? Most of the hotels used by the tour groups are still there. And still operating, as well. There were sights and sounds and smells while making this trip that I’d never have been able to include in the story without doing it myself. One of my happier moments came when an American couple wrote to me. They said they’d been planning a trip to northern Spain. Then they came across The Assassin’s Mark and followed it, chapter by chapter, along the route.

There’s nothing like Travel Research to give you a new perspective on an old story.

Our next adventure was in November 2013. I was planning to write The Kraals of Ulundi, set during the second half of the 1879 Zulu War. It tells the story of the conflict from the point at which Michael Caine left off in the movie, Zulu. The Zulu War has a huge following. It’s been the subject of many, many non-fiction history books. Zulu War battlefields have been mapped and described over and over again. So, was it worth a trip all the way to KwaZulu-Natal simply to check it out? Hell, yes. One of the best journeys we’ve ever made. And all those historians may have been brilliant at describing the sights and smells. But not one of them – not one – had ever written about KwaZulu-Natal’s ubiquitous Hadeda Ibis, the raucous cry of which follows travellers all over the region, as it would have done in 1879.

So, this…

Shaba reached kwaMbonambi after four days of continuous pain, hoping to find induna Mnukwa and the rest of his Scout Swarm. But he found there only the smoke-stained songs of mourning, winging on the wind like the harsh cry of the hadeda bird. The scorched wreckage of wattle, thatch and palisade. The ruin of warriors, walking or crippled. The barest remnant of families, fatherless infants and weeping widows.

Next, to 1815, and Napoleon’s Waterloo Campaign. The Last Campaign of Marianne Tambour tells the story from a French perspective. But specifically from the viewpoint of two French women in the thick of the fighting. Based on real-life characters again. We visited the area in June 2015 for the Bicentenary Commemorations. 6,000 brave souls recreated the battle itself. Only a fraction of the roughly 200,000 soldiers who actually took part, but still an astonishing re-enactment.

Travel Research, at its most simple, provides inspiration to writers.

Once again, one of the battlefields – at Gilly, just outside Charleroi – would have been hard to describe without being there. And walking the ground of Waterloo itself let me see exactly what my characters would have been able to see. The re-enactment gave me a scale for the noise, the chaos and the smoke. The bivouac areas for the participants gave me a clue to just how big the real French encampments must have been. All invaluable.

In the same way, I’d struggled to write some of the scenes for Until the Curtain Falls, my second Jack Telford novel. These were the scenes set in Albacete, Spain. It’s a city that’s changed enormously since 1938. But I met a local historian there with a rare set of old photographs. A man who also knew exactly how each of the bars and hotels had looked at the time. In one of those hotels, I found exactly the inspiration I needed to finish the story.

Finally? It was entirely different circumstances that stopped us visiting modern Chennai, old Madras, for the first part of my Yale Trilogy. The Doubtful Diaries of Wicked Mistress Yale is set there. But I found a wealth of contemporary travellers’ accounts. In addition, I was lucky to stumble on the Madras Literary Society. Their members, more local historians, helped me correct an early draft. So that, hopefully, reading the book will transport readers back realistically to Madras in 1672.

And where next? A Betrayal of Heroes may already be published, but that won’t stop us. In the not-too-distant future, Morocco. And that route of the 2nd Armoured Division, from Normandy to Strasbourg. After that, probably Berlin for a work-in-progress further Jack Telford story. Well, why not? Somebody’s got to make these sacrifices.

The noisy Hadeda Ibis

The noisy Hadeda Ibis

Leave a Reply