I always check out the locations for all of my novels and have never yet failed to make positive changes to the text as a result. So, early in September 2014, I drove to France and Belgium with Ann so that we could travel the routes followed by Marianne Tambour and Liberté Dumont in the novel, though the Waterloo Campaign. While doing so, it occurred to me that this is a much more logical way of seeing the sites and battlefields associated with the Hundred Days than the more “traditional” option of beginning in Brussels. It also follows, more or less, the route signposted at regular intervals by La Route Napoléon en Wallonie, a development by the Belgian Tourist Board. We used Namur as a base and adopted the itinerary listed below, but it’s just as easy to reverse or change the order.

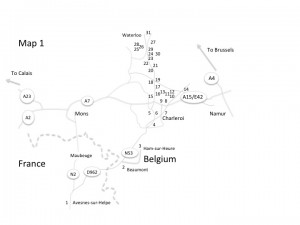

Please remember, though, that the following maps are intended for guidance only, rather than accurate navigation.

Map 1 (Overview)

Day One

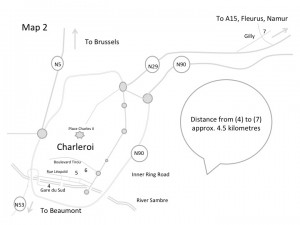

Map 2 (Charleroi and Gilly)

We drove from Calais, through Dunkerque, Lille, Valenciennes and Maubeuge to Avesnes-sur-Helpe (1) and the former residence of the local Prefect (next to the impressive St. Nicolas Church and down the alley at the side of the Tourist Office) where a plaque marks both the overnight stop that Bonaparte made there on 13th June 1815 as well as the visit by the Emperor’s great-nephew, Louis Napoleon, at the end of August 1870 before his own exile to England and subsequent death in Zululand. Then 30km northeast, along the D962 through Hestrud to Beaumont (2), now in Belgium but, in 1815, just on the French side of the border. The Emperor spent the next night (14th June) at the current town hall, while the Imperial Guard was bivouacked in the town itself and in the area immediately to the south. Continuing northeast, you can follow the lanes to Ham-sur-Heure (3) where Bonaparte dozed at the crossroads while the army marched past, or take the N53 straight to Charleroi. These are all lovely locations and deserve some exploration. But the next stage, through Charleroi itself, requires a fair bit of imagination. The bridge where the French drove back the Prussians is no longer there and even the Sambre river itself has been diverted but, at the Gare du Sud railway station (4), there’s a Drum Memorial to those who fought here in 1815

We drove from Calais, through Dunkerque, Lille, Valenciennes and Maubeuge to Avesnes-sur-Helpe (1) and the former residence of the local Prefect (next to the impressive St. Nicolas Church and down the alley at the side of the Tourist Office) where a plaque marks both the overnight stop that Bonaparte made there on 13th June 1815 as well as the visit by the Emperor’s great-nephew, Louis Napoleon, at the end of August 1870 before his own exile to England and subsequent death in Zululand. Then 30km northeast, along the D962 through Hestrud to Beaumont (2), now in Belgium but, in 1815, just on the French side of the border. The Emperor spent the next night (14th June) at the current town hall, while the Imperial Guard was bivouacked in the town itself and in the area immediately to the south. Continuing northeast, you can follow the lanes to Ham-sur-Heure (3) where Bonaparte dozed at the crossroads while the army marched past, or take the N53 straight to Charleroi. These are all lovely locations and deserve some exploration. But the next stage, through Charleroi itself, requires a fair bit of imagination. The bridge where the French drove back the Prussians is no longer there and even the Sambre river itself has been diverted but, at the Gare du Sud railway station (4), there’s a Drum Memorial to those who fought here in 1815  and, just across the new bridge, the Banque Nationale building (5) stands on the site of the Puissant house where the Emperor spent the night of 15th June. Two streets further on, at 88 Boulevard Tirou (6), is the house where General Letort was treated and died after Gilly. And so, on to Gilly itself (7), along the busy N29. Gilly is now a mere suburb of Charleroi, but we looked out for the church, just to the left, off the main road where it begins to dip down into the valley, and stopped there to look across at the steeply sloping high ground opposite, where the Prussians took up their positions for the battle on 15th June. Then we continued along the N29, climbing up the hill towards Fleurus and past the Abbey of Soleilmont (also on the left), still surrounded by woodland, as it was in 1815, when it anchored the right of the Prussian line. We ended the first day by following the road almost as far as Fleurus but turned east on the E42/A15 for a comfortable night and good food in Namur.

and, just across the new bridge, the Banque Nationale building (5) stands on the site of the Puissant house where the Emperor spent the night of 15th June. Two streets further on, at 88 Boulevard Tirou (6), is the house where General Letort was treated and died after Gilly. And so, on to Gilly itself (7), along the busy N29. Gilly is now a mere suburb of Charleroi, but we looked out for the church, just to the left, off the main road where it begins to dip down into the valley, and stopped there to look across at the steeply sloping high ground opposite, where the Prussians took up their positions for the battle on 15th June. Then we continued along the N29, climbing up the hill towards Fleurus and past the Abbey of Soleilmont (also on the left), still surrounded by woodland, as it was in 1815, when it anchored the right of the Prussian line. We ended the first day by following the road almost as far as Fleurus but turned east on the E42/A15 for a comfortable night and good food in Namur.

Day Two

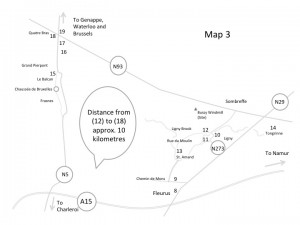

Map 3 (Fleurus, Ligny and Quatre Bras)

Retracing our steps along the E42, we began today in Fleurus where, on 16th June, Bonaparte’s Central Column, Reserve and Right Wing had marched in an effort to bring the Prussians to a more decisive battle. On the left of the N29 (opposite a Ford dealership) stands the monument (8) at the  Naveau windmill, which Napoleon used as an observation post before the battle at Ligny. The Naveau monument actually commemorates three French victories on this ground, in 1690, 1794 and 1815. Further on, at the very edge of town, left along the Mons road, is the Chateau de la Paix (9), which served as Bonaparte’s headquarters until the following morning. From here you can either follow the Route Napoléon signs, leading to St. Amand and giving a good view of the whole battlefield, a panorama of Wagnelée, St Amand, Ligny and Tongrinne – the villages in and behind which Blücher had drawn up his army. Alternatively, you can carry on up the N29 and then turn left towards Ligny on the N273. As you drive through Ligny, there is a road signposted St. Amand, to the left (at a large cannon barrel memorial of the bicentenary) with a car park next to the Farm d’En Haut and opposite the church (12). A sign at the church will lead you to the Farm d’En Bas (11) – both church and farm have been rebuilt since the battle but each was the site of horrific hand-to-hand fighting. Back on the N273, at the north end of the village, is the Centre Genéral Gérard Museum (10) – open most days but only afternoons – with its wonderful collection and large-scale map of the battlefield. There was plenty more to see around Ligny, and particularly the neighbouring villages of St. Amand (13) and Tongrinne (14) where, from the original church, you can get a good impression of this section’s terrain. The sloping ground north of Ligny, along the N93, from which Blücher commanded his forces, also marks the line of the Prussian retreat towards Wavre and the area where the Imperial Guard later rested.

Naveau windmill, which Napoleon used as an observation post before the battle at Ligny. The Naveau monument actually commemorates three French victories on this ground, in 1690, 1794 and 1815. Further on, at the very edge of town, left along the Mons road, is the Chateau de la Paix (9), which served as Bonaparte’s headquarters until the following morning. From here you can either follow the Route Napoléon signs, leading to St. Amand and giving a good view of the whole battlefield, a panorama of Wagnelée, St Amand, Ligny and Tongrinne – the villages in and behind which Blücher had drawn up his army. Alternatively, you can carry on up the N29 and then turn left towards Ligny on the N273. As you drive through Ligny, there is a road signposted St. Amand, to the left (at a large cannon barrel memorial of the bicentenary) with a car park next to the Farm d’En Haut and opposite the church (12). A sign at the church will lead you to the Farm d’En Bas (11) – both church and farm have been rebuilt since the battle but each was the site of horrific hand-to-hand fighting. Back on the N273, at the north end of the village, is the Centre Genéral Gérard Museum (10) – open most days but only afternoons – with its wonderful collection and large-scale map of the battlefield. There was plenty more to see around Ligny, and particularly the neighbouring villages of St. Amand (13) and Tongrinne (14) where, from the original church, you can get a good impression of this section’s terrain. The sloping ground north of Ligny, along the N93, from which Blücher commanded his forces, also marks the line of the Prussian retreat towards Wavre and the area where the Imperial Guard later rested.

In the early afternoon, however, we headed back towards Charleroi, looking for the N5, which would lead us to Frasnes on the roads followed by Marshal Ney, with the French Left Wing, who had been instructed to take the village of Quatre Bras and keep Wellington’s army in that area from joining with the Prussians. Ney had already been held up, just north of Frasnes, by stubborn resistance from Dutch-Belgian and Nassauer units. So we started there, vainly looking for the suburb of Le Balcan (15). Roadworks and poor signage thwarted us here, but we managed to find the site of the Grand Pierpont Farm and, to the right, the L’Erâle Farm – between which the Netherlanders established and held a thin line against Ney’s forces with such determination that he was convinced he faced the whole of Wellington’s army. The Dutch-Belgians were eventually pushed back to the Gémioncourt Farm (16), which has changed little since 1815. A plaque on the  farm’s wall apparently marks the severity of the fighting, both here and across the Gémioncourt Brook that ran beyond, but at the time of our visit there were unfriendly “Private Property” signs everywhere, though we took some good photos from the roadside. From Gémioncourt, the road passes two monuments, one of them to the Duke of Brunswick (17), and these also mark areas of heavy fighting, where Wellington’s squares turned back the French cavalry, though at considerable cost to themselves. There are more memorials in Quatre Bras (18) itself, and the old farmhouse (19) still stands at the crossroads, though in the middle of a major refurbishment.

farm’s wall apparently marks the severity of the fighting, both here and across the Gémioncourt Brook that ran beyond, but at the time of our visit there were unfriendly “Private Property” signs everywhere, though we took some good photos from the roadside. From Gémioncourt, the road passes two monuments, one of them to the Duke of Brunswick (17), and these also mark areas of heavy fighting, where Wellington’s squares turned back the French cavalry, though at considerable cost to themselves. There are more memorials in Quatre Bras (18) itself, and the old farmhouse (19) still stands at the crossroads, though in the middle of a major refurbishment.

The evening took us further north on the N5 but turning off for the centre of Genappe, parking next to the Carrefour supermarket, then up and across the Dyle bridge to find the site of the former King of Spain Inn (20) – along the main street, past the square and church, in the Place de l’Empereur – where Wellington stayed on 16th June and Blücher spent the night after the battle. Immediately north of the centre, before rejoining the bypass and heading back to Namur, is the ground (21) on which Napoleon and his cavalry made a final attempt to overtake Wellington’s rear-guard as the Duke’s forces fell back from Quatre Bras towards the ridge of Mont St. Jean. It was here that the pursuit petered out and set the scene for the following day’s monumental confrontation.

Day Three

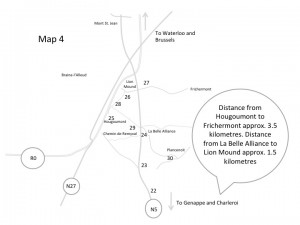

Map 4 (Le Caillou, Rosomme, Mont St. Jean, Plancenoit and Waterloo)

The Waterloo battlefield is relatively compact, but it’s still best to visit the main viewing points in some sort of logical order, though bearing in mind that parking is either limited or even non-existent at some of those locations. In our case this was fairly easy since we were following in the footsteps of Marianne Tambour and Liberté Dumont, so we drove from Namur back to Quatre Bras on the N93, broadly along the route taken by Bonaparte’s Central Column and Reserve in order to catch up with Ney’s Left Wing. Grouchy and the 33,000 men of the Right Wing, of course, had been sent off to pursue the Prussians. So, Quatre Bras and Genappe again, then to the Pebble Farm – Le Caillou (22) – where the Emperor spent the night of 17th June. There is a great little museum in the old farmhouse, which is well worth a visit, and includes the Emperor’s campaign cot. About 1 kilometre north of Le Caillou on the N5 is Rosomme (23), around which the Imperial Guard was assembled and where Bonaparte spent a chunk of the 18th, though unable to see a great deal of the action. As it happens, it’s virtually impossible to spot the place, which is now surrounded by high hedges. But if you get to the Victor Hugo monument without noticing it, you’ve gone too far! And, beyond Rosomme, the farm/inn called La Belle Alliance, or the Beautiful Alliance (24), from which the Emperor reviewed his army at 11.00am on the morning of the battle, and to which he returned only late in the day, even though it was the obvious place from which to command the attacks. There is a viewpoint here, marked by a plaque on the right side of the lane that leads to Plancenoit. The N5 is a very busy road, by the way, so you need to be careful here.

old farmhouse, which is well worth a visit, and includes the Emperor’s campaign cot. About 1 kilometre north of Le Caillou on the N5 is Rosomme (23), around which the Imperial Guard was assembled and where Bonaparte spent a chunk of the 18th, though unable to see a great deal of the action. As it happens, it’s virtually impossible to spot the place, which is now surrounded by high hedges. But if you get to the Victor Hugo monument without noticing it, you’ve gone too far! And, beyond Rosomme, the farm/inn called La Belle Alliance, or the Beautiful Alliance (24), from which the Emperor reviewed his army at 11.00am on the morning of the battle, and to which he returned only late in the day, even though it was the obvious place from which to command the attacks. There is a viewpoint here, marked by a plaque on the right side of the lane that leads to Plancenoit. The N5 is a very busy road, by the way, so you need to be careful here.

Just to the south, off the N5, a lane (the Chemin de Remyval) runs westwards, and we walked two hundred yards along this track to roughly the position in which Kellerman’s cavalry were deployed and from which Liberté would have seen the opening action of the battle, the attack on the Hougoumont Farm (25), hidden in 1815 among trees opposite, at about 11.30am. This was supposed to be a diversion, but the farm, its gardens and orchards, remained the scene of horrific  fighting and burning barns until late in the evening. We walked back to La Belle Alliance and drove on up the N5, turning left to the Lion Mound (26). Needless to say, neither the mound nor the buildings were here in 1815. But in the Visitors’ Centre, at the foot of the Mound, there’s an excellent audio-visual presentation while, in the adjacent building, there’s the dramatic and not-to-be-missed Panorama. We then climbed to the top of the hill (226 steps), from which the whole battlefield can now be surveyed. It stands almost in the middle of Wellington’s line, which ran along the track and low ridge immediately behind the Mound and the road away to the east. Across the shallow valley, to the south, is the opposing and equally modest ridge along which the Emperor drew up his own forces. Looking that way, we could see the rooftops of Hougoumont ahead (to our right) and, just to our left, the farm at La Haye Sainte on the Charleroi-Brussels road (N5), which was captured by the French though only late in the day. But it was easy to picture the three main French attacks from here. First, the valley filling with Bonaparte’s advancing infantry battalions on the far side of the N5, turned back by Wellington’s own infantry on the East Ridge and then pursued by the British cavalry counter-attack. Second, the massed ranks of the French cavalry coming almost straight towards our current position, wave after wave for almost two hours, only to be dashed against the Allied squares. And, third, the proud regiments of the Imperial Guard marching to their doom also on this same ground.

fighting and burning barns until late in the evening. We walked back to La Belle Alliance and drove on up the N5, turning left to the Lion Mound (26). Needless to say, neither the mound nor the buildings were here in 1815. But in the Visitors’ Centre, at the foot of the Mound, there’s an excellent audio-visual presentation while, in the adjacent building, there’s the dramatic and not-to-be-missed Panorama. We then climbed to the top of the hill (226 steps), from which the whole battlefield can now be surveyed. It stands almost in the middle of Wellington’s line, which ran along the track and low ridge immediately behind the Mound and the road away to the east. Across the shallow valley, to the south, is the opposing and equally modest ridge along which the Emperor drew up his own forces. Looking that way, we could see the rooftops of Hougoumont ahead (to our right) and, just to our left, the farm at La Haye Sainte on the Charleroi-Brussels road (N5), which was captured by the French though only late in the day. But it was easy to picture the three main French attacks from here. First, the valley filling with Bonaparte’s advancing infantry battalions on the far side of the N5, turned back by Wellington’s own infantry on the East Ridge and then pursued by the British cavalry counter-attack. Second, the massed ranks of the French cavalry coming almost straight towards our current position, wave after wave for almost two hours, only to be dashed against the Allied squares. And, third, the proud regiments of the Imperial Guard marching to their doom also on this same ground.

In a way, there was no need to view the site from anywhere else, but I wanted to see the terrain from the perspective of those taking part. So we headed for the Viewpoint on the East Ridge (27). As we walked along the lane in that direction, from the Mound, we had to remember that, in 1815, there would have been a high bank to our right (the earth was removed to make the hill) so that the road passed through a cutting. But, when you come to the crossroads with the N5 (there’s a  memorial to Lieutenant Colonel Gordon just down the main road from here) and continue, the terrain is much more recognisable as it would have been on the day of the battle. Two hundred yards further took us to the Viewpoint, at the heart of the positions in which the British Rifle Brigade and Picton’s Division stood, and from where they would have seen the French Grand Battery’s 80 big guns wheeled into line on the opposite ridge before opening their bombardment at 1.30pm. This is where those battalions held back three huge phalanxes of Count d’Erlon’s French infantry, over 10,000 of them, before Sir William Ponsonby’s Union Brigade with their Scots Greys came up at the gallop to chase off the enemy, but then continued too far and were ripped to shreds in their turn by French Lancers coming up on their flank. The whole thing took no more than half an hour and left the valley’s trampled crops strewn with corpses. It was from this direction, too, that the bulk of Blücher’s Prussians arrived in time to save the day, later in the evening.

memorial to Lieutenant Colonel Gordon just down the main road from here) and continue, the terrain is much more recognisable as it would have been on the day of the battle. Two hundred yards further took us to the Viewpoint, at the heart of the positions in which the British Rifle Brigade and Picton’s Division stood, and from where they would have seen the French Grand Battery’s 80 big guns wheeled into line on the opposite ridge before opening their bombardment at 1.30pm. This is where those battalions held back three huge phalanxes of Count d’Erlon’s French infantry, over 10,000 of them, before Sir William Ponsonby’s Union Brigade with their Scots Greys came up at the gallop to chase off the enemy, but then continued too far and were ripped to shreds in their turn by French Lancers coming up on their flank. The whole thing took no more than half an hour and left the valley’s trampled crops strewn with corpses. It was from this direction, too, that the bulk of Blücher’s Prussians arrived in time to save the day, later in the evening.

But what about the West Ridge? There is a Viewpoint here (28), back towards Hougoumont, past the Lion Mound. But at the time of writing and our visit, there were large-scale building projects taking place in preparation for the bicentenary events, which prevented access to that section of the ridge. Yet you can normally look down into the valley from here, picturing the scene from about 4.00pm onwards as the French cavalry began to form up, 500 horsemen abreast and 12 ranks deep, then coming forward at a slow trot, up and over the ridge, swarming around the Allied squares  lined along the lower ground behind, but unable to break them. The French fell back down the slope to regroup, to attack again and again, perhaps ten times over the next hour and a half, before finally giving up on the stalemate. But at 7.30pm, the now critically stretched British position here was attacked once more – this time by Bonaparte’s Imperial Guard Foot Chasseurs and Grenadiers, his élite troops. Wellington kept his own thin lines, his own guardsmen, concealed until the last possible moment but then raked the advancing Frenchmen with musket and case shot. Many of the Imperial Guard battalions were torn apart, and the rest fell back towards La Belle Alliance. The Guard was defeated and Wellington signalled a general advance.

lined along the lower ground behind, but unable to break them. The French fell back down the slope to regroup, to attack again and again, perhaps ten times over the next hour and a half, before finally giving up on the stalemate. But at 7.30pm, the now critically stretched British position here was attacked once more – this time by Bonaparte’s Imperial Guard Foot Chasseurs and Grenadiers, his élite troops. Wellington kept his own thin lines, his own guardsmen, concealed until the last possible moment but then raked the advancing Frenchmen with musket and case shot. Many of the Imperial Guard battalions were torn apart, and the rest fell back towards La Belle Alliance. The Guard was defeated and Wellington signalled a general advance.

From the Lion Mound, however, you can still skirt the building site and take the access road, just before the bridge over the highway, which runs down to Hougoumont itself (25). This road takes you to the main north entrance that, in 1815, was secured by the solid wooden gate – focus of so many images of the fighting here. But the fighting was also intense and continuous around the courtyard and great barn, the chapel, the high surrounding walls and gardens, though the thick woodland south-east of the farm has now disappeared. It is estimated that 6,500 men of both sides died around Hougoumont.

Heading back towards the Lion Mound there is a lane which cuts diagonally across the valley towards La Belle Alliance and the area (29), where squares of the Imperial Guard made their last stand before beginning to retreat in good order towards Charleroi, providing a moving wall behind which the Emperor and the rest of the French army could fall back.

towards La Belle Alliance and the area (29), where squares of the Imperial Guard made their last stand before beginning to retreat in good order towards Charleroi, providing a moving wall behind which the Emperor and the rest of the French army could fall back.

From La Belle Alliance, the rue Du Champ de Bataille took us to the neighbouring village of Plancenoit (30) where, from late in the afternoon, other units of the Imperial Guard also tried to hold back the tide of Prussians attacking from the east. The old church has now been replaced  but this whole area was, once again, the scene of bitter hand-to-hand fighting for several hours until the battle was lost and the defenders also joined the general retreat. Plancenoit is certainly worth a visit though, with its original steep and cobbled main streets, its old farm and Prussian monument, so that it’s very easy to imagine the action that took place here in 1815.

but this whole area was, once again, the scene of bitter hand-to-hand fighting for several hours until the battle was lost and the defenders also joined the general retreat. Plancenoit is certainly worth a visit though, with its original steep and cobbled main streets, its old farm and Prussian monument, so that it’s very easy to imagine the action that took place here in 1815.

But we ended our own long day by picking up the car again and driving to the town of Waterloo (31) itself – actually a few kilometres north of Mont St. Jean – to visit the battlefield museum there, housed in the former coaching inn where Wellington stayed as his headquarters on the nights before and after the battle, thus providing the name by which English-speakers have subsequently always called the conflict: The Battle of Waterloo. The town of Waterloo seems to stretch forever along the N5 but it’s very lively and you’ll eventually come to a set of traffic lights with the domed Church of St. Joseph on the left (there’s also a memorial to the battle’s fallen British soldiers at the church) and the Wellington Museum on the right (if you’re heading in the direction of Brussels, of course). Another worthwhile visit and there’s good parking just behind the museum too.

Church of St. Joseph on the left (there’s also a memorial to the battle’s fallen British soldiers at the church) and the Wellington Museum on the right (if you’re heading in the direction of Brussels, of course). Another worthwhile visit and there’s good parking just behind the museum too.

Day Four

I’ve not included this section on the route maps but it’s worth mentioning that Brussels (an attractive city to visit in any case) has some interesting sites for those who wish to complete their Waterloo pilgrimage. The Grand-Place is the open square to which many of the Allied wounded were brought for whatever limited medical treatment was available to them, while the Hospital of the Augustine Sisters (rue de la Blanchisserie) has now replaced the building in which the Duchess of Richmond’s ball was held on the night before the battle. Wellington’s headquarters was located in the building still standing at 54-56 rue Royale.

This short guide is simply intended as a supplement to my Marianne Tambour novel, so I hope that readers will forgive details that may be missing due to its brevity. All the same, I also hope it might inspire those interested in the period to explore the area themselves. For those using public transport, the Rough Guide to Brussels (Martin Dunford and Phil Lee) gives good instructions. I’ve also been asked to say what the “highlights” of this trip may have been and, for me, the best bits were definitely (in no particular order) the Wellington Museum (31) in the town of Waterloo; the Lion Mound, Panorama and Visitor Centre (26) at the battlefield itself; the wonderful Napoleon Museum at Le Caillou (22); and the General Gérard Museum (10) at Ligny. Happy travelling!

David Ebsworth

Namur, September 2014

Leave a Reply