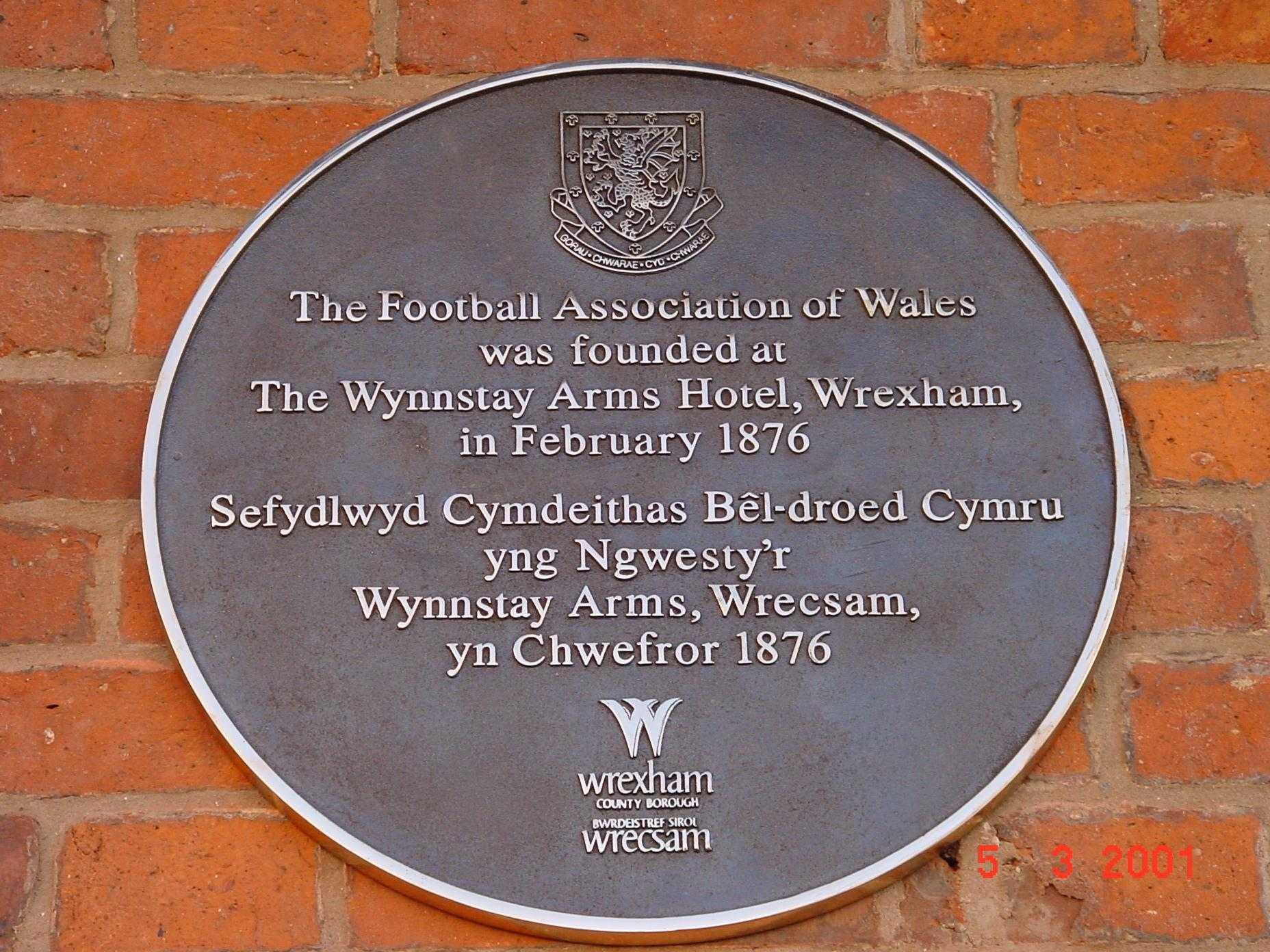

The year had an interesting beginning – the Football Association of Wales established at the town’s Wynnstay Hotel.

And then there were the visits by George Pinder’s Continental Circus and a memorable Horticultural Show, the first to be held in town for almost ten years. But in July 1876, Wrexham saw the most memorable event of the entire century – the Great Art Treasures Exhibition.

Sadly, there’s little left to remind us about how and where it all happened. But luckily we’ve still got the original catalogues for the Exhibition and, from this, as well as the newspaper reports of the day, we know the precise location and how it was all organised.

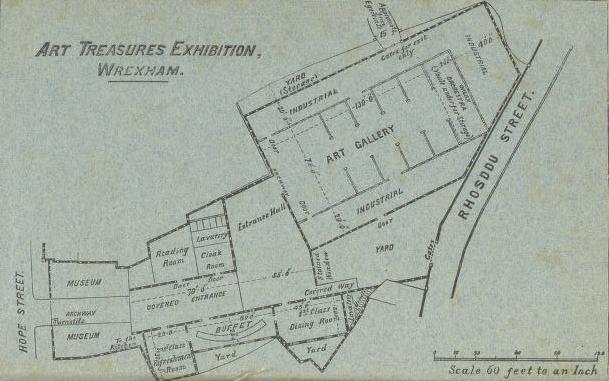

In Wrexham’s Hope Street, right across from the well-known and thatch-roofed Horse & Jockey pub stands the impressive Westminster Buildings at the centre of which stands an equally impressive archway – the Argyle Arch. The building itself had only recently been constructed by the Scottish engineer William Low, owner of the Vron Colliery and original architect for a tunnel under the English Channel. The building had been developed to provide a dowry for Low’s eldest daughter, Alison. But now the archway served as the entrance to the Exhibition. Turnstiles on Hope Street itself, gates and, just inside the arch, a museum on each side. Beyond the archway a zinc roof with skylights provided a covered passageway along what is now Argyle Street, with cloakrooms and dining facilities.

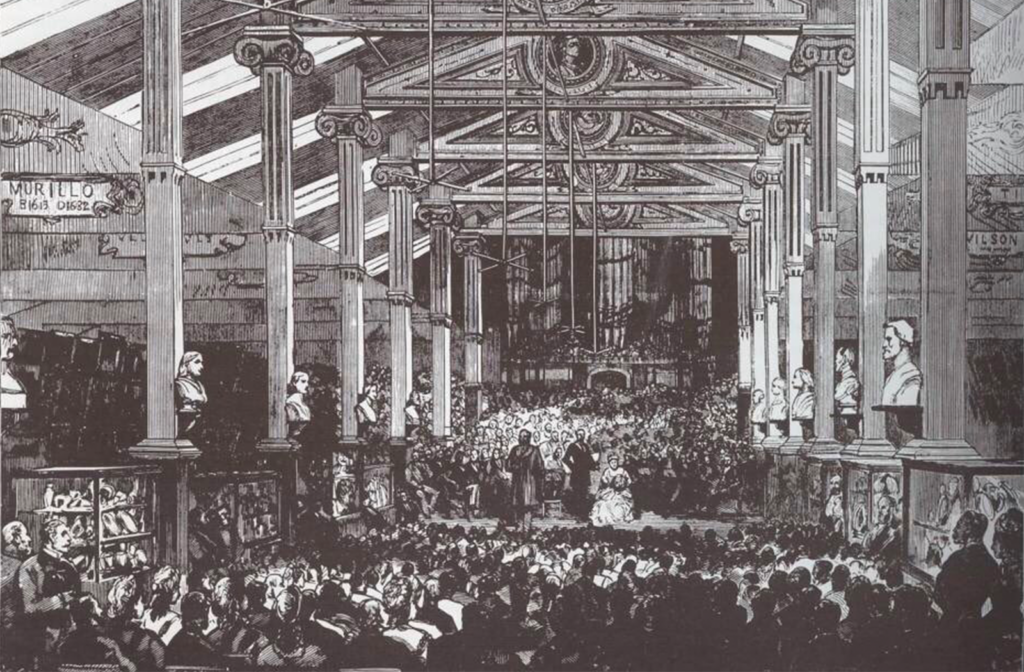

Past the buffets and restaurants, a large entrance hall graced with a fancy stained glass circular window. At the north-east corner of the hall, the double doorway into the Exhibition proper – an enormous pavilion, more zinc and glass, ornately carved wooden columns.

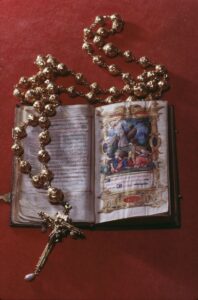

More than 1,000 paintings on display and antiquities galore, tens of thousands of items. The Exhibition opened in mid-July and would run for four months. Estimates of attendance vary between 50,000 and 80,000. Paintings by Joshua Reynolds, Murillo, Velasquez, Canaletto, Turner and countless others. Among the other works of art and antiquities, the rosary carried by Mary Queen of Scots to her execution…

…the watch which had once belonged to Charles the First…

…Becket’s grace cup…

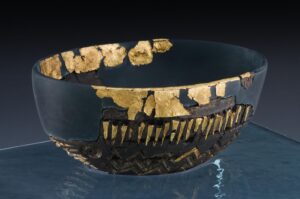

…the Caergwrle Bowl…

…and so much more.

Around the outside of the main art gallery, three additional annexes contained an impressive Industrial Exhibition. Here were displayed all the wonders of Wrexham’s many manufacturers and trades people. Steel and brick products, beers and ales, cartwheels, leather goods and textiles. Among the textiles, this wonder…

…the Wrexham Tailor’s Quilt – more properly, the Wrexham Tailor’s Coverlet. It had been patched together over ten years by local military master tailor, James Williams, from 4,525 separate pieces of cloth. And those fabulous images!

The key players responsible for bringing the Exhibition to Wrexham? Hugh Grosvenor, First Duke of Westminster. Denbighshire’s longstanding MP, Sir Watkin Williams Wynn. Denbighshire’s Lord Lieutenant, Major William Cornwallis West. Former Prime Minister, William Ewart Gladstone. Lord Penrhyn. Sir Robert Cunliffe. And, of course, William Low himself. But the man who served as the Exhibition’s General Manager – who pulled it all together – was William Chaffers, the great antiquarian.

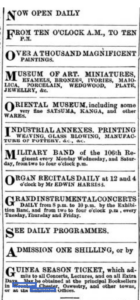

Yet the thing which made this all so extraordinary was the overall scope of the Exhibition. It opened at 10:00am every day and closed at 10:00pm each evening. Twelve hours per day. Seven days each week. For four months. And apart from all those art treasures, an almost continuous programme of lectures, musical performances, military bands, choirs and organ recitals.

All for a shilling. Or the one guinea season ticket.

Of course, the Exhibition had its critics as well. Here, a scathing report in The Spectator (28th October 1876).

This is how it begins…

“That art should se nicher in a region which we associate chiefly with coal and slate, is strange in the abstract, but especially surprising when one gets out of the train at Wrexham … and sees what an ugly and uninteresting place it is.”

And it doesn’t get any better as the article progresses over the following pages.

Apart from this, there were many questions about the Exhibition’s cost. The construction costs, for example. The original budget had been set at £2,500 but the actual cost came in at £3,942 16s 2d. Total expenditure for the Exhibition as a whole was £12,153 14s 11d, leaving the organisers with a deficit of £4,215 15s 9d (roughly the equivalent of £600,000 at today’s values).

But in all other respects, the Exhibition was a huge success for Wrexham. A commemorative medal was struck and awarded to all exhibitors and performers.

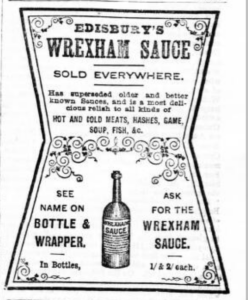

And it was a great boost to local commerce, with local entrepreneurs making the most of the opportunities provided by all those visitors to the town – men like the High Street pharmacist, J.F. Edisbury, who saw sales of his famous Wrexham Sauce rocket during the four months in question.

Of course, there were other momentous events in Wrexham that year – the first ever National Eisteddfod held in the town during August and, in November, its first tram system – but it’s the Art Treasures Exhibition which marks 1876 as the town “year of wonders”, its annus mirabilis.

Leave a Reply