The Kraals of Ulundi: A Novel of the Zulu War sparks some interesting issues…

- The 1964 Film Zulu and Apartheid

The film was directed by American screenwriter Cy Endfield and produced by Stanley Baker and Endfield, with Joseph E. Levine as executive producer. The screenplay is by John Prebble and Endfield, based on an article by Prebble, a historical writer. The film was produced by Stanley Baker’s

own company, Diamond Films. Shot mostly on location in South Africa (though not actually at Rorke’s Drift), Prebble and Endfield were formerly members of the Communist Party and Stanley Baker was a lifelong supporter of the Labour Party, a staunch Socialist. They had serious concerns about filming in a South Africa then in the grip of Apartheid, though it would have been absurd to make the movie anywhere else. But the South African Government applied strict conditions on the sixty British crew. Sexual relations with anybody of another race would result in imprisonment or flogging. Black actors were specifically prohibited from drinking in the onsite bar. And the extras were treated so badly by the authorities that Michael Caine promised never to make another film in South Africa until Apartheid fell – and never did. There is an urban myth that the Zulus had to be paid in cattle, to avoid Apartheid laws, but this isn’t true, and they were paid. Many of them were the grandchildren of men who fought in the battle, but that didn’t equip them for the role – so Baker arranged for them to be shown a B-movie US cavalry v. Indians western to help with their training.

- The Zulu Empire

The Zulus had become a powerful military state only in the first quarter of the Nineteenth Century under the leadership of King Shaka. Before Shaka, they were simply one of the many clans among the Ngoni people who had been part of the Bantu migrations down the east coast of Africa for over a thousand years. And this particular clan was established in the early 1700s by a man called Zulu, son of an Ngoni chieftain, Ntombela. The word iZulu literally means ‘sky’ or ‘heaven’, so that the clan name, AmaZulu, implied both that they were the People of the Man called Zulu, and also the People of Heaven. But Shaka had united the Zulus in a series of bloody civil wars, as well as being credited with the introduction, first, of the short stabbing spear, the iklwa – which we now know as the assegai – and, second, of the Zulu “bull-horn” fighting formation. In the decades that followed Shaka’s murder in 1828, the Zulus were frequently in conflict with the Dutch-Boer settlers around their borders, although relations with the British of neighbouring Natal and Cape Colony were excellent. The Zulus saw themselves as firm allies of Queen Victoria’s Empire and, by the 1870s, the Zulu economy was thriving – a cattle-based economy in which the standing army of age-related regiments played a crucial role.

- The Causes of War

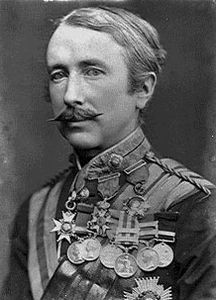

In the late 1870s, the British in southern Africa’s Cape Colony – principally under the auspices of

High Commissioner Sir Henry Bartle-Frere – were involved in a land-grab. Using the pretext of skirmishes between the settlers and local tribes, they had already annexed the Dutch-Boer Republic of the Transvaal (1877), and then fought a disastrous war against the Pedi tribe of Sekukhuniland in 1878. Undeterred, and still hoping to snatch more territory as part of a consolidated British South Africa, Bartle-Frere cast greedy eyes on the independent Kingdom of Zululand. He was largely responsible for starting a series of rumours to frighten the white population of Natal Province into believing an invasion by the neighbouring Zulus to be imminent. And when the anxiety of the 800 European citizens of Natal had risen to fever-pitch, he sent an ultimatum to the Zulu King, Cetshwayo – an ultimatum with which, he knew, Cetshwayo could never comply. A demand to disband the Zulu army. A demand to hand over the sons of an important Zulu chieftain for trial and punishment in British Natal for minor cross-border infringements. A demand for huge amounts of reparation arising from those same infringements. As Bartle-Frere knew would be the case, a bemused Cetshwayo ignored the ultimatum and, in January 1879, four columns of well-trained British troops invaded Zululand under the command of Lord Chelmsford. Chelmsford’s own Centre Column crossed the border just below the mission station at Rorke’s Drift and most of his 4,700 men advanced to the mountain called Isandlwana. On the morning of 22nd January, Chelmsford divided his force, leaving around 1,800 men to protect their camp and was lured east with the rest in pursuit of the main Zulu army. The Zulu army, meanwhile, had actually moved to surround the camp. The attack that followed annihilated, almost to a man, the British force, despite being equipped with the most modern rifles and facing a foe armed with little more than spears and shields. The disaster was only mitigated when, later that same day, 4,000 of the Zulus attacked the tiny British garrison at Rorke’s Drift itself and, miraculously, the defenders held the mission station until the following morning, when a relief column appeared.

- The Witts and White Settlers in Zululand

The first European settlers started to arrive in Zululand around 1824, by ship from the Cape, and established Port Natal, later re-named Durban. The stories of some of them, like Henry Frances Fynn and Lieutenant Farewell, are famous. And, of course, it did not take long before Christianity followed them. From the mid-1850s, the Zulus allowed Norwegian Lutheran and British Anglican mission stations and, in 1869, also Germans from the Hermannsburg Missionary Society. When Cetshwayo became king, he continued to permit European missionaries in Zululand, though their activities were sometimes less than welcome. He did not harm or persecute the missionaries themselves, but several converts were killed. The missionaries, for their part, were a source of hostile reports, particularly when their attempts to gain converts were unsuccessful. But by the end of 1878, most missionaries had left Zululand, either persuaded by the rumour of possible Zulu aggression, or sometimes its author. One of the few exceptions was the outpost run by the Church of Sweden Mission, and only recently established by the Reverend Otto Witt, at a remote place called Rorke’s Drift – which he named Oscarberg, after the King of Sweden. When the British army arrived there, to begin the invasion, Witt’s tiny church was requisitioned and he sent his wife and young daughter (she was actually only a couple of years old at the time) away to Msinga. Witt himself left the mission station on the morning of the battle, long before it started, and the film’s characterization of him is only slightly less shameful and distorted than that of poor Henry Hook!

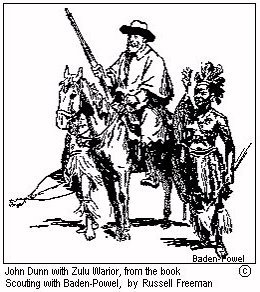

But the missionaries weren’t the only Europeans heavily involved in Zululand’s internal politics.

From the 1850s, white hunters and traders regularly operated in Zulu territory and much of the trade involved the sale of firearms. One of the most famous was John Robert Dunn. He had once fought alongside a rival of Cetshwayo’s but finally became one of the king’s chief advisors. In this position of power, Dunn accrued considerable lands, wealth and dozens of Zulu wives. Yet, with the invasion in 1879, he deserted Cetshwayo and went over to the British. In the aftermath of the war, Zululand was broken up into thirteen sub-kingdoms, and Dunn was rewarded by being given the largest of those, the region closest to Durban. King John Dunn – King Jantoni – ruled there until 1883 when, following Cetshwayo’s restoration, his lands were given the status of a Reserve Territory and Dunn himself was given the title of regional chief. He died in August 1895 at Emoyeni and, by that time, had 48 Zulu wives and 117 children. Twenty-three of his wives and seventy-nine of his children survived him. It was reported in 2004 that his descendants, the extended Dunn family, then numbered 6,000, scattered across every continent. They had just won a court case giving them permanent rights to some of the land granted to Dunn in 1879. One of his great-grandsons, Daniel Dunn, runs an independent tour company in South Africa, and is Chairman of the Dunn Descendants’ Association.

- Chard and Bromhead

Lieutenants John Rouse Merriott Chard and Gonville “Gunny” Bromhead were unlikely heroes. Chard was 31, a competent officer of engineers but described by his senior officer as ‘hopelessly slow and slack.’ Bromhead was two years older and seen action on the Cape Frontier but he suffered from impaired hearing. And neither of them looked even remotely like Stanley Baker or Michael Caine! But was it Chard and Bromhead who saved the day? An interesting account by Henry Hook (supported by other testimony) confirms that, when news of Isandlwana arrived, with the sure knowledge that

a Zulu attack on Rorke’s Drift was imminent, Chard and Bromhead initially gave orders for the place to be abandoned. According to Hook’s account, it was Sub-Assistant Commissary James Langley Dalton who persuaded them that flight would be suicidal, explained how the post could best be defended, and pointed to the work already undertaken to fortify the perimeter, with sacks of corn and biscuit boxes, and the London Gazette certainly gave him credit for superintending the work of the defence. A shame, therefore, that Dalton did not receive his Victoria Cross until six months after the other recipients.

- Cetshwayo the King

In 1879, King Cetshwayo kaMpande was 53 years old. He was a huge man, who had killed his own brother in battle during 1856 but did not ascend the throne until 1873, after the death of his father. In fact, it was Britain’s Director of Native Policy in Natal, Sir Theophilus Shepstone, who crowned him, though it was done as a shoddy piece of theatrical drama. All the same, the coronation did much to cement Cetshwayo’s belief that he was an ally of Britain. As a result, he was shocked by the British invasion and tried to avoid open warfare, with his army commanders usually acting in defiance of his orders when they attacked at Isandlwana and elsewhere. Throughout the six months of the war, he continuously sent peace envoys to Lord Chelmsford. But after the final defeat at Ulundi, he was captured and sent into exile at Cape Town. In the film, Zulu, the role of King Cetshwayo was played by his direct descendant, Prince Mangosuthu Buthelezi. The wedding dance was choreographed by Buthelezi’s mother, a tribal historian, and supervised by stuntman Simon Sabela, who later became South Africa’s first black film director.

- Disaster after disaster – six more months and the end of a dynasty

The battles at Isandlwana and Rorke’s Drift took place during the opening weeks of the war – but the conflict dragged on for another six months. And Isandlwana wasn’t the only disaster. On 12th March 1879, most of Captain David Moriarty’s command (104 men) was destroyed at the Intombe Drift. On 28th March, 250 men of Sir Evelyn Wood’s command were killed during the defeat at Hlobane Mountain. Meanwhile, 137 men died during the 10-week siege of the Eshowe garrison by the Zulus. There were successes too, of course. At Khambula, for example, on 29th March and in the final battle, at Ulundi, on 4th July. But, before that, on 1st June 1879, the French Prince Imperial, Louis Napoleon,

had taken part in a patrol, been ambushed by Zulus, and killed. Louis was Napoleon Bonaparte’s great-nephew and heir to the French throne. At the time, however, his family was exiled in Britain and Louis had begged leave to accompany the British forces in Zululand. He was permitted to do so, by Queen Victoria, on the strict understanding that he should be kept safe. Britain suffered a huge stigma with Louis Napoleon’s death and the war had the unexpected consequence of bringing the French Imperial dynasty to an end.

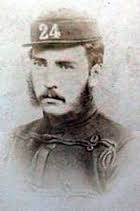

- The Welsh at Rorke’s Drift

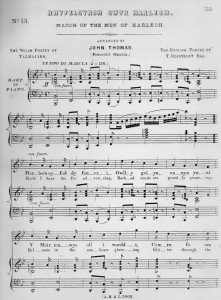

The film Zulu portrays the 24th Regiment as a “Welsh” unit though, in 1879, it was still known as the 2nd Warwickshire Regiment and was only re-designated as the South Wales Borderers in 1881. And in 1969, it became part of the Royal Regiment of Wales. It’s certainly true that the depot for the 24th was in  Brecon, but the Welsh contingent at Rorke’s Drift was no more than about 15%. And the regimental song was still The Warwickshire Lads. So nobody sang Men of Harlech. Not then. But in 1999, the 120th anniversary of the battle, the Choir of the Royal Welsh were invited back to Rorke’s Drift to take part in a memorial service. And that service concluded with the Choir singing Men of Harlech. All very emotional. The anniversary was important too, due to the participation of 3,000 Zulus, in commemorations at both Isandlwana and Rorke’s Drift – and the unveiling of the first-ever memorials to the Zulus themselves, who had died in the defence of their homeland.

Brecon, but the Welsh contingent at Rorke’s Drift was no more than about 15%. And the regimental song was still The Warwickshire Lads. So nobody sang Men of Harlech. Not then. But in 1999, the 120th anniversary of the battle, the Choir of the Royal Welsh were invited back to Rorke’s Drift to take part in a memorial service. And that service concluded with the Choir singing Men of Harlech. All very emotional. The anniversary was important too, due to the participation of 3,000 Zulus, in commemorations at both Isandlwana and Rorke’s Drift – and the unveiling of the first-ever memorials to the Zulus themselves, who had died in the defence of their homeland.

- Victoria Crosses and the fate of heroes

Eleven men received Victoria Crosses in the aftermath of Rorke’s Drift. A twelfth was awarded, to Sergeant Bourne, but he turned it down in favour of a Commission. He eventually reached the rank of Lieutenant-Colonel and only died in 1945. Of the others… John Chard went on to fight at Ulundi, and was later promoted to major but died from cancer of the tongue in 1897; Surgeon James Henry Reynolds (and his fox terrier, Dick, included in the commendation)

was promoted to Lieutenant-Colonel, and died in 1932; Henry Hook, much maligned by the film, Zulu, died of tuberculosis in 1905; Frederick Hitch, died in 1913; Gonville Bromhead was later promoted to major but died of typhoid in India, in 1891; Robert Jones shot himself in 1898, driven mad with nightmares ever since the battle; William Allen later made sergeant but died of influenza in 1890; William Jones became unemployed when he left the army, later spent some time with Buffalo Bill’s Wild West Show, but died in the workhouse, in 1913, and was buried in a pauper’s grave; John

Fielding (enlisted as Williams) died in Cwmbran in 1932; James Dalton, Assistant Commissary, now credited with designing the defence, died at the age of 54 in 1887; and Corporal Ferdinand Schiess also became unemployed and homeless. The Royal Navy found him on the streets of Durban and offered him passage to England, but he died on the voyage.

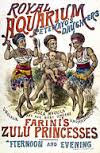

Chard and Bromhead received a certain celebrity status but, as we know,  did not live long to enjoy it. The Zulus also achieved celebrity too. There had been Zulu performances on London stages since the 1850s but, in the aftermath of Isandlwana, that enterprising showman, the Great Farini (William Leonard Hunt), began to bring troupes of Zulus to Britain to appear in large-scale shows at places like the Royal Aquarium and other theatres. They were received to great acclaim, for Britain’s invasion of Zululand had not been popular. News of its outbreak had been greeted with hostility among the public and in the press, and the respect which had grown up between British soldiers and Zulu warriors on the battlefields had somehow spilled over into the psyche of their respective communities – and remains there to this day.

did not live long to enjoy it. The Zulus also achieved celebrity too. There had been Zulu performances on London stages since the 1850s but, in the aftermath of Isandlwana, that enterprising showman, the Great Farini (William Leonard Hunt), began to bring troupes of Zulus to Britain to appear in large-scale shows at places like the Royal Aquarium and other theatres. They were received to great acclaim, for Britain’s invasion of Zululand had not been popular. News of its outbreak had been greeted with hostility among the public and in the press, and the respect which had grown up between British soldiers and Zulu warriors on the battlefields had somehow spilled over into the psyche of their respective communities – and remains there to this day.

- The Aftermath

Lord Chelmsford had been sent home after his final defeat of the Zulus at Ulundi on 4th July 1879. He was replaced by Sir Garnet Wolseley, who had wanted the glory of that victory himself, and therefore looked around for other options. As part of Sir Henry Bartle-Frere’s original land-grab plan, the British had invaded the Pedi kingdom of Sekukhuniland and suffered in a disastrous little war. Wolseley decided to settle the score, issued yet another impossible ultimatum and then launched an invasion, which gave him an ignominious victory at the Battle of Tsate. Meanwhile, friction between the various sub-kingdoms into which Britain had divided the Zulu nation erupted into a vicious civil war. Cetshwayo was released and, in a belated attempt to regain stability, the British restored him to the throne. Yet Cetshwayo was wounded in a second battle of Ulundi – this time fighting his own people. He fled and died in February 1884. The cause of death is still disputed. And the weakening of both the Pedi and the Zulus served only to strengthen the Dutch-Boers who, in 1880, finally rebelled against the annexation of the Transvaal. The first Anglo-Boer War – the Boer War of Independence – broke out and ended a year later with a crushing British defeat at Majuba Hill and the Transvaal regaining its independence. But British ambitions still intensified with the discovery of gold and a second Anglo-Boer War took place in

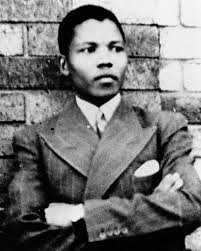

1899-1902, resulting in a British “victory” (owing a great deal to the use of internment camps in which 27,000 Boer women and children died of malnutrition and disease) and the Boers forced to acknowledge British sovereignty. But British attempts to anglicise the region were failing, and the Boer Afrikaners gaining ever more power. In 1909, the Union of South Africa was established, technically still British territory but with home rule for the Afrikaners. Within four years, legislation was being introduced which would

lay the foundations for the eventual system that we now know as Apartheid that endured until the 1990s, bringing almost a century of segregation and humiliation to the Zulu people as well as all other Black and Asian South Africans. South Africa became fully sovereign in 1931.

Extremely interesting and informative. An excellent unbiased account.

Hi Brian. Huge apology but I hadn’t spotted your comment. All the same, glad you liked the post.