The Kraals of Ulundi and the Nelson Mandela Link

In November 2013, I was able to make the trip to KwaZulu-Natal in South Africa to check out the locations for book number three, The Kraals of Ulundi: a Novel of the Zulu War.

Then, just a few days after our return to the UK, came the news of Nelson Mandela’s death – and several people e-mailed me to ask whether there was a direct link between this desperately sad event and the story of the Zulu people that I’ve set down in Kraals. And the subject has come up over and over again in the presentations I’ve made snce the novel’s release.

Well, of course there’s a link. And not only for the Zulus but for all the other citizens of South Africa too, including the Xhosa people – closely related to the Zulus – to whom Nelson Mandela belongs.

In the Historical Notes for Kraals, I found it necessary to explain some of this – at least in summary. The Zulus were eventually defeated by the British army in 1879, during an inexcusable land grab by the British Empire. The Zulu king, Cetshwayo, was sent into exile and imprisonment, to Cape Town and within sight of Robben Island. The island had been a place of incarceration for many years already – both as a leper colony and as a prison. Cetshwayo had a terror of being sent there although he was actually detained in Cape Town itself (Nelson Mandela would later spend 18 of his 27 years’ incarceration on Robben Island). But within three years friction between the various sub-kingdoms into which Britain had divided the Zulu nation erupted into a vicious civil war. Cetshwayo was released, in a belated attempt to regain stability, the British restored him to the throne. Yet Cetshwayo was wounded in a second battle of Ulundi – this time fighting his own people. He fled and died in February 1884. The cause of death is still disputed.

summary. The Zulus were eventually defeated by the British army in 1879, during an inexcusable land grab by the British Empire. The Zulu king, Cetshwayo, was sent into exile and imprisonment, to Cape Town and within sight of Robben Island. The island had been a place of incarceration for many years already – both as a leper colony and as a prison. Cetshwayo had a terror of being sent there although he was actually detained in Cape Town itself (Nelson Mandela would later spend 18 of his 27 years’ incarceration on Robben Island). But within three years friction between the various sub-kingdoms into which Britain had divided the Zulu nation erupted into a vicious civil war. Cetshwayo was released, in a belated attempt to regain stability, the British restored him to the throne. Yet Cetshwayo was wounded in a second battle of Ulundi – this time fighting his own people. He fled and died in February 1884. The cause of death is still disputed.

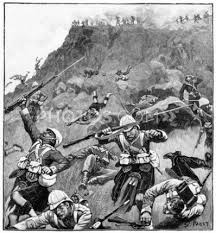

Cetshwayo’s 15-year old son, Dinizulu, was later declared his successor with the help of the Boers in return for a promise of land. This did not please the British who had ambitions to bring together all the states of southern Africa into a single dominion. Not only the Zulus stood in the  way of this ambition but also the Boers. The British had forcibly annexed the independent Boer Republic of the Transvaal in 1877 and, when the Boers rebelled against this in 1880, the first Anglo-Boer War – the Boer War of Independence – broke out and ended a year later with a crushing British defeat at Majuba Hill and the Transvaal regaining its independence. The Boers’ acquisition of so much new territory from the Zulus was seen by the British as a serious threat, and they annexed the whole of Zululand in 1887. British ambitions intensified with the discovery of gold and a second Anglo-Boer War took place in 1899-1902, resulting in a British “victory” (owing a great deal to the use of internment camps in which 27,000 Boer women and children died of malnutrition and disease) and the Boers forced to acknowledge British sovereignty. But British attempts to anglicise the region were failing, and the Boer Afrikaners gaining ever more power. At the same time, indigenous folk and immigrant Asian labour were becoming increasingly marginalised, although still badly divided into separate factions. In 1906, 4,000 Zulus were killed in the Bambatha Uprising after rebelling against repressive taxes. As a result, the British imprisoned Dinizulu on the island of St Helena – where Napoleon, of course, had died.

way of this ambition but also the Boers. The British had forcibly annexed the independent Boer Republic of the Transvaal in 1877 and, when the Boers rebelled against this in 1880, the first Anglo-Boer War – the Boer War of Independence – broke out and ended a year later with a crushing British defeat at Majuba Hill and the Transvaal regaining its independence. The Boers’ acquisition of so much new territory from the Zulus was seen by the British as a serious threat, and they annexed the whole of Zululand in 1887. British ambitions intensified with the discovery of gold and a second Anglo-Boer War took place in 1899-1902, resulting in a British “victory” (owing a great deal to the use of internment camps in which 27,000 Boer women and children died of malnutrition and disease) and the Boers forced to acknowledge British sovereignty. But British attempts to anglicise the region were failing, and the Boer Afrikaners gaining ever more power. At the same time, indigenous folk and immigrant Asian labour were becoming increasingly marginalised, although still badly divided into separate factions. In 1906, 4,000 Zulus were killed in the Bambatha Uprising after rebelling against repressive taxes. As a result, the British imprisoned Dinizulu on the island of St Helena – where Napoleon, of course, had died.

In 1909, the Union of South Africa was established, technically still British territory but with home rule for the Afrikaners. Within four years, legislation was being introduced which would lay the foundations for the eventual system that we now know as apartheid that endured until the 1990s, bringing almost a century of segregation and humiliation to the Zulu people as well as all other Black and Asian South Africans – themselves fatally weakened through the divisions imposed by the British in 1879. The line of Zulu kings continued, although subsequent descendants of Cetshwayo were denied any real power by the South African government.

lay the foundations for the eventual system that we now know as apartheid that endured until the 1990s, bringing almost a century of segregation and humiliation to the Zulu people as well as all other Black and Asian South Africans – themselves fatally weakened through the divisions imposed by the British in 1879. The line of Zulu kings continued, although subsequent descendants of Cetshwayo were denied any real power by the South African government.

In 1977 a Legislative Assembly of KwaZulu was constituted, yet the actual status of the region continued to be disputed even after the ANC victory and election of Nelson Mandela in 1994. But at that point, KwaZulu was merged with the former Natal and the current region, KwaZulu-Natal established. It remains a very distinct province within the modern South Africa and with its own legislature. There is also a reigning Zulu king – King Goodwill Zwelithini kaBhekuzulu – though without any direct political power, yet still exerting considerable influence.

So the roots of much recent history in South Africa, much of the tragedy, much of the division, are buried in that decision by British High Commissioner, Sir Henry Bartle Frere, to launch his illicit invasion of Zululand in January 1879. And, for me, the reconciliation and forgiveness that Mandela advocated so strongly is all the more remarkable because it must cope not only with the travesties of apartheid but, in practice, with all those accumulated over the years since 1879.

So the roots of much recent history in South Africa, much of the tragedy, much of the division, are buried in that decision by British High Commissioner, Sir Henry Bartle Frere, to launch his illicit invasion of Zululand in January 1879. And, for me, the reconciliation and forgiveness that Mandela advocated so strongly is all the more remarkable because it must cope not only with the travesties of apartheid but, in practice, with all those accumulated over the years since 1879.

Rest in peace, Tata Madiba! (Nelson Rolihlahla Mandela, July 1918 – December 2013).

Nelson Mandela was truly a great man.

To face racial prejudice, injustice, being denied a voice in his own country and yet have the intelligence and forgiveness to lead a nation where all, no matter their colour should be treated equally and any form of revenge would of destroyed the country he loved so much.

And of course the British wernt the only Europeans in Africa. The French, Dutch, Portuguese and Italians among others all shaped African history with their colonisation for good and for bad.

Thanks Michael. Nice comment and quite correct about other European nations’ involvement in Africa, of course!