In November 2013, we travel the 5,900 miles from London to Durban to visit the South African province of KwaZulu-Natal – which covers the former Kingdom of the Zulus, the British colony of Natal, and part of the Dutch-Boer Republic of the Transvaal. The province’s population is 10.26 million (20% of South Africa’s total) and the main languages are isiZulu (78%), followed by English and Afrikaans. 87% of the folk here are Black African (almost exclusively Zulu); 9% are Indian/Asian; and 4% are White. We’ve come here to see the province itself – its people, its scenery, its wildlife – but also to check out locations from the third book, The Kraals of Ulundi: A Novel of the Zulu War. So off we go, fully equipped with our Malarone tablets and a very nice, borrowed Lumix camera.

King Shaka airport in Durban is an easy place where we freshen up after the 12-hour, mostly sleepless overnight from Heathrow, with us both still unsure about whether we should have come. Ann has lost her brother Robert (64) only the day before we left. We had basically decided to cancel until the family – close-knit and self-supporting as usual – insisted that we should proceed. So here we are, collecting a Toyota Corolla from the Avis desk, then driving north and west on the A3 until we take a slight detour, following the R103 on the route taken by British troops marching from Durban itself to replace those killed at Isandlwana and to supplement Chelmsford’s army for the second invasion of Zululand in 1879. We drive to viewpoints from which we can see the fabulous Valley of a Thousand Hills, mostly flat-topped and misted, away to the north.

On a Sunday afternoon in Pietermaritzburg, it’s hard not to feel out of place. The guide book has promised that a wander along Church Street in the heart of KwaZulu Natal’s capital city – tiny compared to its sprawling coastal neighbour, Durban – will reveal some wonders of colonial architecture (St Peter’s Church; the 1914-18 and 1939-45 War Memorial Arch; the monument to white members of the Natal Native Contingent killed at Isandlwana; the Voortrekker Museum; the Old City Hall; the Art Gallery; and the statue of Gandhi who, as a solicitor in the late 1880s, was thrown off a train here because he was “coloured”). But the guide book does not warn me that I will now see only African faces here, and few of them looking in any way prosperous. The mannequins in the clothes store windows are all white, the shoppers inside all Black. There are littered remains of the morning’s mufti market, and crowds still listening to the Zulu singers and dancers on a street corner. This is a city built by one culture, now occupied by another. The modern Capital Building speaks of new beginnings but it all feels too early to tell what they might be. Perhaps this place will look different on, say, a busy Thursday morning. And we are very tired, when all’s said and done!

Granny Mouse’s Country House at Howick is a distinctive collection of whitewashed thatch cottages with a river at its back, Oribi bush buck jumping on the hills beyond, then watchful and

pensive as a wild cat stalks harmlessly past. It smells of soft herbs along garden walks and the Xhosa or Zulu staff are attentive but without any sense of false servility. They feed us fish cake starters, then cheese-stuffed chicken and mutton curry with sambals, all for 300 Rand (£20). The birdlife is phenomenal too – Fork-Tailed Drongos and Widow-Birds abound!

Day Two finds us back on the R103, still following the route of those Zulu War drafts through Balgowan and Mooi River to Griffin’s Hill – where I’d set one of the chapters in The Kraals of Ulundi. Here too we see our first “township”, Mimosaville, hundreds of small settlements, each consisting of two or three square or round huts, some with thatch, others with corrugated iron. There are few vehicles, since people walk prodigious distances here, or cluster at the roadside waiting for one of the white crew vans and the yellow stripe that denotes them as local buses. Not far beyond is another of the book’s locations, Fort Durnford, on the banks of the Bushman’s River at Estcourt and built by Colonel Anthony Durnford, who was later to receive (unjustly) much of the blame for the Isandlwana disaster. Further again, we stop beside the railway tracks to look at a monument commemorating the capture of war correspondent Winston Churchil by the Boers in 1899. Then it’s on to Winterton on the R74 for lunch (cold beer and mussels).

Day Two finds us back on the R103, still following the route of those Zulu War drafts through Balgowan and Mooi River to Griffin’s Hill – where I’d set one of the chapters in The Kraals of Ulundi. Here too we see our first “township”, Mimosaville, hundreds of small settlements, each consisting of two or three square or round huts, some with thatch, others with corrugated iron. There are few vehicles, since people walk prodigious distances here, or cluster at the roadside waiting for one of the white crew vans and the yellow stripe that denotes them as local buses. Not far beyond is another of the book’s locations, Fort Durnford, on the banks of the Bushman’s River at Estcourt and built by Colonel Anthony Durnford, who was later to receive (unjustly) much of the blame for the Isandlwana disaster. Further again, we stop beside the railway tracks to look at a monument commemorating the capture of war correspondent Winston Churchil by the Boers in 1899. Then it’s on to Winterton on the R74 for lunch (cold beer and mussels).

The road that winds upwards from Winterton to Cathedral Peak is full of new images. Lush valleys with homesteads dotted along them, many dug into the deeply red clay of the hillsides. There are the ubiquitous herds of Ngoni cattle, or goats, with their minders. And always ahead are the dragon’s teeth peaks of the Drakensbergs. The Cathedral Peak Hotel is one of those places where it’s forbidden to carry your own luggage and gentlemen are not allowed to wear shorts in the restaurant after 8.00pm. Lovely room though, with tea served on the terrace at 4.00 in the afternoon. The scenery is fabulous too, high up here in the Drakensberg Mountains, encouraging us to complete a two-hour early evening climb up one of the valleys to find the Doreen Falls and do a spot of bird-watching. Wonderful variety here, from the Hadeda Ibis to the Common Scimitarbill. Then back for shower and impressive buffet dinner – roast pork for Ann and Lamb Navarin for me.

Moses Mahuli is the first Zulu that we have a chance to meet in any depth. He turns up at the hotel to guide a small group of us (six in total) up the

mountain tracks towards the Cathedral, the Bell and other peaks that dominate the landscape here, so that we can visit a small cave decorated with prehistoric paintings by the San bushmen. Strangely, the rest of our party are all from the Chester area, and one of them – Sarah Andrew – involved in the Chester Literary Festival. We chat about books and press Moses for information about… his family; the supply of water to local settlements (all directly from mountain springs); about some basic isiZulu phrases; and, of course, the nature of the paintings. These were executed in blood by the bushmen’s iSangoma and iNyanga witch doctors. They depict eland, bush buck, matchstick men hunters, and the shamans themselves. In the afternoon, we lounge by the pool, soaking up sun and gazing at the Baboon Rock, high on the opposite ridge.

A ferociously hot wind scours the summit of Spioeonkop. It’s Wednesday morning and we’ve followed the long dirt track from the main road between Bergville and Ladysmith to get up here. This is the site of a battle (23-24 January 1900) in the Second Boer War and resulted in 1700 casualties for the British, 200 for the Boers. 243 British soldiers are buried here and the lines of their shallow trenches are well-marked. In a strange twist of fate, the British commander decided during the final night that his position was untenable and withdrew, not knowing that the Boers had already done the same. The Boers returned when they discovered the British had gone, of course. But it’s a spectacular spot, with the wide uThukela River flowing below us and the whole of Zululand spread out in the distance. The battle became synonymous with desperate struggle and gave its name, of course, to the terrace at Liverpool Football Club’s ground that we still call ‘The Kop’. A few miles further north is the scene of another such struggle, the 118-day siege of Ladysmith at the end of 1899 when the local inhabitants and British garrison were subjected to constant bombardment by Boer artillery until they were finally relieved by General Redvers Buller. This lively and cosmopolitan town has recently renewed its fame through the success of the Ladysmith Black Mambazo. Diamonds on the soles of their shoes!

Since we needed somewhere to break our journey on this long day, I had looked up places to have lunch in Dundee – not too far from Ladysmith. And I had come across a lady called Elisabeth Durham, owner of the Chez Nous Guest House. It turned out that she’s one of the world’s leading experts on the French Prince Imperial, Louis Napoleon, who died in Zululand in 1879. So she treats us to a splendid meal and we swap stories all afternoon. A real gem!

In the middle of the afternoon on Wednesday 22nd January 1879, Captain Reginald Younghusband, 2nd Battalion, 24th Foot, stood on a rocky shoulder of the sphinx-shaped mountain of Isandlwana with the few survivors of his ‘C’ Company. The Zulus swarming up the rocks towards him stopped as they realised he was performing a ritual ceremony of some sort, for he was picking his way through the boulders to shake hands with each of his men. Then he turned, took a last look at the carnage below, where the 1,357 men of his own regiment, the Natal Mounted Police, the Natal Native Contingent and others had been annihilated by the superior generalship and numbers of a 25,000-strong Zulu army that British commanders had seriously underestimated. According to Zulu accounts, at that moment an eclipse blotted out the sun, Younghusband drew his sword, waved it above his head, and then led his companions in a suicidal final charge down the hill. The spot where they died is marked by a cairn of white stones that also looks out over the lonely markers – each covering a spot where groups of soldiers fell and were buried (but only four months later) dotted widely across the landscape from here to the donga where Major Anthony Durnford (we came across him at Fort Durnford on Monday) began a stubborn rearguard action with his mounted infantry earlier in the battle. Along a path there is also an exquisite Zulu memorial to those who died here, fighting to defend their land from an illegal invasion. It is a highly symbolic monument containing much Zulu imagery but, for the Zulus themselves, it is less symbolic than the simple thorn bush that stands beside it, planted to ward off evil and to pacify the shades of the Zulu dead. Our guide here is Alistair Lamont and he explains this story – a familiar one for me – in a way that is fresh and emotionally charged, before delivering us safely back to the superlative Fugitives’ Drift Lodge where we arrived last night (Wednesday), to be greeted by a herd of giraffes.

Fugitives’ Drift itself is aptly named – in honour of those very few men who escaped here after the slaughter of Isandlwana. The drift itself is a crossing place in the river, a couple of miles from

the battlefield, and running through a rocky ravine. Most of those who got this far were killed anyway, speared or shot as they tried to swim the wide and fast-flowing stream by Zulus on the northern bank. And even those who reached the southern bank weren’t safe. On Thursday afternoon, our 19-year old guide, Adam, leads us through the paths, with giraffe and impala all around, to find the site where two of the day’s posthumous Victoria Cross recipients – Lieutenants Melville and Coghill – are buried. A sad place, since Melville had carried Coghill half a mile from the river below, up the most impossible slope, only to be caught and killed at the very moment when they seemed to have escaped. They are strongly commemorated at the Lodge, established in the 1970s by the Rattray family and used as a base not only for holidays but also for the David Rattray Foundation which uses charitable donations in conjunction with the local communities and co-operatives to fund a batch of schools, housing projects and community business initiatives. Sadly, David himself (a renowned historian) was murdered here during an armed robbery in 2007.

The old Zulu lady who looks after the monument to French Prince Imperial Louis Napoleon seems to have a sickle embedded in the top of her head. It turns out that simply keeps it there when it’s not in use.

‘Sawubona, mama,’ I say to her. I see you.

‘Yebo, sawubona,’ she beams. That’s good. She sees me also.

We sign the battered visitor book that can’t have been checked for twenty years and in this most lonely part of Zululand, many kilometres from Nqutu, we commune with the spirit of the man who’s featured so much in my writing for the past year. Then the eight grandchildren all turn up and I decide to ask the oldest, maybe Hannah’s age, what happened here?

‘Ah,’ she says. ‘It was 1994, and Napoleon came here with the Apartheid Man to count our hills. So the Zulus stabbed him.’ She makes an impressive stabbing gesture to underline the ending.

Well, it’s as good a story as mine, I have to admit!

The defenders of Rorke’s Drift, contrary to the Michael Caine film, Zulu, did not sing Men of Harlech when the 100-strong garrison was attacked by 4,000 Zulus in the aftermath of Isandlwana.

But more than a century later, on 22nd January 1999, it was sung by 120 men of the Royal Welsh Regiment who came here to attend a memorial service in the small church that now stands on the site of the former storehouse. Unknown to them, and outside the church, three thousand members of today’s Zulu population were gathering on the car park outside. Most had walked – as Zulus often do – from as far as ten miles away. And, as the last Welsh voices fell silent, they began to hear the strains of the beautiful isiZulu, singing that echoed against the Oskarberg Mountain, Shiyane, chanting verses in praise of their former enemies, still remembered here, in a ceremony of reconciliation. Alistair Lamont tells the story of the defence in a moving way, with greater drama than even the film could achieve. More Victoria Crosses won here than in any other single battle, eleven in total, and the honour of the Empire at least partially restored after the shame of Isandlwana. Yet many of the recipients ended their days as paupers or worse, cast aside both by the authorities and also the society that sent them here in the first place, to fight yet another unjustified war. For Queen and Country, I suppose. But why, exactly? And for whose benefit?

This is a real land of contrasts. The dirt roads and homesteads between the various sites around Fugitives’ Drift suddenly give way to tarmac and shopping malls in towns like Nqutu. Religion is a funny old thing here too. Lots of Gospel-style faith and also the very popular Church of Bethlehem – which, to their credit, at least doesn’t rely on material wealth. And mixed with these are the traditional beliefs, each settlement still having its iSangoma, iNyanga and iSanusi.

The Isandlwana story comes to an end – at least partially – on a neglected piece of ground just outside the modern town of Ulundi. We have arrived here by way of the EmaKhosini Valley – the Zulus’ Valley of the Kings – where seven of their original pre-Shaka rulers are buried, and the Spirit of Emakhosini Monument that symbolises those men, along with the inKatha, the most sacred coil of the Zulu nation. We have also visited the reconstructed kraals that once filled the valley, and the famous Piet Retief memorial. But it was here at Ulundi, on 4th July 1879, that the British Lord Chelmsford had his revenge for the defeats he had suffered – pr perhaps caused – back in January that year. The Zulu regiments were mown down by Gatling guns, three thousand dead in only half an hour, and King Cetshwayo sent into exile in Cape Town. But the British had to bring him back four years later, by which time civil war had broken out. In a second Battle of Ulundi, in 1884, Cetshwayo is mortally wounded and, at his side, hacked to death by some of those he had previously led, was the Zulus’ heroic commander at Isandlwana, Chief Ntshingwayo kaMahole Khosa.

Beyond Ulundi is the start of the enormous Hluhluwe National Park, over sixty miles across. We have the usual adventures – chased by an enraged bull elephant (well, it was the car ahead of us, in truth); stopped by warthogs and their babies blocking the track, etc. And, by the way, if anybody is ever looking for a cheap alternative to a 4×4, I can’t recommend the Toyota Corolla. The Avis Car Hire people would simply not believe the places that we went in their lovely vehicle. I just hope they never look under the chassis! But we eventually cross the umFolosi River and reach the other side, to the Falaza Game Lodge in Hluhluwe itself, near False Bay. We’re here really because the central character in The Kraals of Ulundi comes from this place and, appropriately, tonight we eat dinner in front of a fire pit while, just across from us, the Hluhluwe Community Choir sing and giya for us.

The bus full of French tourists that turns up at the DamaZulu Cultural Village means that Ann and I won’t, as we feared, be alone for this well-known spectacle. We’re greeted by Isaac, the Event Manager, who teaches us a few more isiZulu words and phrases before we start the trip. But we’ve only been there for a few minutes when one of the Frenchmen – improbably called Marcel – catches his sandal and foot on a tree root, managing to take the tip off his little toe. Chaos! The French guides have no first-aid kit and the village healer, the iSanusi, is on holiday today. Bloody typical – never a witch doctor around when you really need one. But it’s the McCalls to the rescue. Out come our antiseptic wipes, our germolene, some dressing and a roll of plaster. I think Marcel probably needs a tetanus jab too but Boots didn’t provide this. Anyway, we mend Marcel in no more than a jiffy and I’m rewarded by being declared an honorary iSanusi for the day. Keith and Nina would be proud of me, I think. Then, on with the entertainment – excellent! In the afternoon we head off on another game drive. More giraffes, naturally, as well as red duiker, impala, wildebeest and water buffalo. Dung beetles too. It’s astonishing to see them flying about – almost as big as a small bird – and one of them gives Ann a nasty whack when it collides with the back of her neck.

At 5.00 in the morning there’s a frog in the shower with me. Then we’re on the road again to see some more wildlife. Not alone, of course. There are Zulu kids in tidy uniforms already walking who knows how far to school; Zulu men and women working in the endless acres of pineapple fields; a Zulu boy taking his goats to pasture. We feel spoiled as, out in the vastness of the National Park, we catch up with zebra, buffalo, kudu, nyala and hippos in the umFolosi. No more elephants though, sadly. The wind is blowing from the south so the elephants, constantly moving with their faces to the wind, have headed that way. Across the river. Beyond our reach. No lions either. But that’s no big deal though. And we get to see a mongoose, hyena and the Marshall’s eagle, amongst lots of other stuff.

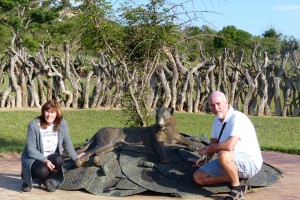

There’s always time for one more trip, isn’t there? And since we haven’t seen any big cats in the wild, we decide to pay a visit to the local Cheetah Rehab Centre – well, it’s something like that!

At midnight, the safari vehicle has left St Lucia far behind and is carrying us through the iSimangaliso Wetlands National Park to reach Cape Vidal. It’s very strange doing game drive at night but,

remarkably, we see plenty of hyena, bush babies, kudu, buffalo, rhino and zebra. Hippos too, of course. They are nocturnal creatures and only really come out of the water during the hours of darkness. And this beautiful estuary area is ideal habitat for them. So we find them lumbering along the road at various points until we finally reach Cape Vidal itself. We wait while Toba, our Zulu guide, softens the tyres, and then it’s off along the beach, following the waves of the Indian Ocean under a star-filled African sky for about 10 kilometres. And there we find the thing we’ve come for – the tracks of an enormous turtle. We walk softly on its trail into the low dunes and find her already hard at work. She’s a Loggerhead and has dug out a bunker, maybe five feet across, in the middle of which is a narrower but much deeper hole – and into that hole she’s depositing batches of shiny white eggs, between 50 and 100 of them. It takes maybe an hour, then another hour as she carefully backfills the bunker, heaving, sighing and resting regularly from the enormous effort, flicking back soft sand with her two front flippers, packing it down with the back ones until the site is invisible. It takes her a further half-hour for her to find her way back into the waves. Astonishing experience. But it’s too late now to do anything except snatch an hour’s sleep before heading down the coast to Ballito’s Lalaria Lodge, arriving there at 8.00am. Far too early to check in, although Caryl Legassick, the owner, doesn’t even query who we are, simply greeting us with, ‘Hi there! You want to sit on the terrace and watch whales and dolphins?’ And we do.

The Seamen’s Mission in Durban is preparing the thousands of gift bags that they prepare every year for those merchant sailors who happen to be in the port and away from their families on Christmas Day. So we help with parcelling up the woolly hats, socks, other little trinkets and hand-made Christmas cards produced by the local school kids. It’s an interesting start to our tour of the city in the company of Karen Lotter, the social media co-ordinator for the Alliance of Independent Authors. She’s taking photos for the Mission’s website but, once that’s done, we drive into the city centre for a whistle-stop tour of the sites before picking up Karen’s two colleagues, Mbusisiwa Zuma and Mabusi Kgwete. Before too long we’re in the south-west suburbs, at Umlazi, the second-largest township in South Africa – Soweto being the biggest. Like all townships, this was constructed to provide barracks accommodation for Durban’s cheap labour pool but is now establishing itself as a distinct community. All the same, there are 1.5 million people here and only around 50,000 with formal work. We eat lunch at a friendly place on the main road into Umlazi while learning about the pros and cons of everyday life in modern post-apartheid South Africa. Then it’s back into Durban for coffee on the North Beach promenade before Karen drops us again at the Moses Mabhida Stadium. And that’s it! We have a final chat with Caryl Leggasick about history, about growing up in colonial Durban with parents from very different backgrounds and perspectives – her father blindly pro-British, her mother imprisoned as a child by the British in a concentration camp during the Second Boer War – and about what the future holds for the country that they now share with the black majority. We swap anecdotes too – about the distances that the Zulus walk to get to work or school; about the patriarchal nature of Zulu society; about the phenomenal loads that Zulu women (it’s always the women!) carry on their heads. But Caryl wins the anecdotes competition hands-down with her tale of recently being at the local shopping mall and seeing the two male store assistants loading nothing less than a washing machine onto a female customer’s head. Tomorrow we make the long flight back to the UK – yet we both know it won’t be too long before we return here.

Cosi, Cosi, Yaphela

Leave a Reply